Chinese exports are putting the German automotive industry under enormous pressure. Brands such as BYD, Geely and Xpeng are entering the German market and offering electric cars at prices that seem almost unattainable for German manufacturers. German customers are still reluctant to buy Chinese cars, but the threat to domestic manufacturers is becoming increasingly real.

The alarm bells are already ringing in company management. VW brand boss Thomas Schäfer has stated that VW is no longer competitive.1 Politicians have also positioned themselves. EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is rumoured to be considering punitive tariffs on Chinese cars in order to protect European industry from unfair competition.2

Should politicians intervene to protect domestic companies, sales markets and local jobs from Chinese competition?

To get a better picture of the answer to this fundamental question, we take a look at the 1970s and 1980s in our second article in our series on the automotive industry.

At that time, the Japanese automotive industry experienced an unprecedented rise and celebrated export successes on the American and European sales markets. At the time, Japan was regarded as a prime example of long-term, strategically motivated industrial policy and therefore structurally superior to the West. Local manufacturers feared that the "Japanese threat" would lead to their downfall.

Japanese politics, in particular the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), had a decisive influence on the development of the Japanese automotive industry. However, the decisive reasons for international competitiveness developed against the ideas of Japanese politics. Although the state provided start-up aid, it could not foresee the path the industry would have to take in the long term in order to become an international leader.

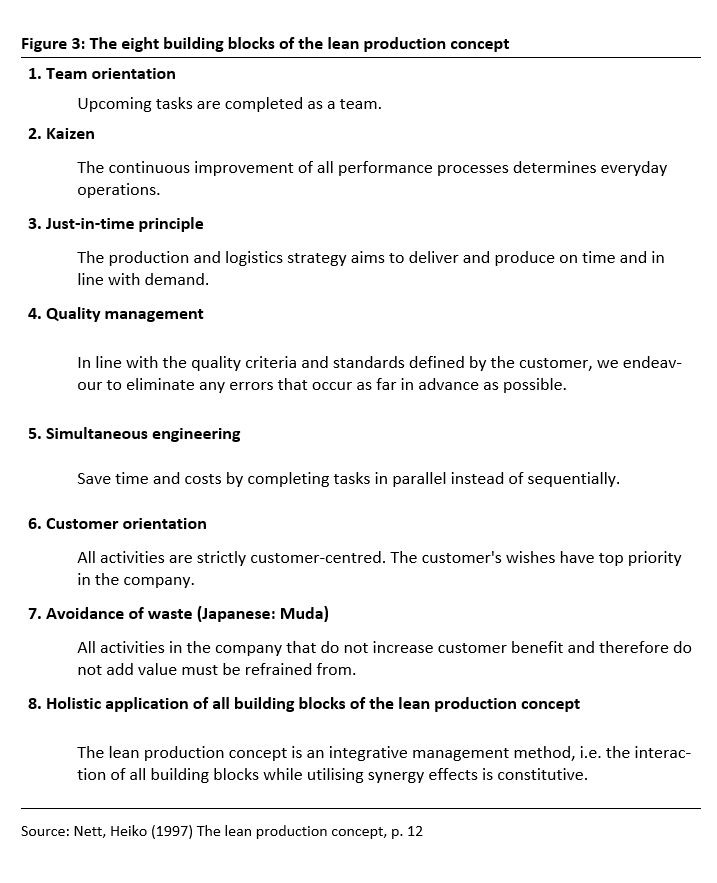

The actual cause of the Japanese competitive advantage was the Toyota Production System (TPS), also known in the West as lean production since 1988. The core elements of the innovative production process are continuous improvement (Kaizen), just-in-time delivery and production, and the avoidance of waste (Muda). The TPS was much better suited to satisfying the dynamic customer demand of the international sales markets than the mass production method of Taylorism that still prevailed. The TPS and later the western adaptation of lean production represented a fundamental innovation not only in terms of production processes, but also in terms of the entire management and organisation of industrial companies.

In the 1970s, the USA and Europe initially failed to recognise the true reasons for their own inferiority and blamed the export success of Japanese manufacturers on "unfair competition" in the form of state control. The reaction in the USA and parts of Europe consisted of a protectionist trade policy, which was intended to protect domestic manufacturers against Japanese competition and secure jobs and sales markets.

As a result of government intervention, the necessary adjustments to the corporate structures and production processes of American and European manufacturers were neglected. Protectionism reduced the pressure to innovate and weakened the market position of European and American manufacturers.

Even if there are differences between the Japanese threat at the time and the Chinese threat today, the mistakes of the past should not be repeated.

1. The rise of the Japanese automotive industry between 1945 and 1980

After losing the Second World War, Japan was faced with the fundamental political decision of what importance should be attached to the development of a national car industry. While MITI wanted to develop car manufacturing into a strategic national sector, there was opposition from other political players. The Japanese parliament declared: "As far as the manufacture of motor vehicles is concerned, it is better to concentrate on the production of lorries and buses and dispense with passenger cars. Steel is produced cheaply from iron from Lake Michigan in the USA. From this point of view, it is economically advisable to forego the production of cars."3 The Governor of the Bank of Japan explained: "Attempts to set up automobile production in Japan are pointless. This is a period of international specialisation. America can produce cheap, high-quality automobiles."4 Initially, MITI's view did not prevail.

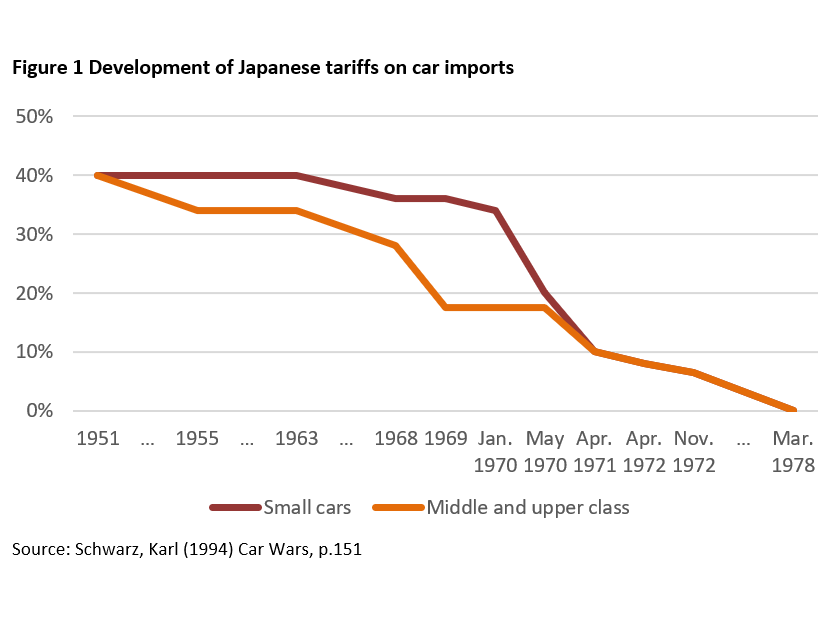

The turning point in this issue came with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, when the American government ordered 12,000 military vehicles from Japan. This order was an initial spark for the Japanese post-war economy. The Prime Minister at the time was enthusiastic: "The war is a gift from the gods"5 In the years that followed, Japan developed its domestic automotive sector with the help of a consistent industrial policy. While the government enforced strategic technology import subsidies, direct investment by foreign manufacturers was largely prohibited. In addition, strict import restrictions were established in the form of foreign exchange restrictions, high customs duties and taxes.

The Japanese government modelled itself on the German concept of the "educational tariff" according to Friedrich List, which the German Reich had also introduced in response to the American threat posed by Ford imports to Germany in the mid-1920s.6 The measures had a clear effect in Japan. In 1954, imports accounted for 90% of the Japanese automotive market, but by 1971 this figure had fallen to just 0.5%. 7

On the other hand, imports of vendor parts and production machinery remained duty-free. On the financing side, there were generous depreciation options, favourable loans from the Japan Development Bank and direct subsidies. The Bank of Japan allocated funds to commercial banks to be channelled to the automotive industry.8

In 1956, MITI founded the "Auto Parts Committee". In three 5-year plans, the supplier industry was to be reduced to a few high-performance suppliers. In the first 5-year plan, the strongest companies were selected and given special access to the Japan Development Bank. This measure also had a signalling effect for the financing of private commercial banks. After consolidation, the second step was to reduce costs by 25 % in the early 1960s. This was also extremely successful. A close network of efficient suppliers was created. These became so strong that MITI was no longer able to push through its desire for a third 5-year plan in 1966.9

An important factor in the development of the Japanese automotive industry is the organisational form of the "Keiretsu". These company mergers had largely emerged from the large company conglomerates of the pre-war period, which the Americans had broken up. Although there was no holding structure, synergy effects were utilised, which were seen as a great advantage both in Japan and in the West. The image of "Japan Incorporated" emerged under the strict leadership of MITI, which seemed superior to Western corporate structures. In the late 1980s, an influential American study came to the conclusion that Western investors were often too impatient and ill-informed. In contrast, the Japanese corporate system is long-term orientated, well informed and quick to act when action is needed.10

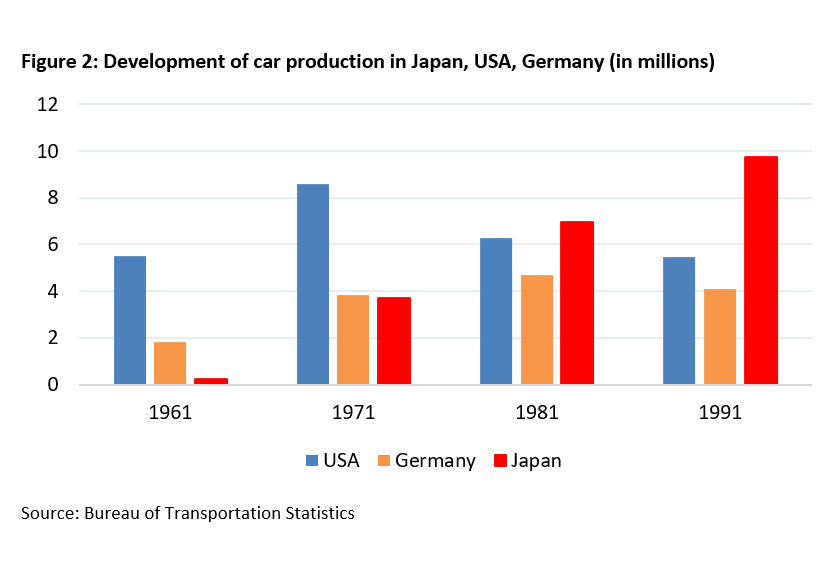

The success of the Japanese automotive industry can be illustrated by the production figures. In 1981, Japan produced the most cars in the world. Whereas in 1961 almost half of all cars worldwide were produced in the USA, in 1991 the figure was only around 15 per cent.

The direct and indirect influence of politics on the beginnings of the development of the Japanese automotive industry is undeniable. However, the decisive course for the international success of Japanese companies was set against the wishes of MITI. At the end of the 1960s, MITI wanted to enforce the American production system of mass production by maximising economies of scale with a relatively narrow product range. To this end, the fragmented industry in Japan was to be reduced to a small number of companies, similar to the "Big Three"11 in the USA. The aim was to create a national champion without foreign shareholders.12

The smaller companies defended their independence against this plan. Mitsubishi reacted by bringing in Chrysler as a foreign shareholder. MITI was only informed of this after the transaction had been completed. Ford acquired a stake in Toyo Kogyo (Mazda). General Motors acquired Isuzu. In this way, the smaller companies defended themselves against capture by the Japanese market leaders Toyota and Nissan. The Japanese government responded with a law that limited the share of foreign investors in Japanese companies to 50 per cent. The plan for a national champion without foreign shareholders was thwarted.13

Even more decisive than the defeat on the issue of market structure was the defeat of MITI when it came to specifying production processes based on the American model. The companies, above all Toyota, recognised from the outset that the concept of mass production was neither suitable for the Japanese sales market nor for the Japanese labour market.14

On the one hand, the Japanese market was relatively small and heterogeneous compared to the USA. Secondly, there was a shortage of production factors in Japan after the Second World War. Larger material stocks were neither possible nor did they fulfil the Japanese desire for efficiency. The most important factor was the organisation of the workforce. The American occupying power after the Second World War enforced the trade union system in Japan by decree against Japanese resistance. These trade unions became politically radicalised in the course of the emerging East-West conflict and became a disruptive factor for both the Japanese and the Americans due to their communist aspirations. As an evasive reaction to this development, Japanese companies founded their own company trade unions. In contrast to the industry unions in the USA and Europe, the Japanese company unions orientated their loyalty towards the success of their own company.

As a result, a culture of cooperation between management and labour prevailed in Japan. The worker was assigned a more responsible position, which stood in contrast to the standardised, repetitive tasks in mass production. The engineer Taiichi Ohno perfected the new form of organisation into the Toyota Production System15 , which later became known in the West as lean production and became established worldwide as an alternative to the Taylorist concept of mass production. This concept relied on workers who were involved in the production process, who were able to think for themselves and who had to constantly identify and communicate opportunities for improvement or bottlenecks.16

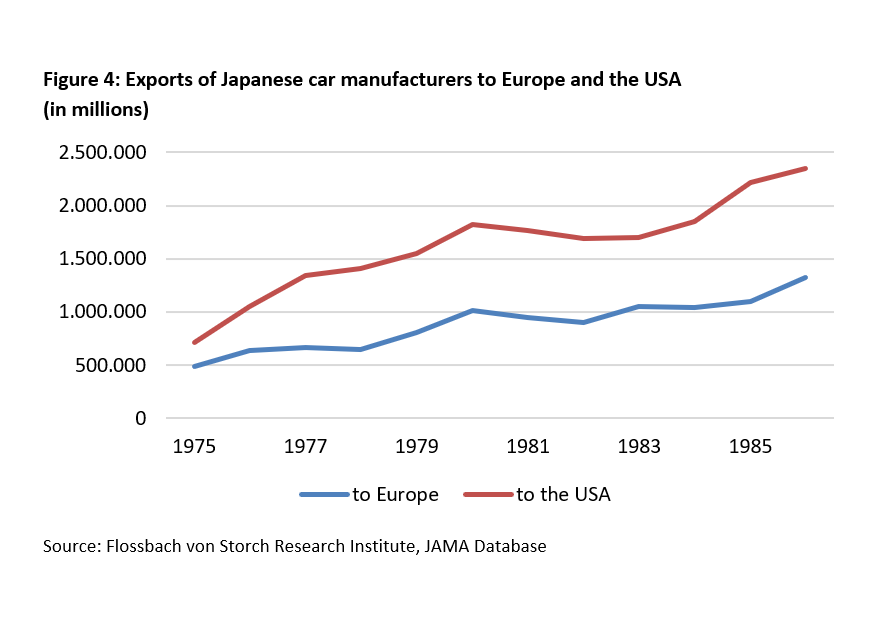

The export figures of Japanese car manufacturers to the sales markets in Europe and the USA are proof of their success. The slight declines between 1980 and 1982 can be explained by voluntary self-restriction agreements that were negotiated with Japan in the USA and individual European countries in order to protect the domestic markets.

2. The rise and fall of the US automotive industry between 1945 and 1985

The general conditions for the development of the US automotive industry were favourable until the early 1970s. Rising mass prosperity created a middle class with purchasing power, which meant that there was no saturated market for a very long time. The car had been deeply embedded in American culture since the 1950s at the latest and became an important social symbol of prosperity and freedom. Although politicians did not pursue an explicit industrial policy to expand the automotive industry, they prioritised the expansion of the road network over the railways, thus creating an important framework. Thanks to Texas' oil reserves, petrol was relatively cheap in the USA from the outset. Finally, in the 1950s and 1960s, foreign producers had difficulty meeting the tastes of American customers for large-engined cars, while the "gas guzzlers" set the standard for American consumers.17 In the 1960s, an oligopoly solidified on the American market, which the three major car manufacturers were able to live with very well. The "Big Three" meant that General Motors, as the industry leader, had a market share of around 50%, Ford around 25% and Chrysler around 15%. 18

With the success of manufacturers in the domestic market, bureaucratisation and complacency set in. Trade unions had linked the acceptance of mass production to high wages. Within management, the finance departments became more important than the engineers. The "car guys" lost importance in favour of the "Wall Street guys". The fixation on short-term balance sheet success led to savings in research and development and in some cases to production on stockpiles. 19

In the early 1980s, Japanese and US researchers jointly investigated the decline of the American automotive industry20 and realised that the oligopoly had damaged competition and the ability to innovate. Products and production processes were standardised, wages were equalised and the focus of competition was on the marketing departments. The biggest risk for companies was a prolonged strike at a plant or brand, which is why generous wage agreements could be enforced. Bureaucracy and costs spiralled out of control. "Few saw the problem until the market shifted dramatically towards smaller cars and the Japanese demonstrated how to produce higher quality cars at lower cost."21

At the beginning of the 1970s, the US market suffered a severe external shock as a result of the first oil crisis. In the second half of the year, the price of crude oil rose by 180 per cent within six months, making the "gas guzzlers" too expensive for many households to maintain. The models were not designed to meet the new customer requirements for smaller petrol-saving models. The success of the past few years increased self-assurance and made it difficult to reorganise quickly. Companies failed to recognise the shift in demand, even though it had already begun before the oil crisis. Rising prosperity and increasing female employment increased the demand for smaller second cars.22

In the 1970s, the relationship between manufacturers and politicians also deteriorated. The government increasingly interfered in production, both through safety regulation and increasingly through environmental legislation.

"By the mid-1970s the relations between Washington and Detroit were increasingly testy. Federal officials regarded the automakers as untrustworthy obstructionists, and auto company managers viewed the government as intrusive and ignorant of engineering realities."23

Nevertheless, the US government protected American car manufacturers in order to preserve domestic jobs. In 1971, Nixon not only announced the end of the dollar's gold peg, but also imposed a ten per cent import tariff on Japanese cars. This measure led to a short-term jump of 10 to 15 per cent in the share prices of US car manufacturers on the New York Stock Exchange. Nevertheless, Chrysler required a government rescue programme in 1979, which enabled the company to be successfully restructured.

In 1980, the US and Japanese governments agreed on a "voluntary self-restraint agreement", in which a maximum limit of 1.8 million imported cars per year was agreed. With this measure, US President Jimmy Carter attempted to give in to the political pressure caused by the recession and job concerns in the 1980 election year. The newly elected Reagan administration continued the protectionist policy in order to pre-empt further protectionist demands from the US Congress. The self-restriction agreement primarily had negative consequences for American consumers, as fewer cars could be sold at a higher price. Indirectly, they also posed a problem for American manufacturers. As Japanese manufacturers used the import restrictions to upgrade their limited edition cars, they were able to realise a higher profit margin on the US market. As a result, competition between the models of Japanese manufacturers and the models of the "Big Three" became even more intense. When the USA lifted the import restrictions in 1985, they had paid off for the Japanese companies to such an extent that they were unilaterally extended by the Japanese government. Neither the tariffs nor the self-restriction agreement were part of a strategic industrial policy on the US side.

The US automotive industry missed out on the shift in domestic demand towards smaller cars. Thanks to the concept of lean production, Japanese competitors were able to respond better to this demand and take market share away from American car manufacturers. Politicians initially responded with tariffs and later with a voluntary self-restraint agreement. This policy was particularly detrimental to the American consumer, who either had to pay more or could not buy the car because there was a quantity restriction. Japanese manufacturers were able to benefit in the long term as they were able to attack American manufacturers in the higher-priced segment.

3. The European automotive industry's response to the Japanese threat

Trade relations between Japan and Europe were largely conflict-free until 1975, as Japanese export activities were focussed on South East Asia and the USA. The market share of Japanese cars in Europe at this time was around 0.6 per cent.24 The "Nixon shock" for the Japanese car industry turned into a "Japan shock" for the European car industry, as Japanese export efforts were now increasingly focussed on Europe. In addition, the Japanese domestic market showed signs of saturation, which is likely to have further motivated export efforts. The second oil crisis hit the Europeans harder. Although European manufacturers did not have the same problems with their unsuitable models as the Americans, the Japanese were able to gain market share with a good price-performance ratio, particularly in non-protected markets. This was partly due to high European wage levels combined with dissatisfaction with the production conditions of mass production, which led to falling labour hours. In the mid-1970s, the respective national manufacturers dominated the European submarkets.

The Japanese offensive in Europe exposed the systematic inconsistencies in the European integration process. The European Community was fundamentally committed to the principle of free trade out of the conviction that it leads to economic growth, jobs and personal freedom. This conviction led to the extensive liberalisation of the internal market being enshrined in the Treaties of Rome in 1957. The international agreement GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) of 1947 also pursued the goal of liberalising world trade and thereby promoting general prosperity.

Although the institutions of the post-war order were fundamentally geared towards free trade, the rules allowed for exceptions. As a result, there was a big difference between the fundamental intentions expressed in the rules and the immediate interests in the political debate in which the rules had to be interpreted and applied. The typical arguments used in Europe to justify the restriction of free trade were unfair trade practices, anti-price dumping measures and excessive social costs.25

In the words of economist and globalisation advocate Jagdish Bhagwati: "Fair trade is a handy concept, which allows intransparent and highly protectionist non-tariff barriers and which, at the same time, appeals to the public sense of what is 'right' and to what some economists claim are new justifications for protection."26

The legal scope for this was provided both in the GATT agreement and in the Rome Treaties, both at national and European level.27 Voluntary export restraints, which were not prohibited by either the GATT or the Rome Treaties, were a popular instrument. These were bilaterally negotiated agreements intended to protect domestic markets against excessive competition.

Italy was the most strictly sealed-off country. In 1970, an upper limit of 1,000 imported Japanese cars was imposed. In 1978, this limit was raised to 2,200 cars.28 In France, the market share of Japanese manufacturers rose rapidly from a low level. In 1970, Japanese cars had a market share of 0.8 per cent, by 1974 it was already 2.7 per cent. Manufacturers and politicians threatened the Japanese with "unilateral retaliation" if the market share rose above 3 per cent. In the UK, the British motor industry association SMMT agreed an upper limit for Japanese cars of 11 per cent market share with the Japanese JAMA.29

Germany had no quotas. As a result, the market share of Japanese cars rose from 6.6 per cent to 10.4 per cent in Germany, Europe's largest sub-market. This led to conflicts within the EC. While European manufacturers such as Renault and Fiat in particular suffered from Japanese competition on the open German market, German manufacturers benefited from the protectionist environment in other European sales markets. Germany came under pressure within Europe, particularly from France. However, rumours that Germany had unofficially negotiated an import restriction with Japan were denied. 30

These fundamental European structural problems were masked at the beginning of the 1980s by a sustained upturn in the entire automotive industry, which also ensured that the pressure to adapt was weakened. Nevertheless, there were intensive structural debates at the political level. The key question remained how to deal with the Japanese competition at European level. The automotive industry felt it was facing unfair competition and warned against opening up the European single market too quickly. The opposite position was taken by the European Commission, in particular the then Trade Commissioner Martin Bangemann. He was in favour of eliminating national quotas and at the same time rejected EC-wide import quotas in principle. Instead, he strove for complete harmonisation of technical regulations and approval provisions with the aim of a uniform EC operating licence. He also advocated that there should be no restrictions on direct investment from outside the EC.31 He received support from Germany from Federal Economics Minister Helmut Haussmann: "Only constant competitive pressure maintains and strengthens the international competitiveness of the industry. The sooner automotive companies prepare for open markets, the better." 32

Both European car manufacturers and national governments were very sceptical about the Commission's liberalisation efforts. Although they fundamentally recognised the need for competition, they were concerned about the dynamics. Moreover, they saw the deficits not in the companies themselves, but primarily in society in general.

Richard Lutz, head of Ford Germany, put it as follows in a discussion about the competitive situation in front of industry representatives in 1981: "It is not the European automotive industry that is not working efficiently, but it is our entire, well-intentioned socio-political system orientated towards leisure and quality of life, which I personally love very much."33

And further:

"All Western governments are currently endeavouring to make our system more efficient again. And that's a good thing. Because we in the West have all become far too fat and comfortable in recent years. The whole Japan wave that is rolling over us is good. (...) The problem is: we have to make sure that it makes us stronger without killing us. Because if we are dead, we can no longer become more efficient. And that's my big worry."34

The car manufacturers also criticised an excessive focus on the theory of free trade, which they shared in theory but felt was not practical. They argued that Europe was damaging itself by focussing too strongly on the principles of free trade policy. The head of the PSA, Jaques Calvert, made this clear. He made an appeal at the IAA 1989:

"Do we want to run the risk of further increasing unemployment in Europe and lowering living standards for the sake of a few abstract theories, only to ultimately create jobs in Japan and condemn Europe to become the employees of Japan Incorporated? Social Europe or open Europe - we have to decide. If there are no more jobs in Europe, there will be no more consumers."35

The then VW CEO Carl Hahn supported his argument: "The Japanese opened their markets when they had consolidated their position. Europe should therefore also base the timing of the opening of its market on its own criteria and not on nice-sounding generalising theories."36

In their study, Womack et al. state that the European car market in the 1980s was so protected by a large number of trade restrictions and national "gentlemen's agreements" that there was little reason to adapt and introduce the lean production concept. The first step towards adaptation was finally taken by Ford. They tried out what they had learnt in Japan.37

The actual paradigm shift that took place in the automotive industry in the middle of the 20th century was the transition from mass production to lean production. In Japan, this production method became established as the Toyota Production System against the will of the regulatory authorities. In the USA, Europe and Germany, protectionist measures delayed adaptation.

Automotive companies learnt their lesson in the early 1990s and largely introduced the lean production concept. In Germany, Opel built a new plant in Eisenach, which set new standards in efficiency throughout the Group. Mercedes adopted the lean production concept in a new plant in Rastatt. At Volkswagen, the Spanish manager Ignacio Lopez took over responsibility for the production processes. He correctly recognised in 1993: "In the past, costs drove car prices up; in the future, car prices will drive costs down." Together with Ferdinand Piech, he endeavoured to modernise the Group. Ultimately, competition through globalisation led to a new increase in competitiveness for the German automotive industry. The adoption of the lean production concept became a prerequisite for surviving globalisation.38

Lean production enabled manufacturers to respond to the changing demand for a wide range of variants while at the same time producing at low cost. The adaptation of the lean production concept was also suitable for German manufacturers because key elements of the concept were not so foreign to the German work culture.

The team orientation in Germany, for example, was based on experience with group work. The position of the worker was more comparable to the ideas of lean production than mass production. Greater scope for decision-making and less monotony were associated with greater self-confidence and job satisfaction.

The principle of Kaizen is understood as a continuous incremental improvement process. Here, too, there is an equivalent in the form of the company suggestion scheme, which the German manufacturers were able to use as a starting point. The major difference was the actual anchoring in the corporate culture. While 61.6 suggestions per employee were submitted per year in Japan in 1989, the figure for European car manufacturers was 0.4.39

The just-in-time principle corresponded to the desire for economy and customer-orientation. The main risk was production downtime due to supply chain problems or strikes. Both risks appeared to be manageable in Germany from the 1980s onwards.

The understanding of quality on which the lean production concept is based found its counterpart in the traditional understanding of quality that has developed since the 1950s under the term "Made in Germany".

Conclusion

With regard to the new challenge from China, two key lessons can be learnt. Firstly, in Japan, the automotive industry was able to assert itself against the government's ideas and thus expand its international competitiveness. A similar form of innovative implementation of corporate strategy against the interests of the government seems much less likely today. Even if Chinese companies have produced many innovations in the past decade, there is a structural risk that they will not be able to assert themselves against the government in key areas in the future.

Secondly, Europe runs the risk of not having internalised the most important lesson from the time of the "Japanese threat". Competition is ultimately decided by the consumer. The history of the automotive industry shows that if competition is hindered too much, innovation processes are blocked and the costs are first borne by the customers and, in the medium term, by the apparently protected companies and employees. The future success of the German automotive industry is closely linked to the intensity of competition.

______________________________________________________

1 See Handelsblatt on 30 November 2023

2 See Handelsblatt on 15/09/2023

3 Hanaeda, Mieko (1982) Der Handelskonflikt zwischen Japan und den EG-Staaten, Munich: Weltforum-Verlag, p.77.

4 Ibid.

5 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 144.

6 List, Friedrich (1842/ 2008) Das nationale System der politischen Ökonomie, Tübingen: Nomos Verlag, see also Immenkötter and Kleinheyer (2023).

7 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 151.

8 Ibid, p. 147.

9 Dyer, Davis; Salter, Malcom; Webber, Alan (1987) Changing Alliances, Boston: Harvard Business School Press, p. 120.

10 Womack, James; Jones, Daniel; Roos, Daniel (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Rawson, p.203.

11 The "Big Three" in the USA are General Motors, Ford and Chrysler.

12 Womack, James; Jones, Daniel; Roos, Daniel (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Rawson, p. 48.

13 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 155.

14 Ibid. 158.

15 Ohno, Taiichi (1988) Toyota Production System, Productivity Press, Cambridge Massachusetts. The book was published in Japan in 1978 and translated into English in 1988.

16 Womack, James; Jones, Daniel; Roos, Daniel (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Rawson, first uncovered this development at the end of the 1980s and coined the term "lean production".

17 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 113.

18 Rae, John (1984) The American Automobile Industry, Boston: G.K.Hall, p. 107.

19 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 172.

20 Cole, Robert and Yakushiji, Taizo (1984) The American and Japanese Auto Industries in Transition: Report for the Joint US-Japan Automotive Study. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

21 Ibid, p. 89.

22 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p.74.

23 Dyer, Davis; Salter, Malcom; Webber, Alan (1987) Changing Alliances, Boston: Harvard Business School Press, p. 54.

24 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 196.

25 Schuknecht, Ludger (1992) Trade Protection in the European Community, London: Routledge, p. 2.

26 Bhagwati, Jagdish (1991) The World Trading System at Risk. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, p. 14.

27 Schuknecht, Ludger (1992) Trade Protection in the European Community, Routledge

28 Schwarz, Karl (1994) Car Wars, Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, p. 199.

29 Ibid. S. 200.

30 Ibid. S. 204.

31 Ibid. S.222.

32 Ibid. S. 227.

33 In: Röper, Burkhardt (1985) Strukturpolitische Probleme der Automobilindustrie unter dem Aspekt des Wettbewerbs, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 40.

34 In: Röper, Burkhardt (1985) Strukturpolitische Probleme der Automobilindustrie unter dem Aspekt des Wettbewerbs, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 42.

35 In the FAZ of 20 September 1989.

36 In the Süddeutsche Zeitung on 20 November 1989.

37 Womack, James; Jones, Daniel; Roos, Daniel (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Rawson, p. 239.

38 Nett, Heiko (1997) Das Lean-Konzept, Norderstedt: Diplomica Verlag, p.17.

39 Womack, James; Jones, Daniel; Roos, Daniel (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, New York: Rawson, p. 97.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.