STUDY. Argentina has been characterised for a long time by inflation, recession, poverty and failed reforms. We analyse the reforms of Javier Milei with the help of the Austrian School of Economics, German ordoliberalism and the theory of financial repression. It is shown that Milei’s reforms have achieved with expenditure cuts and decisive deregulation an impressing consolidation of the public budget, a decline of inflation as well as – with a lag – growth and a falling poverty rate. His reforms may become a blueprint for other countries such as Germany.

1 Argentina before and under Javier Milei

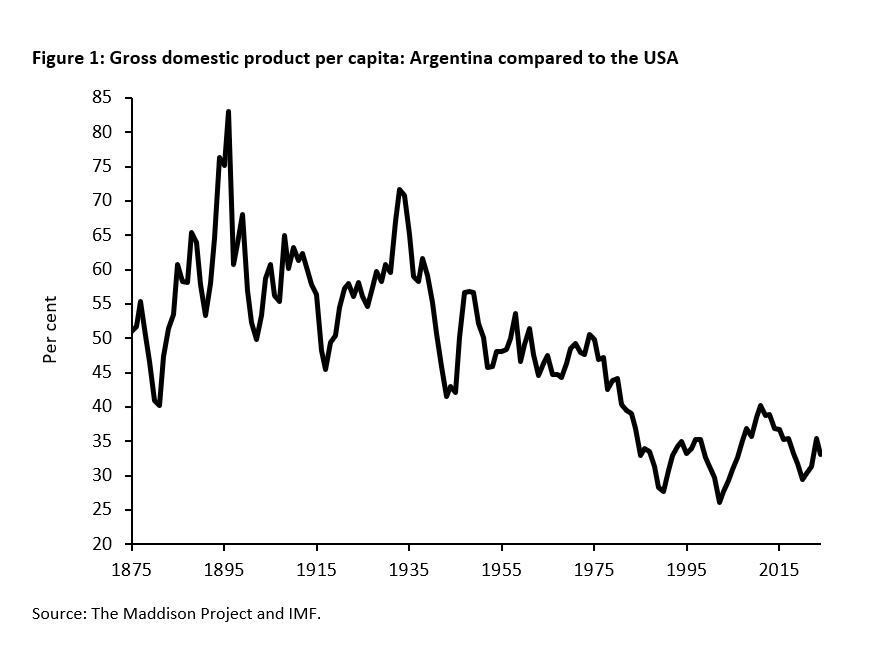

Before the World War I, Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world, with an average per capita income that came close to that of the USA (see Figure 1). The country has fertile agricultural soils, abundant natural resources and a well-educated population. As the economy was traditionally characterised by agriculture, Argentina mainly exported agricultural goods until the 1950s. In 1946, Juan Domingo Perón was elected president, who came to power "as a hero of the working class" by making far-reaching concessions to the trade unions. From then on, the Peronists directed Argentina's development towards an industrialised country, with the trade unions becoming an important pillar of their power.

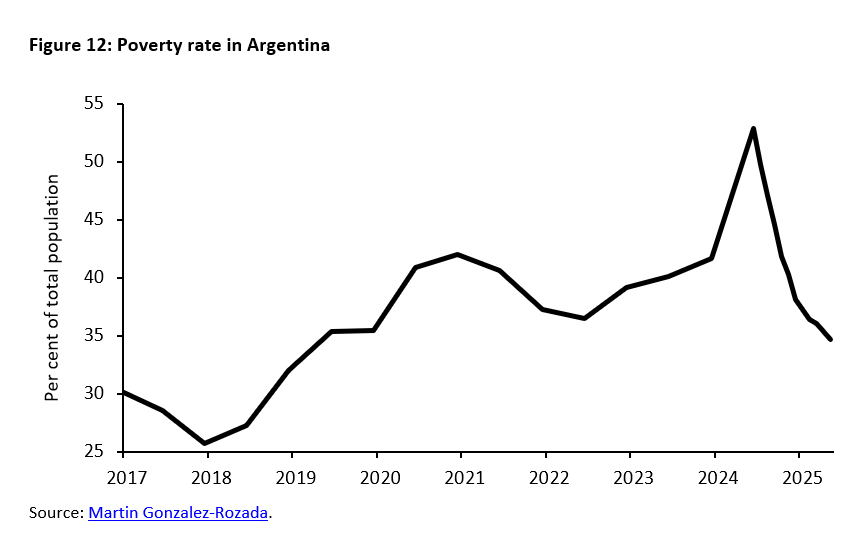

As Milei has introduced extensive reforms, a controversial debate has emerged about the pros and cons. Those in favour argue that fundamental reforms are essential to revive the Argentinian economy (Bagus 2024, Pandiella 2018). The lifting of price controls and the increase in the poverty rate, on the other hand, have been heavily criticised (TAZ 2025).

To evaluate the political approach, we draw on the Austrian School of Economics as represented by Mises (1912, 1949) and Hayek (1944, 1945, 1976), German ordoliberalism as represented by Eucken (1952) and McKinnon's (1993) "Order of Economic Liberalisation". We shed light on Milei's concept of the market, examine the efforts towards macroeconomic stabilisation and provide an overview of the ongoing deregulation process. From this we derive implications for both Argentina and the industrialised countries in general.

2 The role of the economic order

Javier Milei has studied economics and published several books and articles (see e.g. Milei 2018, Milei 2020), from which it is clear that his views are rooted in the Austrian School. This school of thought is particularly concerned with individual freedom, limited role of the state in the economy and society, and monetary stability. Mises (1949) held the view that human action consists of goals and means that develop over time and criticised state intervention in the economy. He considered socialist planned economies to be unviable in the long term, as they disrupt the price mechanism and lead to harmful inefficiencies. One contemporary Argentinian economist who refers to the Austrian school is Benegas Lynch (2023).

Javier Milei has expressed his sympathy for Murray Rothbard as a representative of "anarcho-capitalism" (e.g. Milei 2021). Rothbard (1962) argues that state intervention in the economy is not only unnecessary, but also harmful, as it disrupts the natural self-regulating mechanisms of the market. Rothbard (1982) argued in favour of a society without state, in which all services, including the legal system and security, are provided by the market. In view of the less far-reaching reforms made by previous governments, Javier Milei called for radical liberalisation, which he symbolised with a chainsaw. The implementation of his demand could be the transition from a largely centralised to a market-oriented economic order as described for example by Eucken (1952) in his constitutive principles of a market order.

2.1 Constitutive principles of the competition order according to Eucken (1952)

Eucken (1952) formulated seven constitutive principles of a market order (as an academic basis for the West German currency and economic reform of 1948). The primacy of monetary policy (1) states that only a stable currency gives companies planning security for the future as a foundation for investment and growth. Free prices (2) signalise scarcity and ensure the efficient use of resources. Open markets (3) allow all companies to enter the market, so that competition can lead to greater efficiency, low prices and innovation. Private ownership (4) ensures that companies strive for profit and therefore utilise resources efficiently.

Freedom of contract (5) allows companies to adapt contracts to their individual situation within a given legal framework. The principle of liability (6) ensures that entrepreneurs can privatise profits but must also bear losses themselves. Economic policy interventions should be restrained (7) so that the state does not crowd out private economic activity. Economic conditions should not be changed by ever new interventions by the state (consistency in economic policy). "The economy is not a patient that can be operated on without interruption", said Ludwig Erhard, historically the most important political advocate of the market economy in West Germany (see Erhard 1957).

According to Eucken (1952), all seven principles had to be fulfilled together in order to achieve a positive effect on growth. When the market-oriented reforms together with the freedom-oriented Basic Law implemented these principles in many areas of the West German economy, an economic miracle was created that made Germany the growth engine of Western Europe and thus also stabilised it politically (Schnabl 2023).

2.2 Milei's view of the economic order

The political alliance "La Libertad Avanza", founded in 2021 and led by Javier Milei, advocates free markets without state intervention, free competition, division of labour and social cooperation. It favours efficiency, meritocracy and transparent management of public funds (La Libertad Avanza 2023). It is based on liberal principles such as respect for individual lifestyles, the principle of non-aggression and the defence of the fundamental rights to life, liberty and private property.

(1) The primacy of monetary policy by Eucken (1952) is represented by the demand for the abolition of the central bank and competition between currencies to allow citizens to freely choose their monetary system, with the population possibly opting for dollarisation. (2) The abolition of price and rent controls, foreign exchange controls and the restriction of the power of trade unions is in line with the principle of free prices. (3) Markets are to be opened up by privatising loss-making public companies and promoting private investment. The abolition of export and import duties and the lifting of foreign exchange controls shall promote competition in Argentina.

The government is creating more incentives for private economic activity through tax cuts, which shall be offset by spending cuts. The planned radical downsizing of the state and deregulation in Argentina shall promote private property (4), freedom of contract (5) and the principle of liability (6). The deregulation of the banking system and the abolition of foreign exchange restrictions are important building blocks for the liberalisation of the financial market, which according to McKinnon (1993) represents an important step towards more freedom of contract. The intended cancellation of unproductive government spending and the downsizing of the state are in line with Eucken's (1952) constancy in economic policy making (7).

The "Pacto de Mayo" of May 2024 prompted all governors of the Argentine provinces to sign a 10-point plan to rebuild the Argentine economy, which can be seen as a new edition of the so-called Washington Consensus (Williamson 2000) for Argentina. The 10 points (Buenos Aires Times 2024) include (1) the inviolability of private property, (2) a debt brake, (3) the reduction of government spending to 25 per cent of gross domestic product, (4) the reduction of the tax burden, (5) the renegotiation of the fiscal equalisation with Argentina's provinces, (6) the obligation of the provinces to extract raw materials, (7) a labour market reform, (8) a pension reform, (9) an administrative reform and (10) the liberalisation of Argentina's foreign trade.

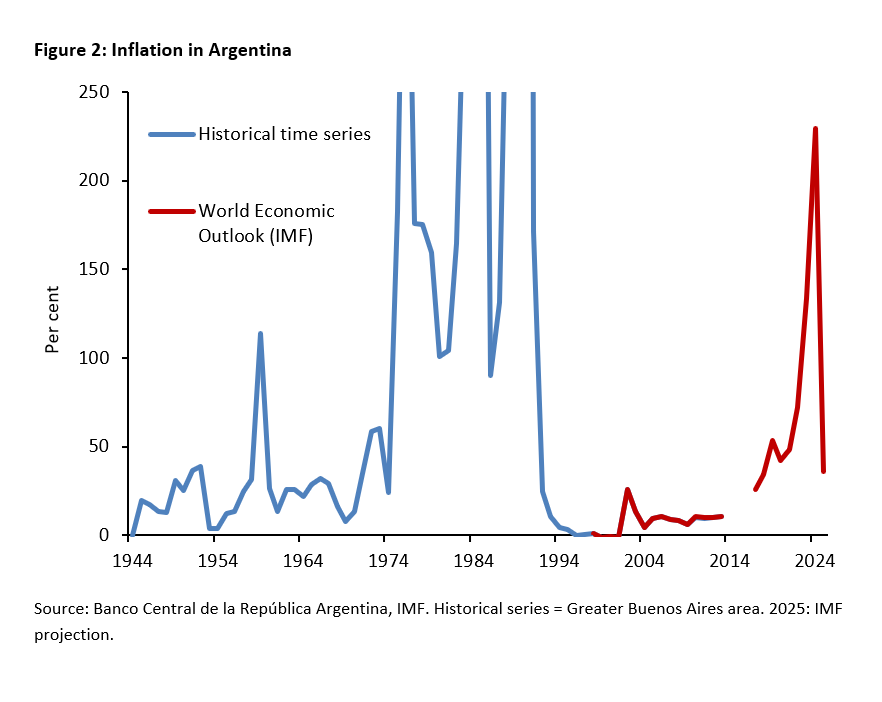

3 Fiscal and monetary consolidation

Figure 2 shows above all high and strongly fluctuating inflation rates, which not only kept growth low in the past, but also had unfair distributional effects. One part of the population - above all the Peronist supporters - benefited from a large public sector and subsidies for state-owned companies, as these provided a reliable source of income. The other part of the population, on the other hand, suffered from high inflation and low real incomes. High inflation helped to keep real public debt under control at the expense of consumers and savers. Foreign exchange controls were a tax on farmers and hindered the protection of savings through the exchange of pesos into US dollars.

Hayek (1976) emphasised that the central bank's dependence on the government (and/or the financial sector) leads to inflation, which is a major obstacle to growth. Hayek (1976) therefore proposed the abolition of central banks and competition between private currency issuers. Rothbard (1962, 1982) rejected central banks and favoured gold as a monetary base to prevent inflation. Huerta de Soto (2009) argued that a banking system influenced by central banks is inherently unstable and thus systematically causes economic crises. He proposed backing currencies with gold (gold standard to create a stable and crisis-proof market economy.

As the liberalisation of the financial markets in conjunction with a persistently loose monetary policy leads to exuberance on the financial markets as a precursor to crisis, McKinnon (1993) saw fiscal and monetary control as a prerequisite for the dismantling of regulations on financial and goods markets. To take the pressure off the central bank to buy government bonds, McKinnon (1993) defined the consolidation of government finances, including the abolition of extra-budgetary government spending that escapes parliamentary control, as a prerequisite for the central bank's ability to keep prices stable.

3.1 Fiscal stabilisation under Milei

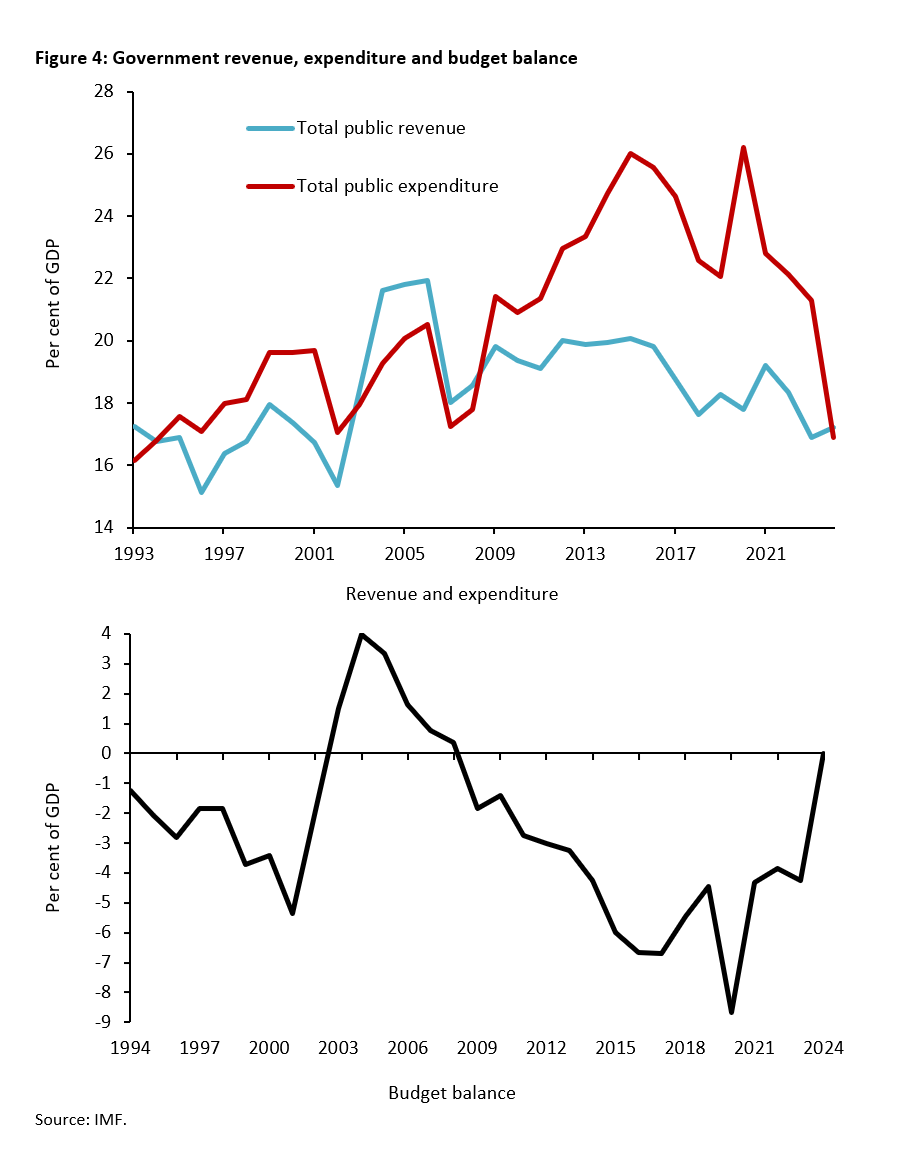

After taking office in December 2023, Milei announced a shock therapy, i.e. rapid and comprehensive reforms instead of a gradual approach (see Hall 2023). According to Milei, budget consolidation through tax increases is not the same as through spending cuts. The focus of his tax reform was therefore aimed at reducing spending rather than increasing taxes (The Economist 2024), implying the need for sharp spending cuts to consolidate the budget. In order to reduce government spending, especially transfers to the provinces, spending on public works and public sector employment was reduced (Sturzenegger 2025). Social transfers were essentially maintained, but the administration of social programmes was streamlined (The Economist 2024).

The number of ministries was halved and over 40,000 civil service jobs were cut (Bagus 2025). State subsidies for electricity, gas and public transport, among others, were cut. Public institutions in the areas of education, science and health had to accept massive cuts to their budgets. Federal payments to the provinces were frozen. In addition to the nominal spending cuts, payments to civil servants, pensioners and welfare recipients were not fully adjusted for inflation (World Bank Group 2024). According to Milei, public spending was cut by a third in 2024 (The Economist 2024, see Figure 4).

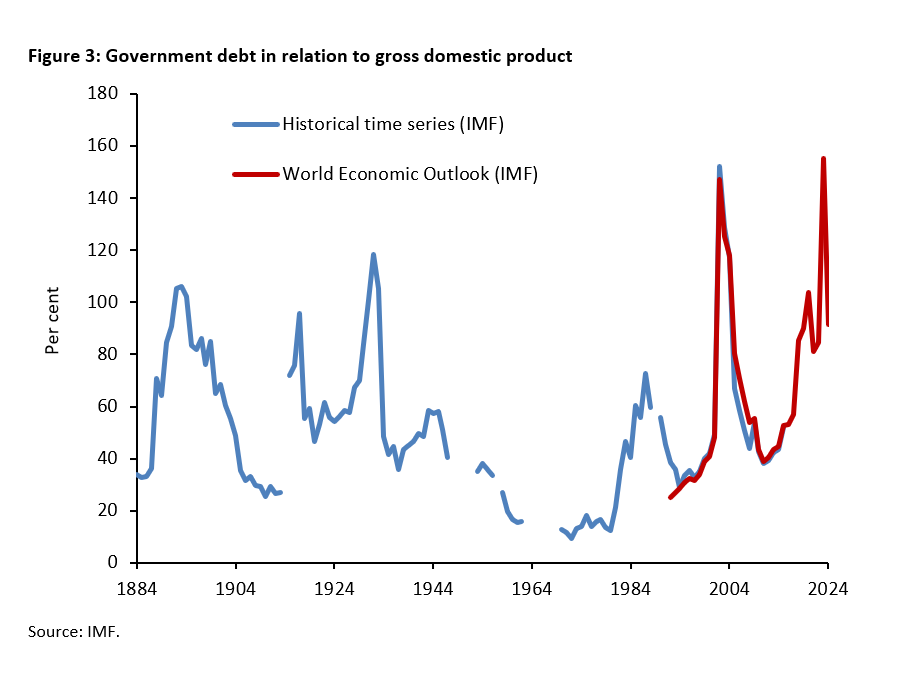

The national budget has had a high deficit since 2009, reaching a peak of almost 9 per cent of GDP in 2020 (see Figure 4). In view of sharply declining expenditure, the Argentinian government was able to announce a budget surplus for 2024 for the first time in 15 years (see Figure 4) amounting to USD 1.6 billion (Reuters 2025a). In December 2024, Milei announced a tax reform aimed at simplifying the tax system by abolishing 90 per cent of all taxes. The Argentinian provinces are to be allowed to levy their own taxes, which means tax competition between the provinces (Buenos Aires Herald 2024). The government temporarily increased the tax on the purchase of foreign currency for imports but then reduced it and finally abolished it at the end of 2024.

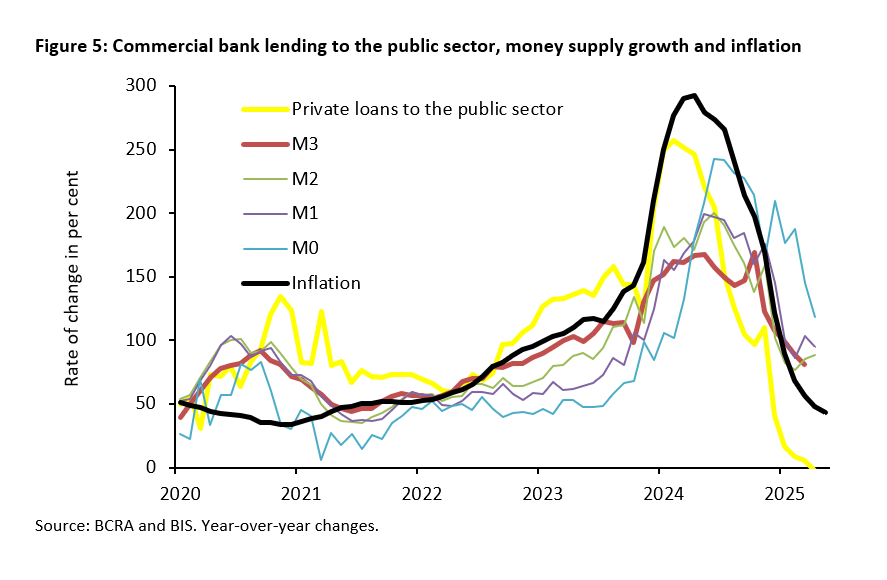

In Argentina, government spending was the main driver of inflation. In a state-controlled banking system, when banks lend to the government to finance government spending, monetary aggregates such as M1 and M2 increase. Uncontrolled government spending ultimately drives both money creation and inflation. This appears to have been the case in Argentina, where a strong correlation can be observed between commercial bank credit growth to the public sector, money supply growth and inflation (see Sturzenegger (2025) and Figure 5).

Thus, cutting government spending and thus commercial bank lending to the public sector was a key measure to curb inflation. As the budget deficit was consolidated, inflation began to fall. After peaking at 290% in April 2024, inflation continued to fall, reaching 43.5% in May 2025 (see Figure 5).

3.2 Monetary stabilisation under Milei

The credibility of a currency depends heavily on the solidity of the central bank's balance sheet. In the past, the Argentine central bank has made a significant contribution to financing government spending by directly purchasing government bonds or assuming (future) government financing obligations. When Milei took office in December 2023, the Banco Central de la República Argentina (BCRA) had four major burdens, which would have further undermined the credibility of the peso if they had remained in place.

Firstly, the central bank held large amounts of Argentine government bonds (in pesos and dollars), the value of which was uncertain due to the government's unsound budgetary situation. Secondly, the BCRA had high liabilities in the form of outstanding central bank bonds (LELIQs), which served to absorb excess liquidity from the markets. These implied high interest obligations, which were a major reason for the central bank's losses in 2023. The resulting high deficit of the BCRA represented an additional deficit to the government's budget deficit.

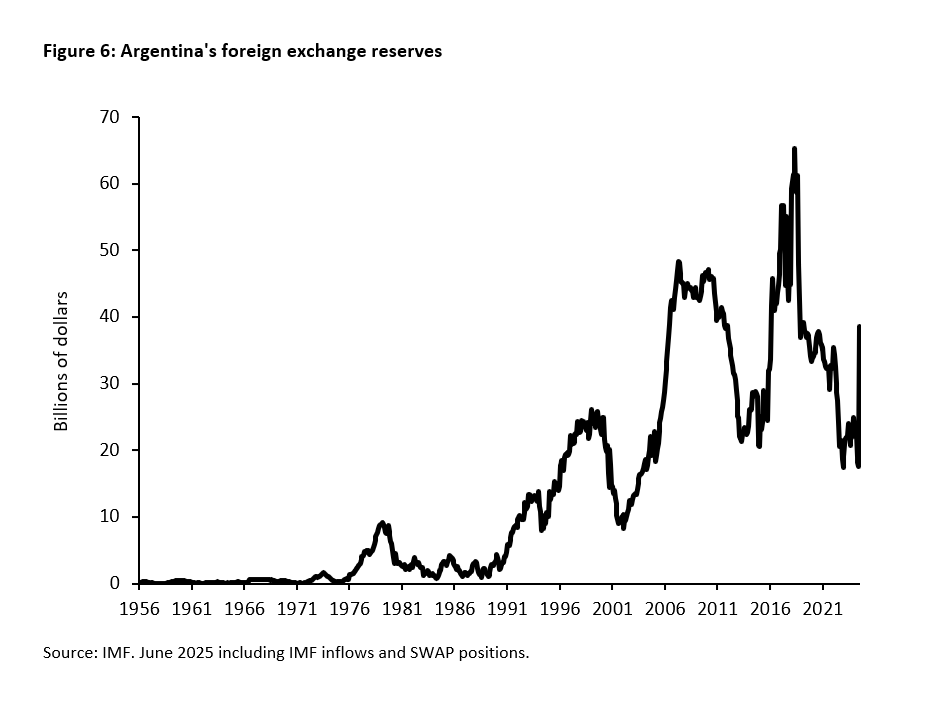

Third, Argentina's foreign exchange reserves had fallen sharply before Milei took office, as shown in Figure 6. With off-balance sheet debt in the form of financing obligations to importers of up to USD 50bn (Rallo 2024), BCRA's net foreign currency liabilities were estimated at around USD 11bn. In addition, the peso bonds issued by the government with the right to be redeemed at the central bank at any time (equivalent to around USD 20 billion) represented an additional hidden liability for the central bank (Ring 2024).

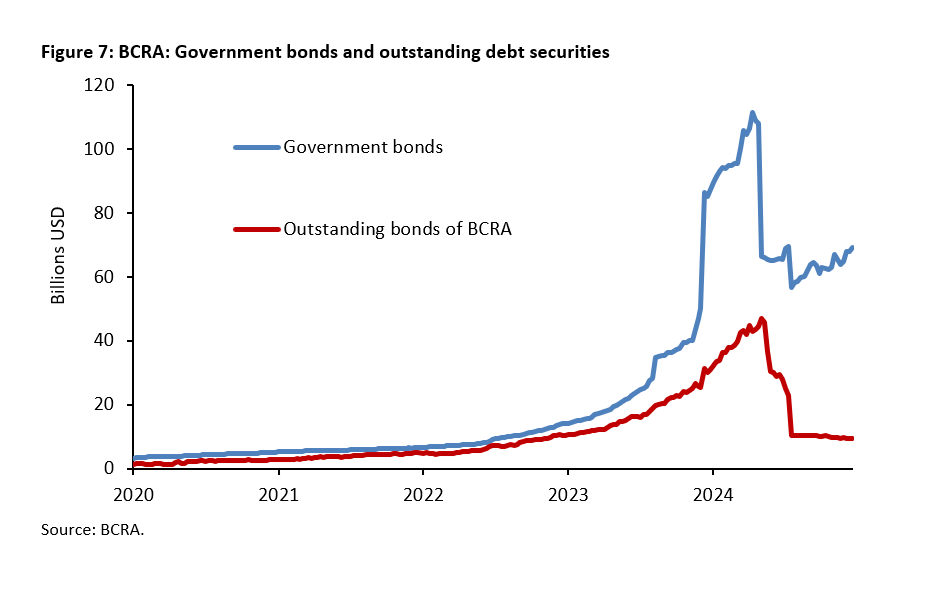

Four important steps were taken to stabilise the central bank and thus the currency. Firstly, pressure was taken off the central bank to buy government bonds by cutting government spending and turning the budget balance positive (as shown above). As a result, the central bank's holdings of government bonds, which had continued to rise during 2023, were reduced over 2024. At the end of 2024, the stock totalled USD 68 billion compared to USD 111 billion in April 2024 (see Figure 7). Secondly, the government reduced the BCRA's outstanding central bank bonds, which had led to a high and uncontrolled interest burden for the BCRA. The volume of outstanding central bank bonds was reduced from USD 46 billion in May 2024 to less than USD 10 billion by the end of 2024 with the help of government surpluses (see Figure 7).

Thirdly, the hidden liabilities of the BCRA have been eliminated. The peso government bonds with the right of redemption at the central bank (puts) were decoupled from the right of redemption at the central bank with a corresponding compensation for the banks (Ring 2024). In addition, the central bank issued new bonds (Bond for the Reconstruction of a Free Argentina) to fulfil its dollar obligations to importers, thereby transferring the hidden debt to the regular financial framework. The central bank debt were then partially reduced with the help of the government surpluses generated.

Although inflation has fallen sharply, the crucial question remains as to how the Banco Central de la República Argentina can be shielded from the influence of politics in the long term. An independent central bank would be a long-term commitment to budgetary discipline, as the state would be deprived of the possibility of financing itself via the central bank. However, the independence of the central bank can be politically undermined at any time. This is likely to happen in the future, especially in Argentina, where inflation has been entrenched in politics and society for decades.

A tight exchange rate peg to the dollar would limit the decision-making power of the central monetary authority, as was the case with the currency board in the 1990s. In contrast to a simple fixed exchange rate system, only parliament can loosen the tight peg to the dollar in a currency board. In January 2002, however, the currency board in Argentina collapsed. One of the reasons for this was that, unlike a currency board in the narrower sense, the monetary base was not 100 % covered by foreign exchange reserves (Hanke 2008). In addition, persistent government deficits and inflation had undermined the international competitiveness of Argentina's export sector.

Dollarisation, which Milei repeatedly called for during the election campaign, would therefore be the safest way to achieve lasting currency stability (Cachanosky 2024). If the central bank is abolished, it can no longer be abused by future governments, which corresponds to Hayek's (1976) idea of the "denationalisation of money". In Argentina, the population already holds considerable amounts of dollars due to persistently high inflation, which would facilitate dollarisation. In Ecuador, the population is largely in favour of its dollarisation and keen to maintain it (Cachanosky et al. 2023). However, dollarisation is not (yet) on the political agenda.

4 Deregulation

According to McKinnon (1993), the third step of an economic liberalisation process is the deregulation of national and international goods, labour and capital markets. The liberalisation of the goods market creates competition between companies. Less regulated labour markets reduce labour costs for companies and the state. The banking system should be freed from high minimum reserve requirements and interest rate regulations, because only on free capital markets do depositors receive positive real interest rates as a prerequisite for efficient capital allocation. Market-determined, risk-adequate interest rates force companies to adapt to market conditions. Following the liberalisation of domestic markets, McKinnon (1993) recommends the liberalisation of international flows of goods and capital, including foreign exchange transactions. The liberalisation of trade should take place earlier than the liberalisation of capital flows.2

4.1 Deregulation of the domestic markets

At the beginning of 2024, Milei aimed to amend or abolish a total of more than 350 laws in the areas of tenancy and labour law, the pension system and the financial system. The Senate approved the reform package in June 2024. The "Law of Bases and Starting Points for the Freedom of Argentines" (Ley Bases) of July 2024 formed the legal basis for a comprehensive deregulation programme. The establishment of the Ministry of Deregulation and State Transformation under the leadership of Frederico Sturzenegger, which has the power to repeal, amend and implement decrees without them having to be passed by parliament, forms the institutional framework (Bagus 2025). The aim is deregulation, reforms and modernisation of the state in order to reduce public spending and improve its efficiency and effectiveness (Boletin Oficial Republica Argentina 2024). According to Milei (2025), 3.5 regulations per day were abolished at times.

The first and most important step was the abolition of price controls, for example for basic commodities such as milk, sugar and cooking gas (Dubé 2024a). The abolition of rent controls was a great success. Immediately after the liberalisation, rents for flats in Buenos Aires initially rose dramatically. As a result, many previously vacant flats were put on the market. It is estimated that more than 200,000 residential units were withheld from the market due to the rent controls. As a result of the new supply, rents quickly fell back below the 2022 level (Dubé 2024b).

State-owned companies were privatised, e.g. the airline Aerolineas Argentinas and the energy company Enarsa. Milei has facilitated access to the aviation market, which has increased the number of airlines. The requirement that public sector employees book their flights with the state airline or that other airlines are not allowed to park their aircraft overnight at one of the main airports in Buenos Aires was abolished (Vásquez 2024). A new legal framework was created in the energy sector to promote private investment and competition.

The law aims to make the labour market more flexible to promote employment. The collectively agreed severance scheme can be replaced by a severance fund financed by employers to reduce costs for companies. In future, large companies will be able to hire employees for a six-month probationary period. Self-employed persons will be able to employ three people without a formal employment relationship (GTAI 2024). Active participation in certain protests is now considered a "serious labour law violation" (grave injuria laboral), which weakens the negotiating position of the influential trade unions.

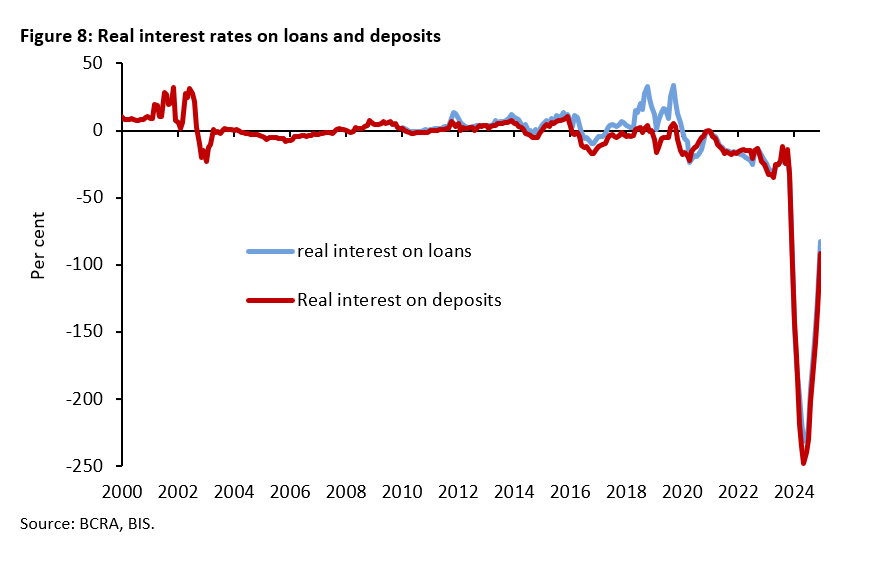

In February 2025, the government converted the largest state-owned bank, Banco de la Nación Argentina, into a public limited company by presidential decree (Reuters 2025b). Although the state still holds 99% of the shares, this step signals a future privatisation. This can be seen as an important prerequisite for the commercial banks in Argentina to be able to freely set interest rates and grant loans. The successful elimination of inflation is an important precondition for efficient lending, as this enables positive real interest rates. This process is progressing without positive real interest rates having been achieved to date (see Figure 8).

In February 2025, commercial banks were authorised to grant dollar loans to all companies (Bagus 2025). This is an important step towards creating a functioning dollar credit market that reflects the high degree of dollarisation of the economy. While the lifting of price ceilings leads to price increases, deregulation contributes to falling prices as costs for companies are reduced and competition increases. Sturzenegger (2025), Argentinian Minister of Deregulation and State Transformation, has argued that, as a rule of thumb, deregulation of certain sectors leads to a price decrease of around 30 per cent.

4.2 Elimination of customs duties, exchange controls and capital controls

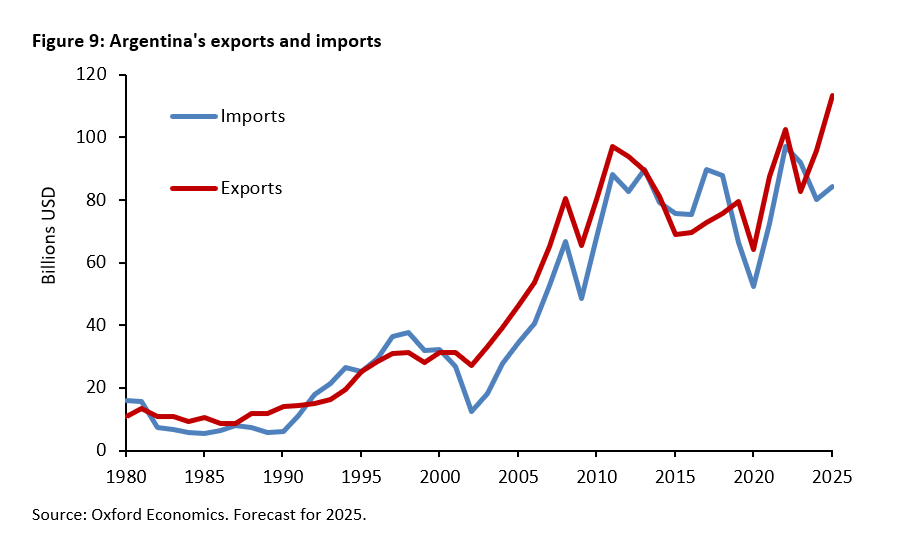

The liberalisation of international trade began in 2024 (Nugent 2025). The government lowered customs duties on many products (without abolishing them completely) and reduced the bureaucratic burden on the Argentinian customs authority. The requirement for domestic manufacturers to give authorisation for certain imports was abolished. The president lifted export controls on beef and abolished the authorisation requirement for steel imports (in the hope of reducing construction costs) (Dubé 2024a). The reduction of trade restrictions was accompanied by an increase in exports (see Figure 9) and thus contributed to an improvement in the trade balance.

Before Milei, there were several exchange rates. The dollar revenues of exporters (especially farmers) had to be paid to the government, which levied an export tax (retenciones) on them. The remaining revenue was converted into pesos at an exchange rate set by the government, which was below the black-market rate. This meant an additional (indirect) tax on agricultural products, which represent an important source of international income for Argentina. If farmers wanted to invest the remaining proceeds in dollars to protect them from inflation, they had to buy dollars at a much less favourable exchange rate. By heavily taxing exports, the government reduced the incentive to produce and export agricultural products that are competitive on the international market.

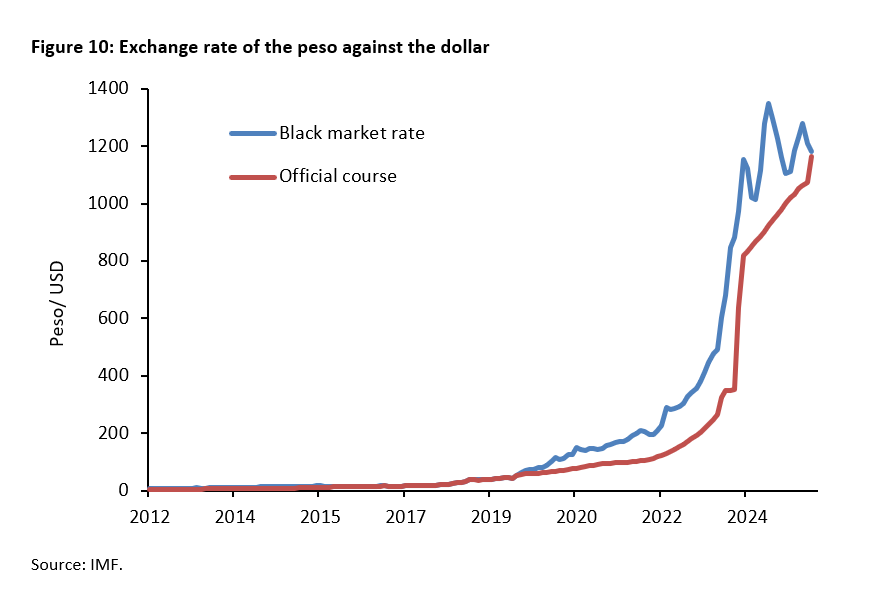

To promote exports, foreign exchange and exchange rate controls were gradually lifted in 2024. In December 2023, the peso was officially devalued to (partially) eliminate the difference between the official exchange rate set by the government and the black-market rate of the dollar (blue dollar) (see Figure 10). As a result, the official exchange rate and the black-market rate have converged and the peso has stabilised against the dollar. This reduced the incentive for foreign exchange black market transactions and facilitated international transactions.

Since January 2024, the peso has been allowed to depreciate by 2 per cent per month, which has meant a real appreciation of the peso against the dollar at a much higher inflation rate. As inflation weakened over the course of 2024, the central bank reduced the monthly devaluation to 1 per cent from February 2025 (Reuters 2025c). In December 2024, the PAIS tax (Impuesto Para una Argentina Inlcusiva y Solidaria) on foreign currency purchases was abolished.

The government began to dismantle the extensive capital controls (cepo). It abolished the long waiting periods for international payments at the beginning of 2024. It tripled the amount Argentinians are allowed to order from abroad for personal use to 3,000 dollars and exempted the first 400 dollars from customs duties. The flat tax of 7.5 per cent on all imported goods and the 30 per cent tax on card purchases abroad were abolished in December 2024. Increasing international competition is putting pressure on the domestic industry to reduce costs and prices. It also increases the pressure on the government to reduce regulatory barriers for domestic companies.

On 12 April 2024, the government abolished almost all capital controls for private individuals and partially for companies (Lexlink 2025).3 The central bank allows the exchange rate of the peso to fluctuate freely between 1,000 and 1,400 pesos per dollar. The IMF has flanked this measure with a loan of 20 billion dollars, making the central bank's interventions more credible. These steps can be seen as an end to decades of import substitution policies. The complete liberalisation of international capital flows removes the distortions between banks that have access to dollar assets and those that do not.

The "Incentive Regime for Large Investments" (RIGI) was created to attract domestic and foreign investment through tax concessions and other incentives. It applies to investments in the forestry, industry, tourism, infrastructure, mining, technology, steel, energy, oil and gas sectors. It promises tax, customs, foreign exchange and regulatory exemptions for 30 years. To be eligible for the RIGI programme, an investment project must be worth at least 200 million dollars. At least 40 per cent of the investment must be made within two years of the investment project being approved. Each project must allocate at least 20 per cent of the total investment to local suppliers, provided they are available and meet market conditions in terms of price and quality (Etchebarne et al. 2024).

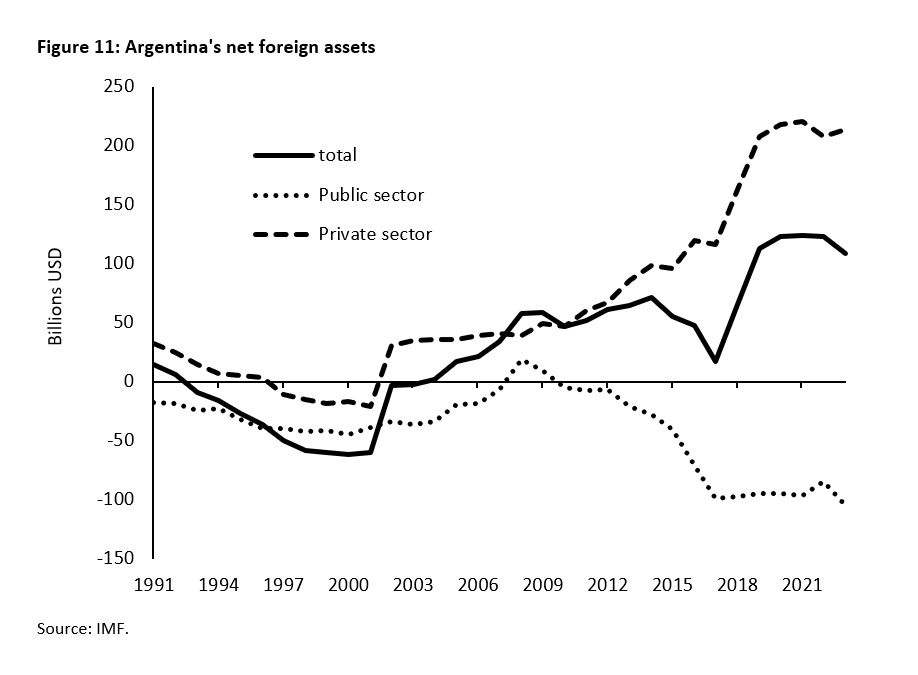

A key question is whether the liberalisation of international capital flows will be able to restore international confidence in Argentina as a debtor. To date, Argentina has been cut off from the international capital markets as it has defaulted on international debt several times in the past. This has made Argentina dependent on loans from the IMF. While the Argentine government is an international debtor, the private sector holds significant assets abroad (Raisbeck 2025), signalling the Argentine population's distrust of the government. Overall, Argentina's net international investment position is positive (Figure 11). If the macroeconomic stabilisation process succeeds in regaining the confidence of the Argentine population, the repatriation of foreign assets would significantly strengthen the peso and the domestic economy.

5 Implications for Argentina and other countries

While Javier Milei's radical reform ideas initially met with strong domestic resistance and international criticism, signs of success - namely a balanced budget, declining inflation, the stabilisation of the peso and now also a falling poverty rate - have contributed to the unconventional reform agenda being increasingly respected. Despite the painful measures, Milei has retained the support of the majority of the population. Milei claims to have implemented eight times more reforms in one year than President Menem did in ten years (The Economist 2024). In contrast to President Macri, he has succeeded in balancing the budget and reducing inflation (see also Sturzenegger 2019). The reforms can be seen as an attempt to restructure the Argentinian economy towards agricultural products and the extraction of natural resources, i.e. the country's comparative cost advantages.

In the initial phase, the reforms were criticised for being accompanied by a sharp rise in the poverty rate. However, the positive results materialised with a delay (J-curve effect). While real growth in Argentina was -1.8 per cent in 2024, the IMF is forecasting +5.4 per cent in 2024 and +4.5 per cent in 2025. As the economy is growing again - and inflation in particular is falling - the poverty rate has fallen below the pre-reform level (see Figure 12). The IMF (2025) forecasts a sharp decline in inflation for 2025 and writes: "A major course correction subsequently undertaken by the Milei government-notably a sharp fiscal consolidation, an upfront devaluation, and an end to monetary financing of the budget helped Argentina avert a fullblown crisis and make important strides toward macroeconomic stabilisation."

It has been argued that Milei is dependent on foreign support for its reforms. But in contrast, Milei now seems to be becoming a role model for reforms in other countries. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Milei gave an impassioned speech in favour of the market economy and warned of the dangers of collectivism (World Economic Forum 2024). He emphasised that the prosperity of the Western world was based on freedom and individualism, while collectivist and socialist ideas had increasingly gained the upper hand in the political discourse of Western democracies.

Public debt in industrialised countries has risen sharply and financial repression serves as an instrument to keep the public debt burden sustainable. The significant expansion of regulation and employment in the public sector has helped to stabilise the power of established political parties, while the negative growth and distributional effects associated with monetary and fiscal expansion have been accompanied by growing political polarisation.

In the past, reforms in West Germany (1948/1949) and the United Kingdom (under Margret Thatcher), among others, have revitalised growth and shown that reforms can be successful (Mayer and Schnabl 2022). In the US, the new President Donald Trump has initiated spending cuts and far-reaching deregulation, but a significant reduction in the budget deficit appears to have failed. From this perspective, Argentina under Javier Milei can be seen as a pioneer, although the liberalisation of international capital mobility has not yet been completed and the domestic financial market liberalisation seems to be lagging behind.

References

Bagus, Philipp (2024): Die Ära Milei: Argentiniens neuer Weg. LangenMüller, Stuttgart.

Bagus, Philipp (2025): A 3D Look at Argentina: Deregulation, Deflation, Dollarization. The Economists’ Voice Online First.

Benegas Lynch, Alberto (2023): Los Aparates Estatales nos Aplastan. Fundación Libertad, Buenos Aires.

Boletin Oficial Republica Argentina (2024): Poder Ejecutivo – Decreto 585/2024. URL: www.boletinoficial.gov.ar/detalleAviso/primera/310123/20240705. (publiziert: 4.7.2024, letzter Zugang: 6.3.205).

Buenos Aires Herald (2024) Milei’s 2025 Promises: Less Taxes, No Cepo, and Dollar Transactions for Everything,. URL: buenosairesherald.com/politics/mileis-2025-promises-less-taxes-no-cepo-and-dollar-transactions-for-everything, (publiziert 11.12.2024, letzter Zugang: 3.2.2025).

Buenos Aires Times (2024): Sign Up to My Reforms or Face “Conflict”, President Milei Tells Argentina´s Lawmakers URL: www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/sign-up-to-my-reforms-or-face-conflict-president-milei-tells-argentinas-lawmakers.phtml (publiziert: 1.3.2024, letzter Zugang 1.7.2024).

Cachanosky, Nicolas (2024): Dollarisation in Argentina: A Missed Opportunity. American Institute of Enterprise Research. URL: www.aier.org/article/dollarization-in-argentina-a-missed-opportunity/ (publiziert: 13.2.2024, letzter Zugang: 7.5.2024).

Cachanosky, Nicolas / Ocampo, Emilio / Salter, Alexander (2021): Lessons from Latin America Dollarisation in the Twenty First Century. The Economists' Voice 1, 2023, 25-42.

Cherif, Reda / Hasanov, Fuad (2024): The Pitfalls of Protectionism: Import Substitution vs. Export-Oriented Industrial Policy. IMF Working Paper 2024/086.

Dubé (2024a): Argentina Passes Slimmed-Down Economic Reforms Amid Pain and Protests. The Wall Street Journal. URL: www.wsj.com/world/americas/argentina-passes-slimmed-down-economic-reforms-amid-pain-and-protests-aa89d39b (publiziert: 13.6.2024, letzter Zugang: 4.3.2025).

Dubé (2024b): Argentina Scrapped Its Rent Controls. Now the Market Is Thriving. The Wall Street Journal. URL: www.wsj.com/world/americas/argentina-milei-rent-control-free-market-5345c3d5 (publiziert: 24.9.2024, letzter Zugang 5.3.2025).

Etchebarne, Marcelo / Mancinelli, Augusto / Rubio, Alberto / Fabio, Florencia / Labarile, María / De Berti, Carla (2024): Argentina Enacts its Bases Law and Tax Measures Law: Top Points. DLA Piper. URL: www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/2024/07/argentina-enacts-its-bases-law-and-tax-measures-law (publiziert: 28.6.2024, letzter Zugang: 24.2.2025).

Eucken, Walter (1952): Principles of Economic Policy. Mohr, Tübingen.

Erhard, Ludwig (1957): Prosperity for All. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf.

Fontevecchia, Augustino (2022): Global Stagflation and Massive Debt Crisis – The “Argentinization” of the World Economy. Forbes. URL: www.forbes.com/sites/afontevecchia/2022/08/01/global-stagflation--massive-debt-crises-the-argentinization-of-the-world-economy/ (publiziert: 1.8.2022, letzter Zugang: 12.7.2024).

German Trade & Invest GTAI (2024): Argentiniens Wirtschaftsreform vom Senat angenommen. URL: www.gtai.de/de/trade/argentinien/recht/argentiniens-wirtschaftsreform-vom-senat-angenommen-1787680 (publiziert: 18.6.2024, letzter Zugang: 11.2.2025).

Hall, Katarina (2023): Milei Begins Shock Therapy in Argentina. reason. URL: reason.com/2023/12/15/milei-begins-shock-therapy-in-argentina/ (publiziert: 15.12.2023, letzter Zugang: 1.7.2024).

Hanke, Steve (2008): Why Did Argentina Not Have a Currency Board. Quarterly Journal of Central Banking 18, 3, 56-58.

Hayek, Friedrich August von (1944/ 2003): The Road to Serfdom. Olzog, Munich.

Hayek, Friedrich August von (1945): The Use of Knowledge in the Society. American Economic Review, 25,4, 519-530.

Hayek, Friedrich August von (1968): Wettbewerb als Entdeckungsverfahren, In: Freiburger Studien, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, 249-265.

Hayek, Friedrich August von (1976/2011): The Denationalisation of Money. Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen.

Huerta de Soto, Jesús (2009): Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles. Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn, Alabama.

Internationaler Währungsfonds IWF (2025): IMF Executive Board Discusses the Ex-Post Evaluation of Argentina’s Exceptional Access Under the 2022 Extended Fund Facility, 10.1.2025.

La Libertad Avanza (2023): Plataforma Electoral Nacional. URL: www.electoral.gob.ar/nuevo/paginas/pdf/plataformas/2023/PASO/JUJUY%2079%20PARTIDO%20RENOVADOR%20FEDERAL%20-PLATAFORMA%20LA%20LIBERTAD%20AVANZA.pdf (publiziert: 19.6.2023, letzter Zugang: 27.5.2024).

Lexlink 2025: Argentina: The End of the CEPO? Spoiler Alert: Not Yet. URL: https://lexlink.org/argentina-the-end-of-the-cepo-spoiler-alert-not-yet/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (publiziert: 21.4.2025, letzter Zugang: 12.6.2025).

Marti, Werner (2021): Carlos Menem – gescheiterter wirtschaftlicher Reformer und schillernder Politiker. NZZ. URL: www.nzz.ch/international/nachruf-carlos-menem-argentiniens-gescheiterter-reformer-ld.1538674 (publiziert: 14.2.2021, letzter Zugang: 3.2.2024).

Mayer, Thomas / Schnabl, Gunther (2022): How to Escape from the Debt Trap. Lessons from the Past. The World Economy 46, 4, 991-1016.

McKinnon, Ronald (1973) Money and Capital in Economic Development. The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

McKinnon, Ronald (1993): The Order of Economic Liberalisation. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

Milei, Javier (2018): Desenmascarando la mentira Keynesiana. Unión Editorial, Madrid.

Milei, Javier (2020): Pandenomics: La Economía que Viene en Tiempos de Megarrecesión, Inflación y Crisis Global. Galerina, Buenos Aires.

Milei, Javier (2021): Los distintos tipos de libertarios.YouTubeURL: www.youtube.com/shorts/USSpEjbMCbs(publiziert: 1.8.2021, letzter Zugang: 7.5.2024).

Milei, Javier (2025): El retorno al sendero del crecimiento. La Nacíon.URL: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/opinion-el-retorno-al-sendero-del-crecimiento-nid03012025/ (publiziert: 3.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 7.3.2025).

Mises, Ludwig von Mises (1912/ 2010): Socialism. Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn, Alabama.

Mises, Ludwig von Mises (1949/ 2009): Human Action. Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn, Alabama.

Nugent, Ciara (2025): Javier Milei’s Next Economic Mission: Affordable Air Fryers. Financial Times. URL: www.ft.com/content/e3a9b2ee-c5f4-480a-9ae4-70d94492d57b (publiziert: 7.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 10.1.2025).

Pandiella, Alberto González (2018) Structural Reforms to Boost Growth and Living Standards in Argentina. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1463.

Prebisch, Raul (1950): The Development in Latin America and its Principal Problem. United Nations, New York.

Rallo, Juan Ramon (2024): 100 días de Milei: Luces y Sombras. YouTube. URL: www.youtube.com/watch (publiziert: 20.3.2024, letzter Zugang: 9.5.2024).

Raisbeck, Daniel (2025): Milei’s Key Pending Task: Ending Argentina’s Currency Controls (Part II). Cato Blog. URL: www.cato.org/blog/mileis-key-pending-task-ending-argentinas-currency-controls-part-ii (publiziert: 10.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 20.2.2025).

Reuters (2025a): Milei's Argentina Seals Budget Surplus for First Time in 14 Years. URL: www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-logs-first-financial-surplus-14-years-2024-2025-01-17/ (publiziert: 17.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 5.3.2025).

Reuters (2025b): Gobierno Argentino Convierte a Gigante Banco Nación en Sociedad Anónima Para Mejorar Gestion. URL: www.reuters.com/latam/negocio/R5JRBPM57ZPQFKHTL65OTS2DYA-2025-02-20/ (publiziert: 20.2.2025, letzter Zugang: 5.3.2025).

Reuters (2025c): Argentina Slows Peso Crawling Peg as Inflation Eases. URL: www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-inflation-ticks-up-27-december-ends-2024-1178-2025-01-14/ (publiziert: 14.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 5.3.2025).

Ring, Stephan (2024): Argentiniens Weg zurück. Javier Mileis Stabilisierende Geldpolitik. Ludwig von Mises Institut Deutschland. URL: www.misesde.org/2024/08/argentiniens-weg-zurueck-javier-mileis-stabilisierende-geldpolitik (publiziert: 3.8.2024, letzter Zugang: 2.3.2025).

Rothbard, Murray (1962/ 2001): Man, Economy and State. Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn, Alabama.

Rothbard, Murray N. (1982/ 2002): The Ethics of Liberty. New York University Press, New York.

Sargent, Thomas / Wallace, Neil (1981): Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 531, 1-17.

Schnabl, Gunther (2023): Seventy-five Years West German Currency Reform: Crisis as Catalyst for the Erosion of the Market Order. Kyklos 77, 1, 77-96.

Schnabl, Gunther / Sonnenberg Nils (2021): Argentina's Creative Approaches to Debt Write Offs. American Institute for Enterprise Research. URL: thedailyeconomy.org/article/argentinas-creative-approaches-to-debt-write-offs(publiziert: 30.5.2021, letzter Zugang: 3.3.2025).

Singer, Hans (1950): The Distribution of Gains Between Investing and Borrowing Countries. American Economic Review, 40, 473-485.

Sturzenegger, Frederico (2019): Yes, Macri Failed on the Economy. But It Wasn’t All for Naught. Americas Quarterly. URL: www.americasquarterly.org/article/yes-macri-failed-on-the-economy-but-it-wasnt-all-for-naught/(publiziert: 31.10.2019, letzter Zugang: 28.2.2025).

Sturzenegger, Frederico (2025): Chainsaw and Deregulation: The First Year of Javier Milei’s Presidency. Bing-Video. URL: www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo (publiziert 23.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 28.1.2025).

The Economist (2024): An interview with Javier Milei, Argentina’s President. URL: https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2024/11/28/an-interview-with-javier-milei-argentinas-president (publiziert 28.11.2024, letzter Zugang: 28.1.2025).

TAZ (2025): Ökonom über Mileis Wirtschaftspolitik: ”Das industrielle Argentinien wird verschwinden“ Interview mit Hernán Letcher, URL: taz.de/Oekonom-ueber-Mileis-Wirtschaftspolitik/!6056578/ (publiziert 1.1.2025, letzter Zugang: 21.2.2025).

Vasquez, Carlos (2024): Aerolíneas Argentinas podría dejar de operar por falta de gerente de operaciones. Radioinforme 3. URL: https://www.cadena3.com/noticia/radioinforme-3/aerolineas-argentinas-podria-dejar-de-operar-por-falta-de-gerente-de-operaciones_397040 (publiziert 19.9.2024, letzter Zugang: 4.3.2025).

Weltwirtschaftsforum (2024): Davos 2024: Special Address by Javier Milei, President of Argentina, URL: www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/special-address-by-javier-milei-president-of-argentina/ (publiziert: 18.1.2024, letzter Zugang: 7.5.2024).

Williamson, John (2000): "What Should the World Bank Think About the Washington Consensus?" World Bank Research Observer. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 15, 2, 251-264.

World Bank Group (2024): Poverty Traps in Argentina. World Bank Group, Washington, D.C.

_______________________________________________________

1 We would like to thank Tom Bugdalle for his outstanding research assistance and Thomas Mayer for his excellent comments.

2 The complete liberalisation of international capital movements is a prerequisite for free trade.

3 UFor example, companies are only allowed to acquire foreign currency for operational purposes and must continue to exchange export earnings into pesos.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.