COMMENT. The dispute over Greenland has also highlighted the US debt, the financing of which is Washington's Achilles heel.

For 66 years, it quietly searched for investments on the capital market in tranquil Gentofte. Until 20 January 2026, that is, when the pension fund AkademikerPension, founded in 1960, caused a worldwide stir. The Danes announced that they would be selling their portfolio of US government bonds worth 100 million dollars on the market by the end of January.

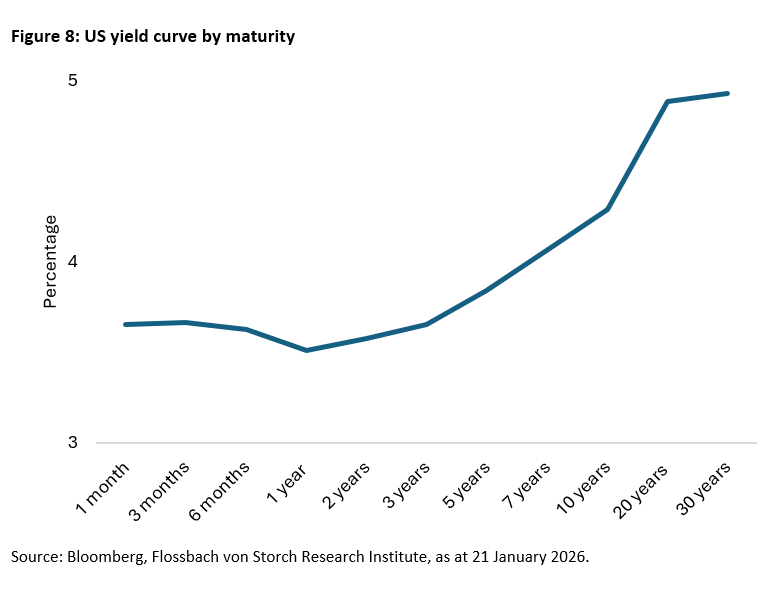

The news would normally have been worth no more than a footnote. But in the context of US ambitions in Greenland, customs threats and possible defensive measures by Europe, AkademikerPension moved the markets. The price of gold jumped to a record high, while US government bonds crumbled in value. The yield on 30-year US government bonds rose by eight basis points (0.08 percentage points) to 4.92 per cent.

The concern: if larger European institutions were to join the Danes, it could cause a shock on the financial markets. In spring 2025, confusing tariff announcements by the US president were enough to trigger a sharp slump in US government bonds. At that time, the yield on 30-year US government bonds rose by almost 0.7 percentage points to 5.09 per cent within seven weeks.

Even though Donald Trump backtracked on his tariff threats on Wednesday evening, given the erratic US policy, the question remains as to what the situation is with US government debt and how great the threat of possible large sell-offs of US government bonds would be.

Achilles heel: US government debt

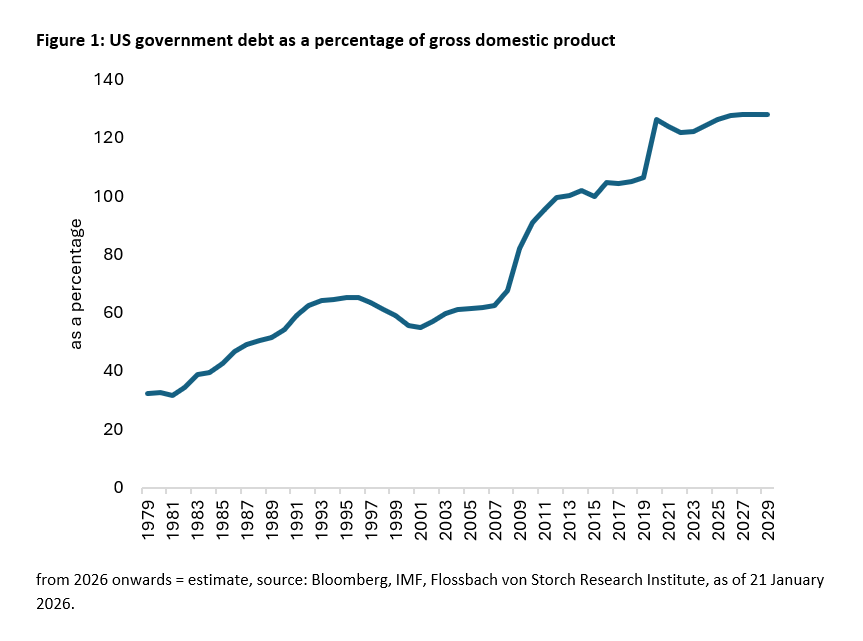

Government debt has become the Achilles heel of the US. Before the financial crisis at the end of 2007, it stood at 62.6 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) and has since doubled (Figure 1).

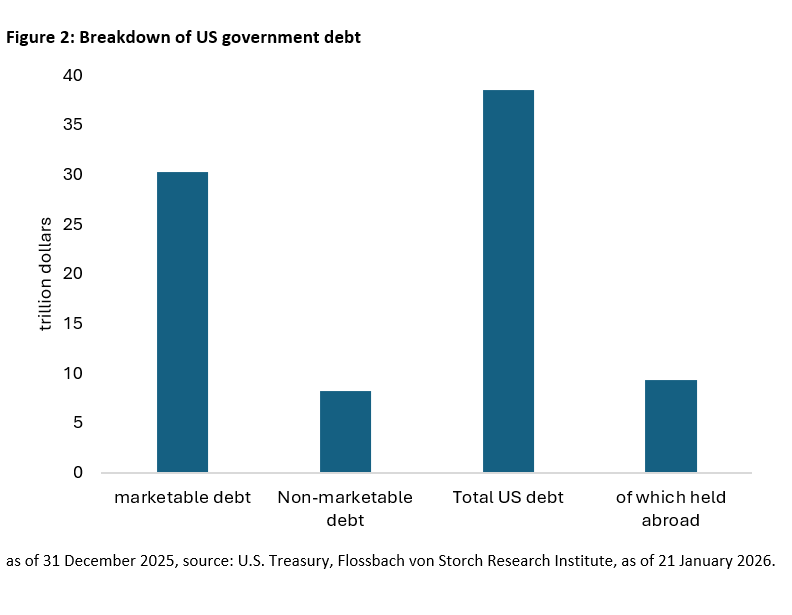

In absolute terms, it amounts to 38.5 trillion dollars, of which just under 30.3 trillion is marketable (usually listed on the stock exchange via bonds). Just under $9.4 trillion of this is held by foreign countries (Figure 2). According to the latest data from the Federal Reserve of St. Louis as of 14 January 2026, the US Federal Reserve held a good $4.24 trillion in US Treasuries.

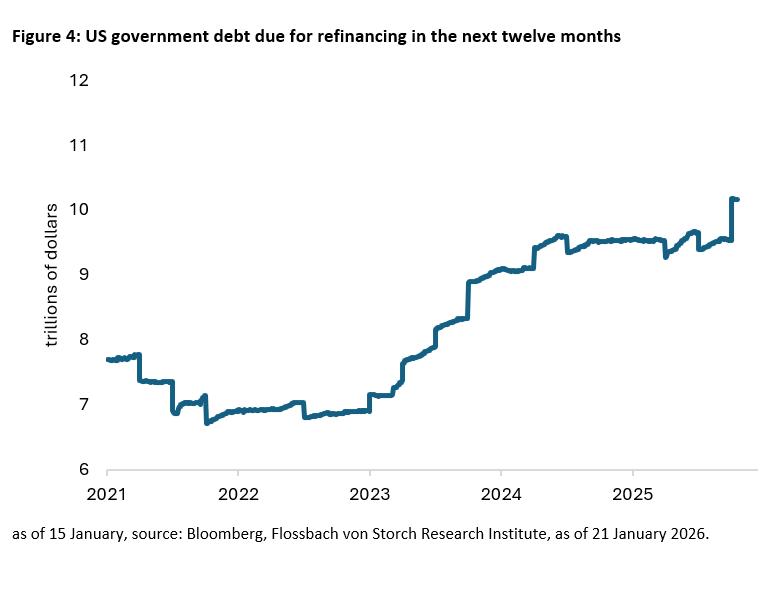

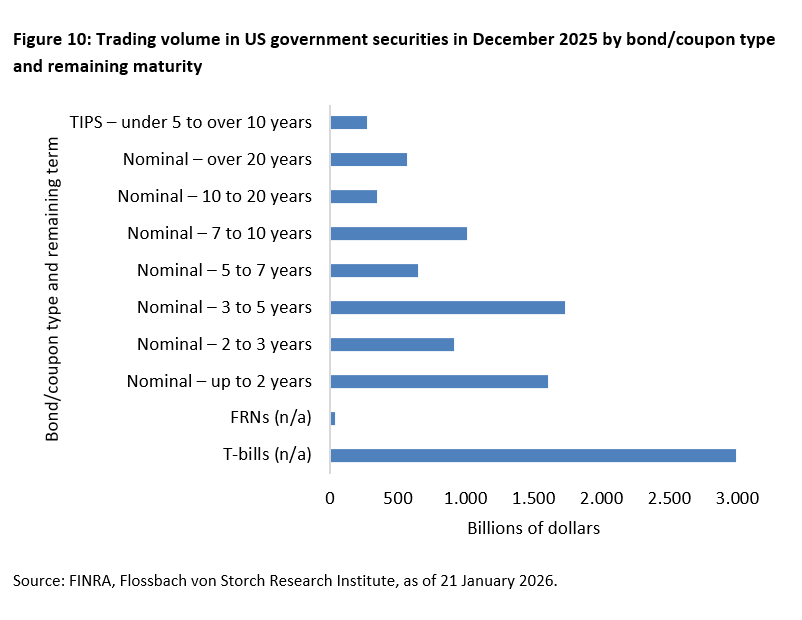

An important role is played by short-term Treasury bills (T-bills), which are issued weekly by the US Treasury with maturities of 4, 8, 13 and 26 weeks, and monthly with a maturity of 52 weeks. The US refinances ("rolls") around one-fifth of its marketable debt in this way. Last year, the monthly volume of new T-bills ranged between around 1.8 and 2.5 trillion dollars. All issues, including longer-term securities, amounted to a volume of 2.1 to 2.9 trillion dollars per month in 2025. In addition to T-bills, these include Treasury notes (T-notes) and Treasury bonds (T-bonds) with fixed coupons, floating rate notes (FRNs) with variable interest rates, and Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) linked to consumer prices.1

High refinancing requirements in 2026

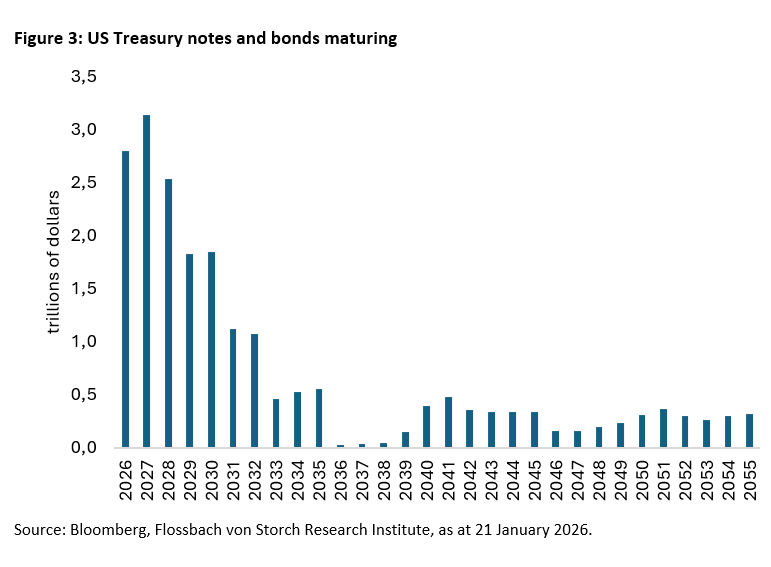

Excluding T-bills, $2.8 trillion in longer-term bonds are due for refinancing this year, followed by $3.1 trillion and $2.5 trillion in the next two years (Figure 3).

Added to this are the US budget deficits, which also need to be financed. For the 2026 fiscal year (1 October 2025 to 30 September 2026), 1.7 trillion dollars in new debt is expected, of which 601 billion dollars had already accumulated in the first quarter as of 31 December 2025.

Foreign countries remain major creditors

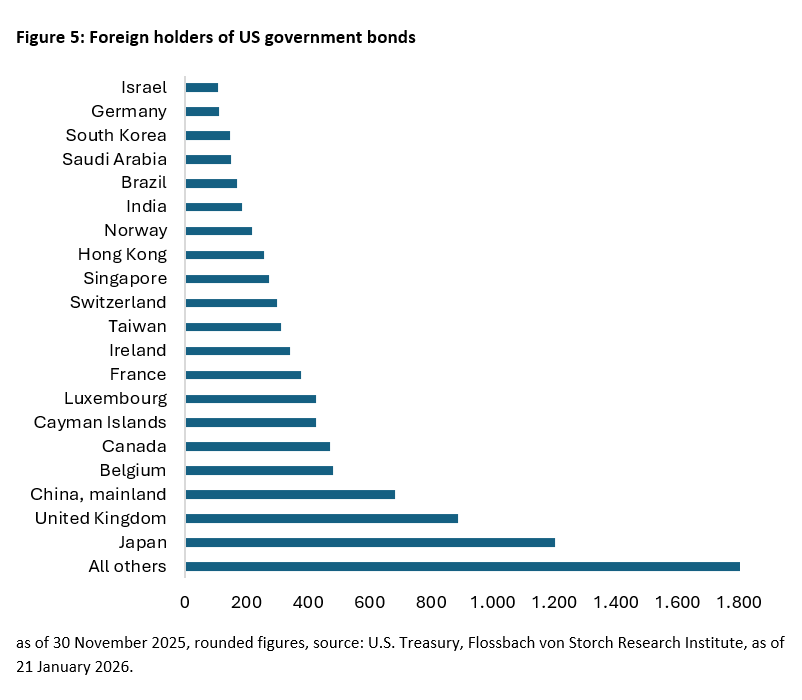

Just under $9.4 trillion, or around 31 per cent of all marketable US debt, is held abroad. The most important creditors are Japan and China, including Hong Kong. The largest European debtors, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Ireland, Switzerland, Norway and Germany, hold exactly one third of this, at just over $3.1 trillion (Figure 5).

A good $3.9 trillion, or 42 per cent of the total $9.4 trillion in foreign debt, is held by foreign "official entities" such as central banks. This includes just under $386 billion in T-bills and a good $3.5 trillion in longer-term T-bonds and T-notes. Fifty-eight per cent, or $5.5 trillion, is held by the private sector – pension funds, insurers, banks, family offices, asset managers and private investors.

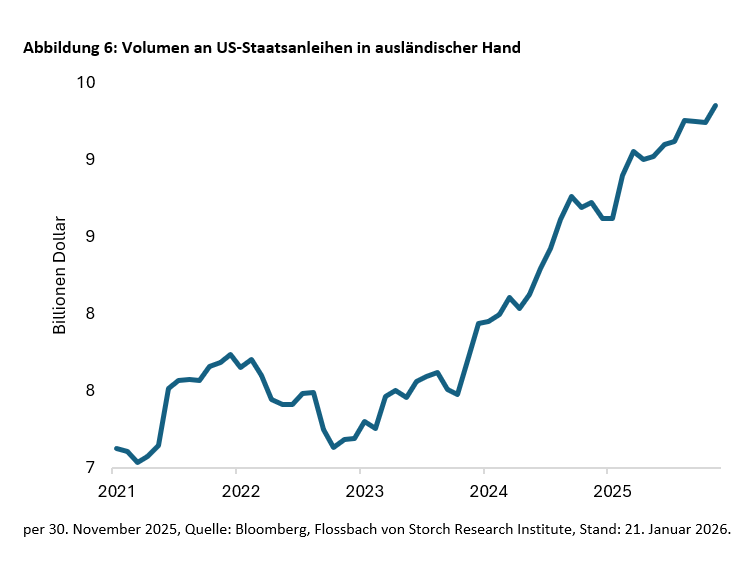

While China has significantly reduced its holdings of US Treasuries from $1,246 billion to $683 billion over the ten years from the end of 2015 to November 2025 – without any noticeable active sales, but rather through bond maturities – the rest of the world is rebuilding its holdings after a period of restraint during the coronavirus pandemic (Figure 6).

Foreign holdings currently account for a good 24 per cent of all US debt. In 2015, the figure was around 34 per cent, at its most recent low in 2023 it was around 22 per cent, and in 2002 the financing share was 19 per cent according to Bloomberg data.

Japan, which is often suspected of reducing its US holdings in order to support the yen, for example, increased its holdings by a good 140 billion to 1.2 trillion dollars last year. At the end of 2021, Japan held 1.3 trillion dollars – the highest level ever.

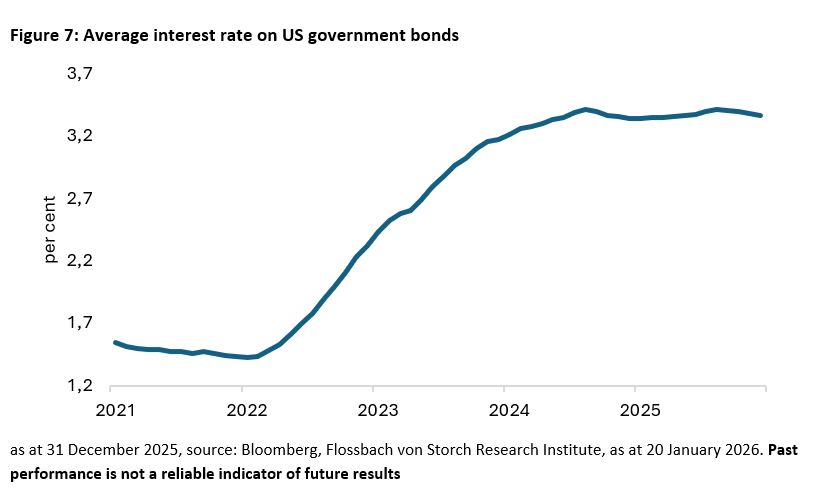

Sharp rise in interest charges

The increase in the share of foreign holdings of US debt over the past two years is likely due to the significantly more attractive interest rates in the US. The interest rate payable by the US on its marketable bonds has more than doubled since its low in 2022 (Figure 7).

As the rise in interest rates was triggered not only by debt concerns but also by the Federal Reserve's interest rate hikes, Donald Trump is attacking the US central bank, which he believes should cut interest rates significantly.

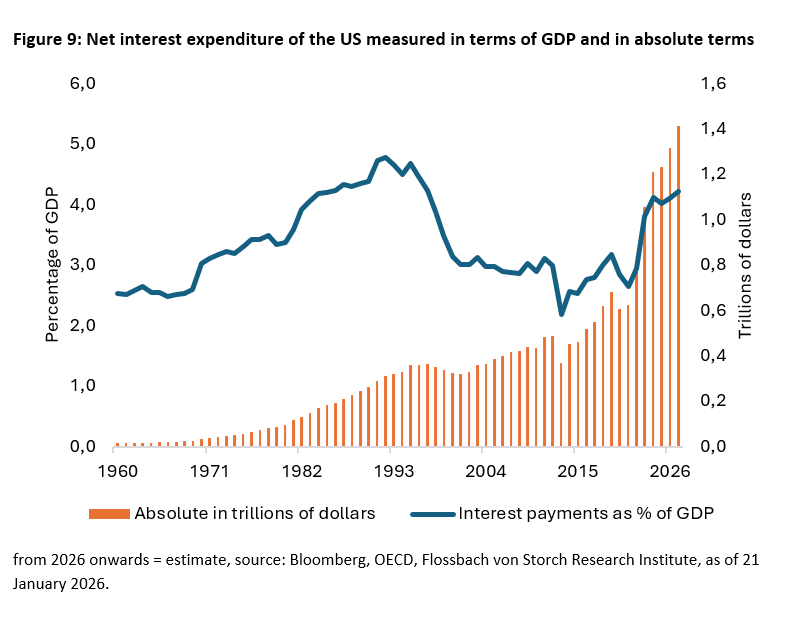

The current interest rate levels for US bonds mean an expansion of what is now the largest item in the US budget: the interest burden. The US government's net interest expenditure after collecting its own interest income amounted to a good USD 1.2 trillion in 2025 and is expected to rise to a good USD 1.4 trillion by 2027. At more than four per cent of gross domestic product, interest expenditure is approaching the 1995 record of 4.7 per cent (Figure 9).

High market liquidity for US government securities

As with other securities, liquidity, which indicates how receptive a market is, is a decisive factor in possible fluctuations in the prices of US Treasuries. The liquidity for US government bonds is enormous. In 2025, more than one trillion dollars were traded per trading day. In December, which is a month with many public holidays, the total was a good ten trillion dollars, 30 per cent of which were T-bills (Figure 10).

US securities as a "weapon"?

Do foreign countries, and Europeans in particular, with their large holdings of US government bonds, have a "weapon" at their disposal, as some commentators have suggested in response to Trump's demands regarding Greenland?

There is no doubt that Europe could use its trillion-dollar holdings of US government bonds as leverage against the US. A sell-off would drive up US interest rates enormously, making debt financing extremely expensive for the US. Even the high liquidity on the US Treasury market would probably not be enough to prevent massive distortions in prices and interest rates, especially since experience shows that liquidity dries up immediately in crises. On the contrary, there could be a chain reaction that would put considerable pressure on major asset classes such as bonds in general and equities, possibly leading to a crash. Gold could also fall significantly if investors were forced to offset losses from other asset classes by selling the precious metal. There is therefore no interest in large-scale sales of US government bonds in Europe either, especially since private investors cannot simply be forced to sell off certain investments.

But if Europe reminds the US government that it alone takes on more than $400 billion in US government debt each year and throws the possibility of a buyer's strike into the ring, it could be an ace up its sleeve in the poker game with Trump. If this is not necessary at present, it may be in the future.

The US needs capital like never before – for its government spending, but also for the frenzied appetite for credit among its technology companies. In addition, Trump wants to increase the military budget by $500 billion in 2027. This will be impossible to achieve from the budget, which is already in a dire state with a six to seven per cent deficit even without increased military spending. Loyal creditors are therefore needed, and the US should not scare them away!

____________________________________________

1 At the end of September 2024, there were just over 27.7 trillion dollars in marketable US Treasur-ies outstanding. Of these, 33 per cent (9.1 trillion) had a remaining term of less than one year, a further 35 per cent had remaining terms of between one and five years (9.8 trillion), 14 per cent had a remaining term of five to ten years (4.0 trillion), eight per cent (2.3 trillion) had a remaining term of 10 to 20 years, and a further ten per cent (2.6 trillion) had a remaining term of up to 30 years. https://www.flossbachvonstorch-researchinstitute.com/en/studies/detail/us-government-bonds-the-pressure-is-increasing

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.