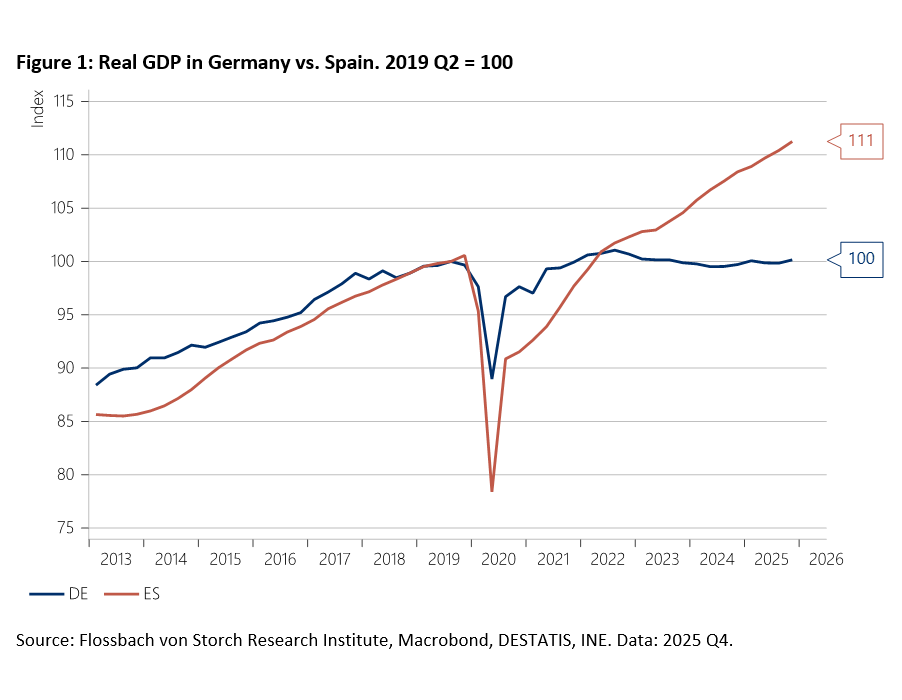

While the Spanish economy stood out in 2025, Germany continued to disappoint. Spain’s real gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 2.6 percent, whereas Germany managed a meagre 0.4 percent. This divergence has been evident since the pandemic. Although Spain’s GDP contracted far more sharply than Germany’s during the 2020 lockdowns, Spain’s output today stands 11 percent above its 2019 level, while Germany’s remains stuck at roughly the same level (Figure 1).

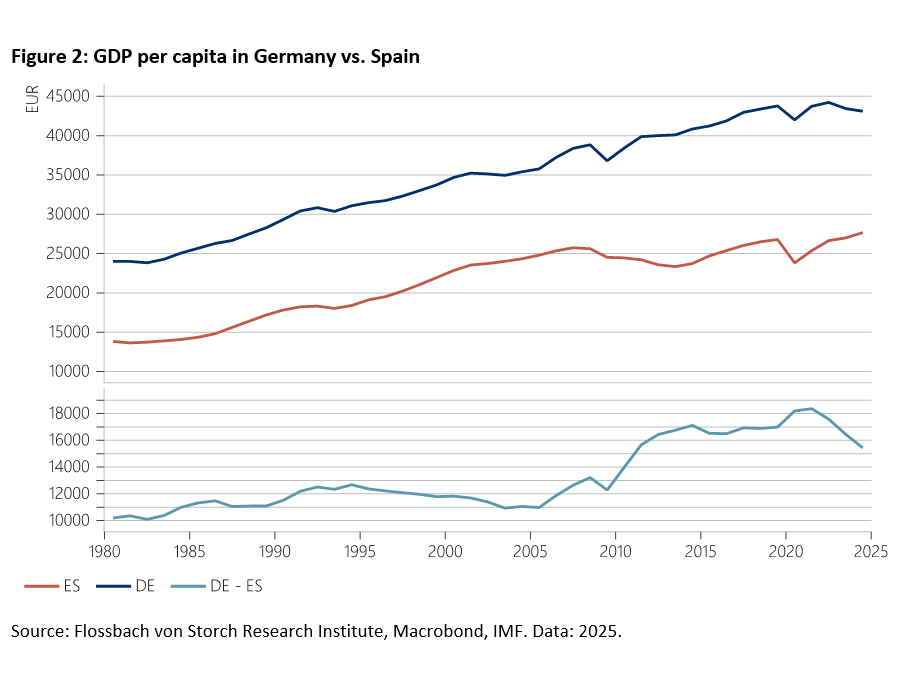

At first glance, this might look like the convergence promised by European monetary union (EMU). Since 2020, living standards in Spain and Germany, measured by GDP per capita, have moved closer together. Yet in absolute terms they remain further apart than before the euro was introduced. Moreover, the narrowing gap does not reflect Spain rapidly catching up. It reflects Germany in trouble: real GDP per capita has been declining since 2022 (Figure 2).

No Spanish productivity miracle

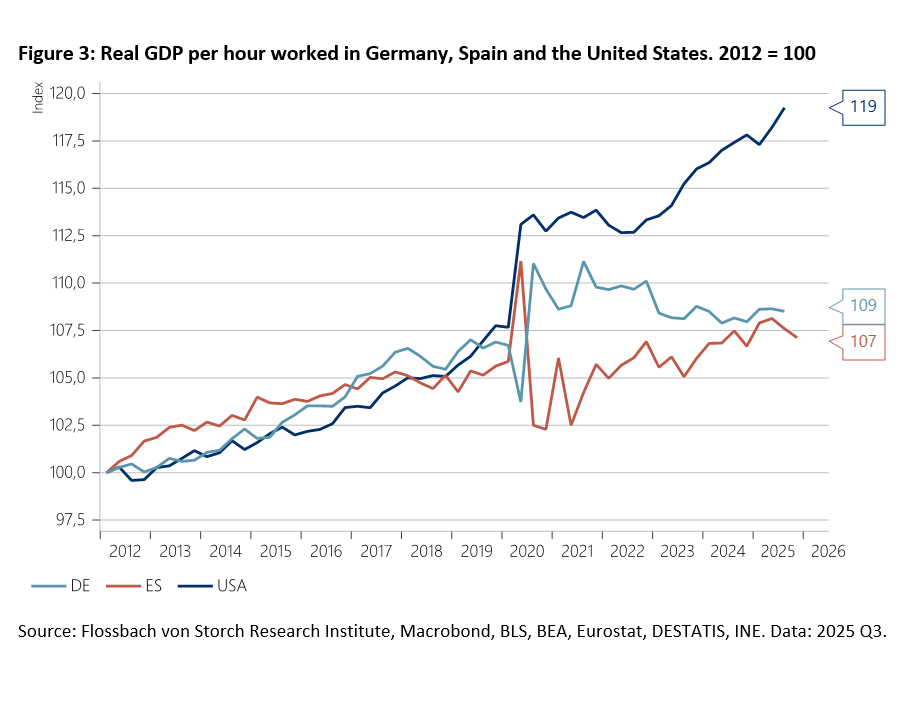

In the long run, economic growth comes from using factors of production more efficiently. The strong performance of the United States in recent years illustrates the point. Since 2012, US labor productivity, measured as real output per hour worked, has increased by 19 percent. In Spain and Germany, it has risen by only 8 percent (Figure 3). Spain’s stronger growth relative to Germany, therefore, cannot be attributed to superior productivity gains.

Demography and Migration

If productivity has not improved more in Spain than in Germany, the growth gap must be explained by the number of workers. Employment has increased by 11 percent in Spain since the end of 2019, compared with just 1 percent in Germany. That translates into 2.3 million additional workers in Spain, versus barely 500,000 in Germany.

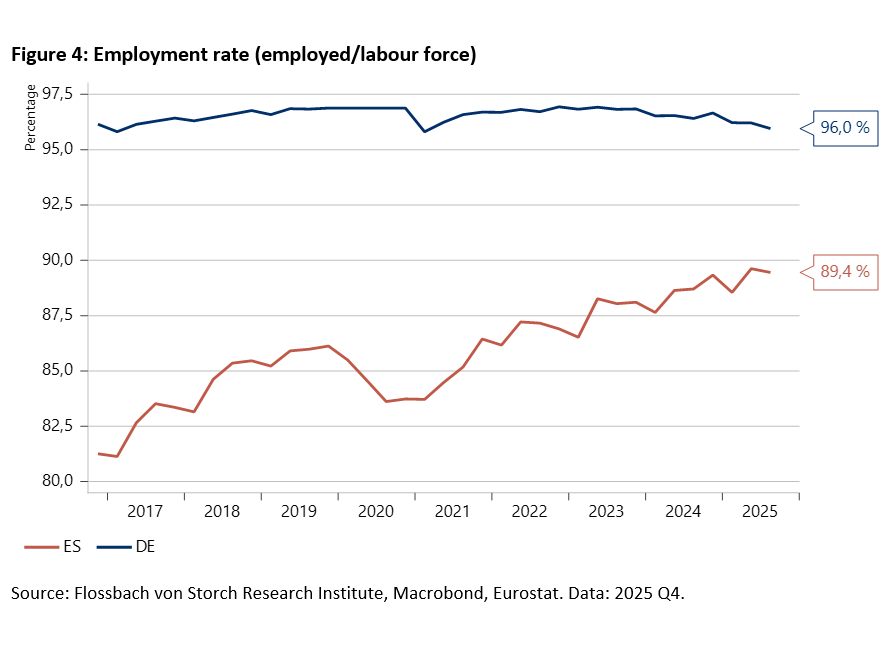

Part of the explanation lies in initial conditions. Spain entered the pandemic with significantly higher unemployment. At the end of 2019, the employment rate, defined as the share of employed in the total labor force, stood at 85 percent in Spain. Germany was close to full employment. When the recovery began, Spain still had a sizeable pool of unemployed workers ready to take up jobs (Figure 4).

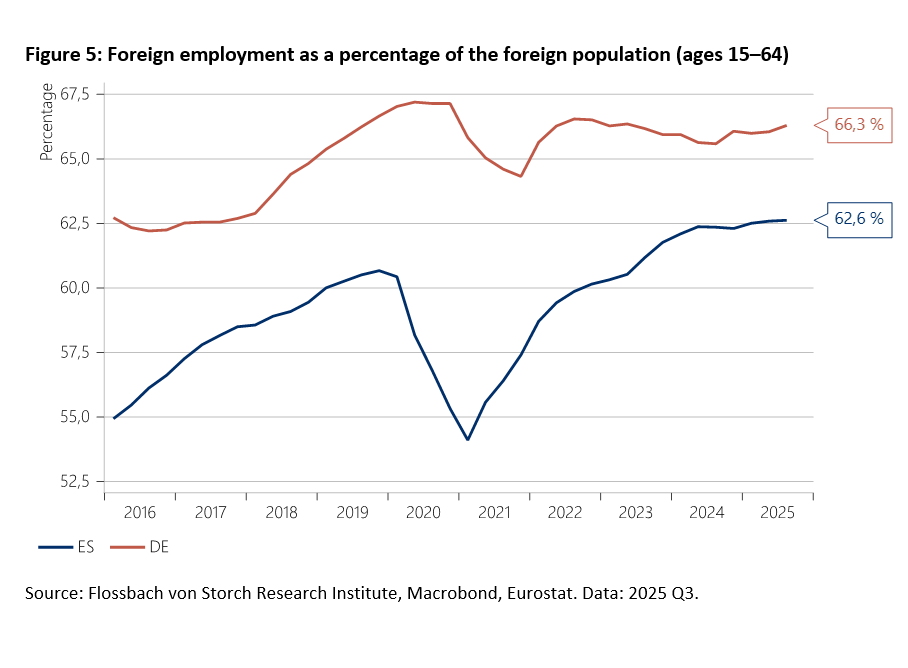

Another factor is migration. Since the end of 2019, both countries have seen a similar inflow of working age migrants aged 15 to 64, 1.54 million in Spain and 1.46 million in Germany. Yet the employment rate among the foreign population has declined slightly in Germany, while it has increased in Spain (Figure 5).

Institutional differences likely explain this divergence. In Germany, migrants typically need both a residence permit and a work permit before they can take up employment. In Spain, informal employment without a permit is more often tolerated. During the months or even years that legal procedures in Germany can take, particularly in asylum cases, the German government provides more generous social benefits. Spain, by contrast, has since 2025 offered the prospect of regularization after two years of residence, provided no asylum claim was filed and no associated benefits were received. The incentive structure is clear. Migrants seeking rapid labor market integration face fewer barriers in Spain than in Germany.

European Union Transfers

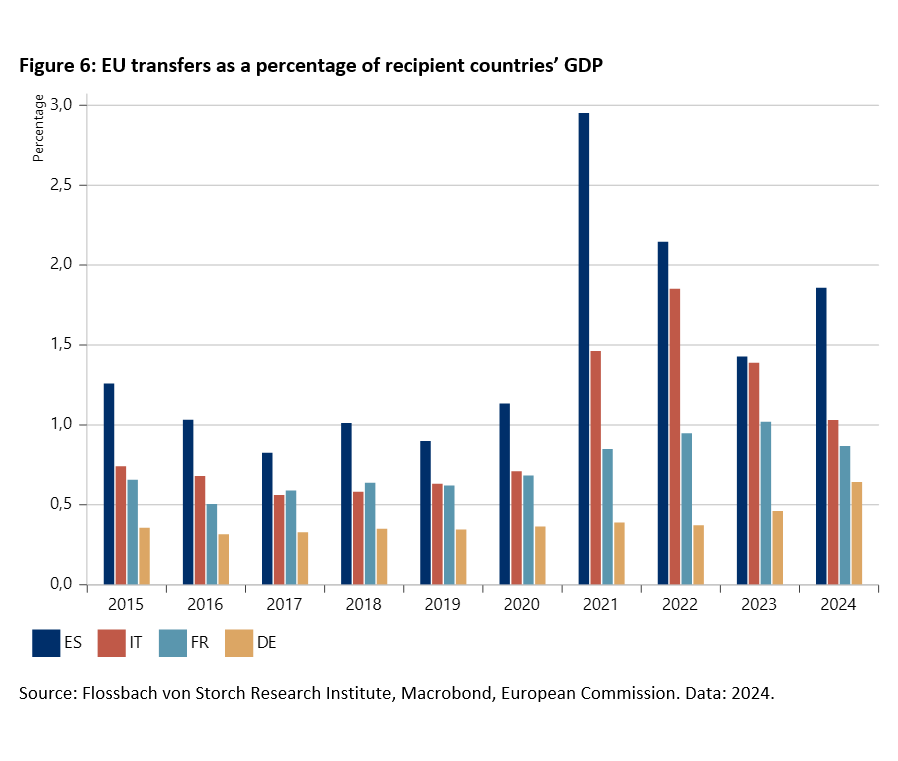

Another factor behind Spain’s stronger performance is fiscal transfers from the European Union. Before the pandemic, transfers to Spain amounted to roughly 1 percent of GDP, compared with between 0.3 and 0.4 percent in Germany (Figure 6).

Following the Covid crisis, transfers to Spain increased substantially under the debt financed programs SURE and NextGenerationEU. By 2024, payments from Brussels reached 2 percent of Spanish GDP, whereas Germany received transfers equivalent to 0.6 percent of its GDP.

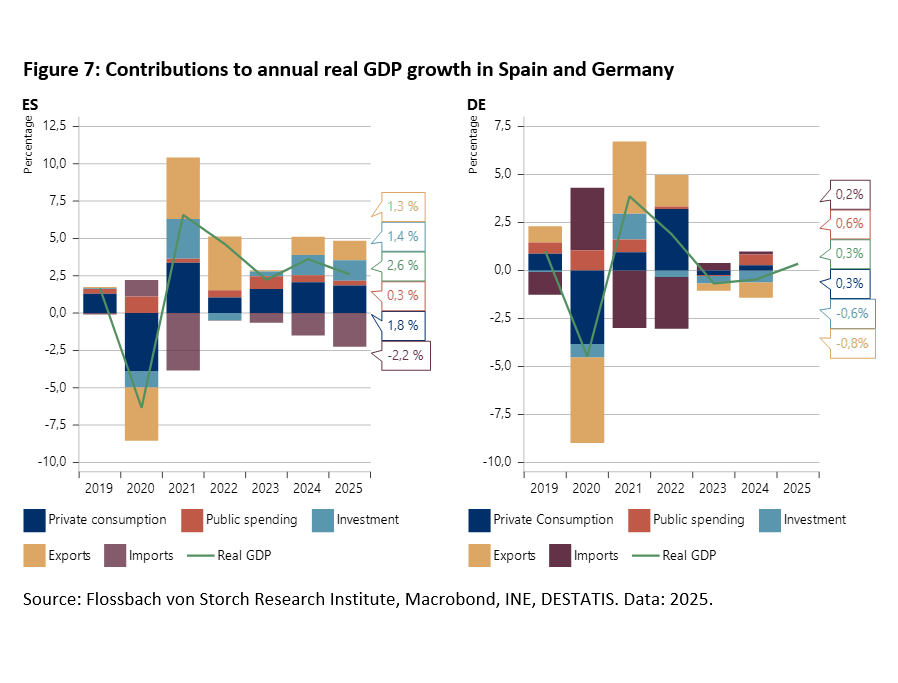

EU programs are primarily designed to finance investment. In 2021, investment contributed decisively to Spain’s GDP recovery (Figure 7). In 2024 and 2025, it was the second most important growth driver after private consumption. We cannot determine precisely how much investment would have taken place without EU transfers. Still, it is reasonable to assume that part of the expansion was made possible by them. In Germany, by contrast, investment made a negative contribution to GDP growth in 2023 and 2024.

Conclusions

Since 2012, labor productivity per worker in both Spain and Germany has increased by only about 3 percent, despite fifteen years of technological progress, including artificial intelligence. Spain’s stronger growth, therefore, rests not on higher efficiency but on a larger workforce. In Germany, employment remains close to pre pandemic levels.

Migration has contributed more to employment growth in Spain than in Germany, largely due to differences in labor market and social policies. Germany typically requires formal legal status, and work permits before employment begins. Spain often tolerates early entry into the informal sector before subsequent regularization. This approach facilitates faster labor market integration.

EU transfers, largely directed toward investment, appear to have supported Spain’s growth and, with it, the integration of migrants into the labor market. They do not alter the underlying diagnosis. Without sustained gains in efficiency and productivity, Spain’s rapid growth will be difficult to maintain. Investors looking for solid long-term growth in Europe will have to continue waiting for structural reforms, in Spain as well as in Germany.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.