STUDY. There is some evidence showing firms repatriating their incomes in the US. However, this is unlikely to happen because of the recent tariff policies.

President Trump has repeatedly made it a top priority to re-industrialize the US economy and bring jobs back from overseas. As a key instrument for this, he uses import duties. Although some evidence shows firms repatriating their incomes in the US, this is unlikely to happen because of the recent tariff policies. Also, the aggregate impact is likely to remain delusive, which lays bare contradictions in Trump’s protectionist overhaul.

The unconventional trade policy logic

The standard argument to impose tariffs is to protect domestic industry from foreign competition, preserve local jobs, and promote national economic self-sufficiency by making imported goods more expensive and thereby encouraging consumers and firms to buy domestically produced alternatives.

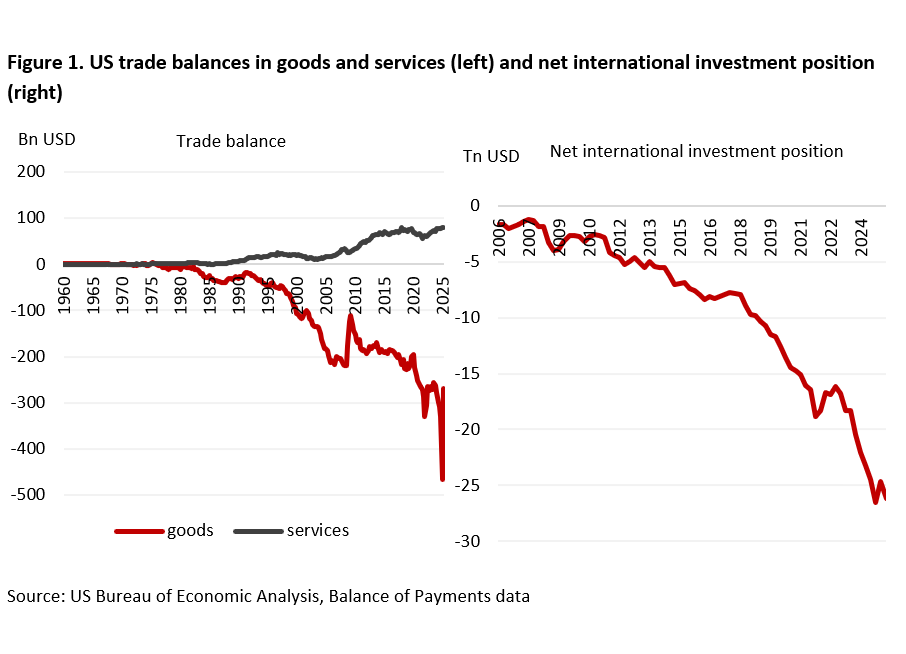

However, the logic behind Donald Trump’s tariffs goes beyond this traditional protectionist rationale. Rather than viewing tariffs merely as a defensive measure against “unfair” foreign competition, the Trump administration has framed them as a proactive industrial (and fiscal) policy tool aimed at fundamentally reshaping the US economy and global production patterns. Both U.S. and foreign companies are expected to contribute by increasing their investment in the United States and expanding domestic production. In this view, tariffs are deemed to reverse decades of offshoring driven by globalization that eventually led to “large and persistent US goods trade deficits” and a continuous enlargement of the negative net international investment position (NIIP) in the US (Fig. 1).1

This interpretation overlooks three important facts. First, as a net borrower over the past decades, US current account deficits are inevitable. Secondly, the persistent and substantial surplus in the trade of services is often accompanied by a deficit in the trade of goods.2 Instead, the US trade deficit – in aggregate and bilaterally with each partner – is erroneously interpreted not only as a data point, but as a ledger of national failure. Accordingly, it is argued by the Trump administration that the US chronically bartered away its productive capacity and industrial base for cheaper imports. The consequent economic decline allegedly became a national security issue and urged a significant rise in tariffs on a wide range of industrial goods. These tariffs are viewed as a catalyst of recent US reindustrialization efforts. Imposing them would raise domestic prices of foreign goods, nudging firms to reshore their production activities and making them re-anchor supply chains within US borders. However – and third – the decisions leading to the imposition of tariffs have never provided any proper identification of firms and industries affected, which makes it implausible to assess the extent to which the tariffs levied adequately address the underlying “emergencies.”3

A long-standing dream of reindustrialization

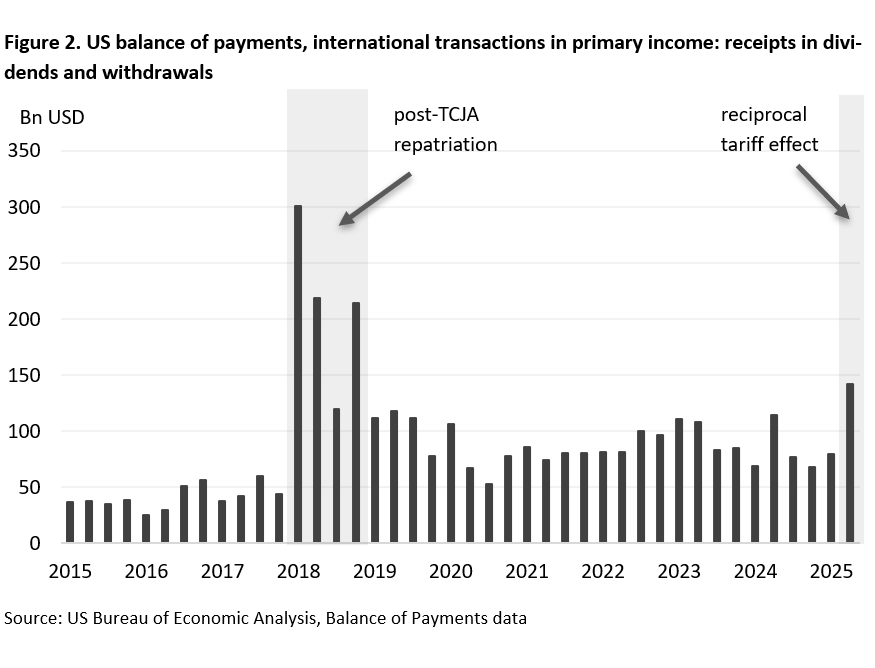

Donald Trump’s pledge of reindustrialization is not new – its policy instrument has simply changed during his second presidency. During the first Trump administration between 2017 and 2021, the focus was on tax incentives rather than tariffs. Specifically, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) shifted the previous system of worldwide taxation – that had encouraged firms to retain earnings abroad under more favorable tax conditions – to a quasi-territorial system, in which income is taxed only where it is earned and will no longer by subject to US taxes when repatriated.4 As a transition to the new system, the Act introduced a one-time “tax holiday” on the stock of corporate profits held overseas regardless of whether these funds are effectively repatriated.5 This eliminated the tax incentive to keep earning income abroad. The logic was straightforward: by lowering the cost of repatriating profits, the policy aimed to unlock offshore income and channel those funds into domestic investment, production, and job creation. While the actual reinvestment effects were mixed, this approach directly targeted the financial incentives underlying offshoring and showed a tangible effect. Balance of payments data in Figure 2 show that US firms repatriated roughly 850 billion USD in 2018, corresponding to almost 80 percent of the estimated stock of offshore earnings held at the end of 2017 (Smolyansky et al., 2019). The repatriation continued somewhat in 2019, but at a much slower pace. However, the level of repatriated dividends and withdrawals permanently increased in the period after the TCJA, compared to the pre-TCJA era.

In contrast, the current reliance on tariffs seeks to achieve the same reshoring objective indirectly, by raising the cost of foreign production rather than improving the attractiveness of domestic investment. However, tariffs tend to increase input prices for US producers, risk retaliatory trade measures, and create uncertainty for global supply chains – factors that deter rather than encourage firms from expanding production at home. Accordingly, there is no convincing evidence of a significant repatriation move by US firms (Fig. 2).

Hot air instead of homecoming?

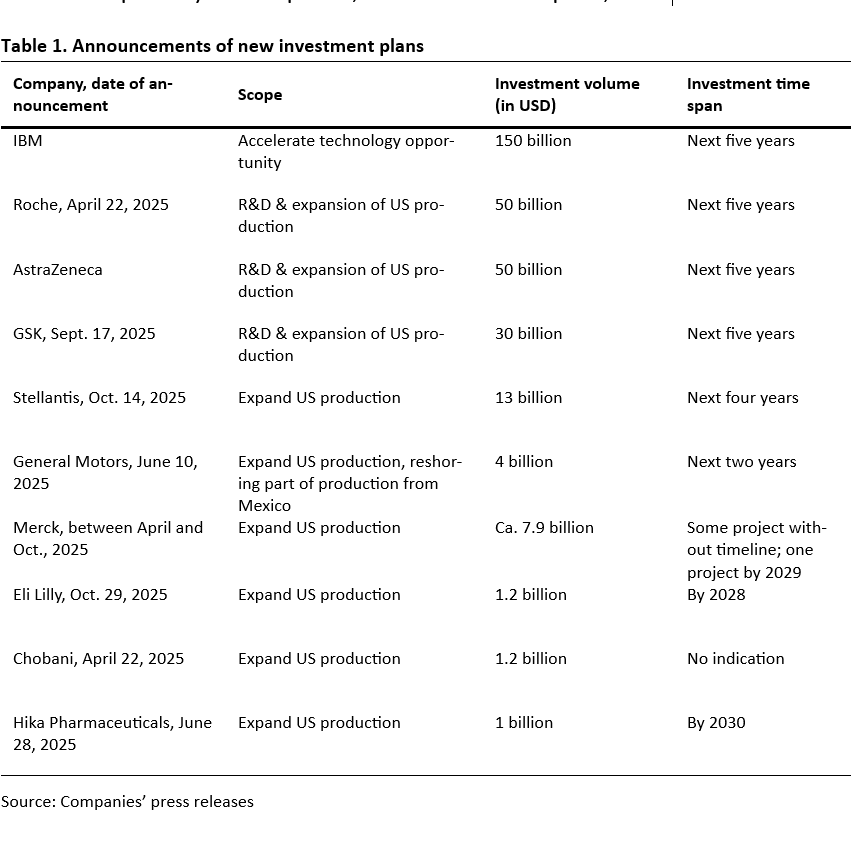

In his remarks at a summit dedicated to spurring reindustrialization in Detroit, in July 2025, the US trade representative Jamieson Greer claimed that “President Trump’s current tariff strategy is already bearing fruit”.6 As a matter of facts, there are concrete cases of companies announcing new investment projects. Among the latest announcements that provide sufficient detail, Stellantis plans to invest USD 13 billion over the next four years to expand its US manufacturing footprint by 50 percent, without, however, directly citing tariffs as a motivating factor7 In another flagship initiative, General Motors (GM) announced to invest USD 4 billion over the next two years to increase US production (in Michigan, Kansas, and Tennessee). Part of this investment is aimed at moving GM’s activities from Mexico back to the US.8 According to Greer, USD 5.5 trillion in new investment in the US has been announced so far. However, the aggregate investment volume is likely to include projects announced before April 2025 and thus not directly related to the relevant tariff announcements on and after the “Liberation Day”. Table 1 lists the main recent investment plans by US companies, announced after April 1, 2025.

From an international investment perspective, part of the announced investment projects may also reflect market-seeking and strategic asset-seeking motives rather than policy-driven reshoring. According to Dunning’s (1977, 1988) OLI framework, foreign direct investment often targets large and dynamic markets, as well as locations that provide access to technological innovation and skilled labor. Given the comparatively stronger growth outlook of the US economy and its leading position in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, it could in principle be economically rational for firms and foreign governments to expand their presence in the US market. Moreover, the broader policy environment in the United States currently provides comparatively favorable conditions for investment. Undertaken reform measures – ranging from corporate tax cuts to public-sector restructuring – have further strengthened the US investment climate. While such policies are not without controversy, they enhance the country’s relative attractiveness compared to major peers such as China, Japan, and the European Union, where structural rigidities and slower or less business-oriented (China) policy implementation continue to weigh on corporate investment decisions.

Whereas all these investment projects could have a positive effect on US production and jobs, there are reasons to be cautious not only about their link to Trump’s tariff policy, but also about their eventual outcome. Many of these announcements were already in planning stages well before the latest tariff measures and reflect broader trends – such as post-pandemic supply chain diversification, technological transitions in the automotive and pharmaceutical sectors, and incentives provided under the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act – rather than direct responses to tariff policy. No of the press releases announcing the investment plans mentions higher tariffs as the underlying reason.

Moreover, the implementation of such projects often spans several years and depends on global and domestic demand conditions, cost structures, and regulatory as well as economic policy stability. As a result, it remains uncertain whether the envisaged investments will materialize at the suggested scale, and whether they will ultimately translate into sustained increases in domestic manufacturing capacity and employment. Stellantis’ concluding note appended to its USD-13-billion investment announcement is suggestive: “Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance. Rather, they are based on Stellantis’ current state of knowledge, future expectations and projections about future events and are by their nature, subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. They relate to events and depend on circumstances that may or may not occur or exist in the future and, as such, undue reliance should not be placed on them.”9

Finally, cases of postponed or cancelled investment projects due to US tariffs are also not missing. For instance, Lucerne International decided to delay and scale down an aluminum forging project that was supposed to reshored jobs from China to Michigan. Moreover, a survey by ifo Institute suggests that almost 30 percent of German companies postponed planned US investment, and about 15 percent cancelled them, primarily due to uncertainty over US tariff policy.10

Beyond private-sector announcements, various countries have also declared investment commitments in the US. Among the major investment announcements, United Arab Emirates committed to invest in, build, or finance US data centers, Qatar announced plans to invest in technology, financial services, and energy, whereas Japan agreed to invest in various industrial sectors, including energy, artificial intelligence, electronics, critical minerals, manufacturing, and logistics.11 Yet, like corporate pledges, these are not necessarily reliable indicators of actual capital inflows, as implementation often depends on political and fiscal contingencies.

Bringing production back home is a costly balancing act

Despite the repeated pledges by the Trump administration of a reshoring boom on the horizon, it is more likely to assume that firms will remain reluctant about bringing back supply chains. A combination of high, broad-based, and randomly imposed tariffs, high labor costs, restrictive immigration policies, and economic policy uncertainty makes the decision to repatriate production a difficult balancing act.

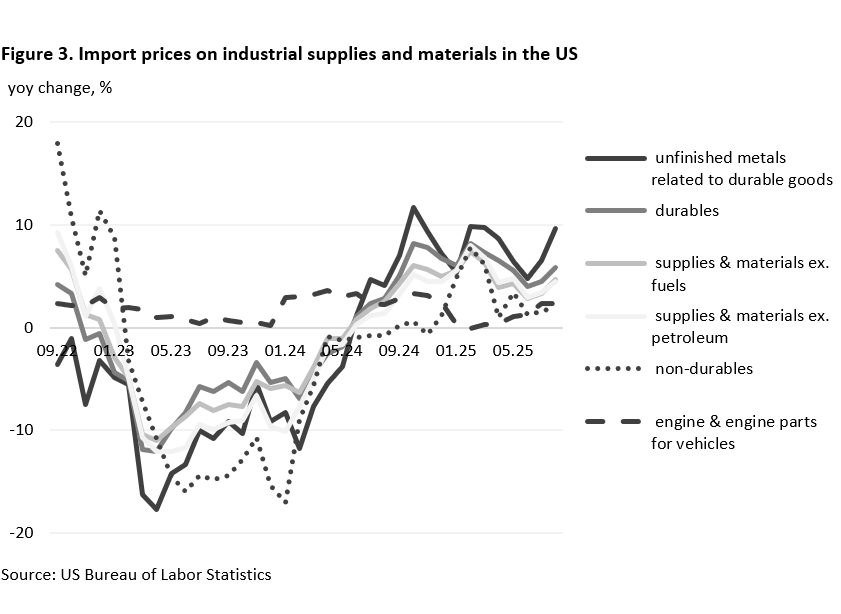

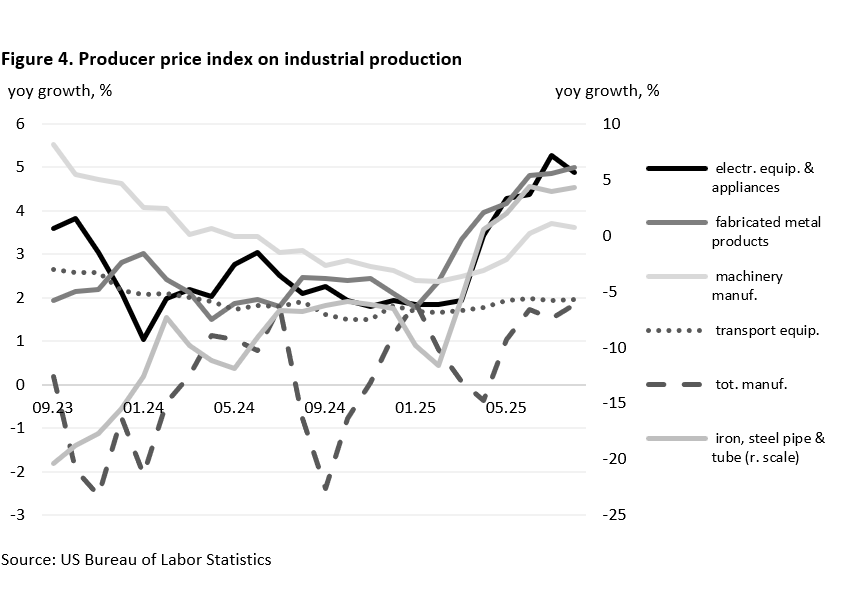

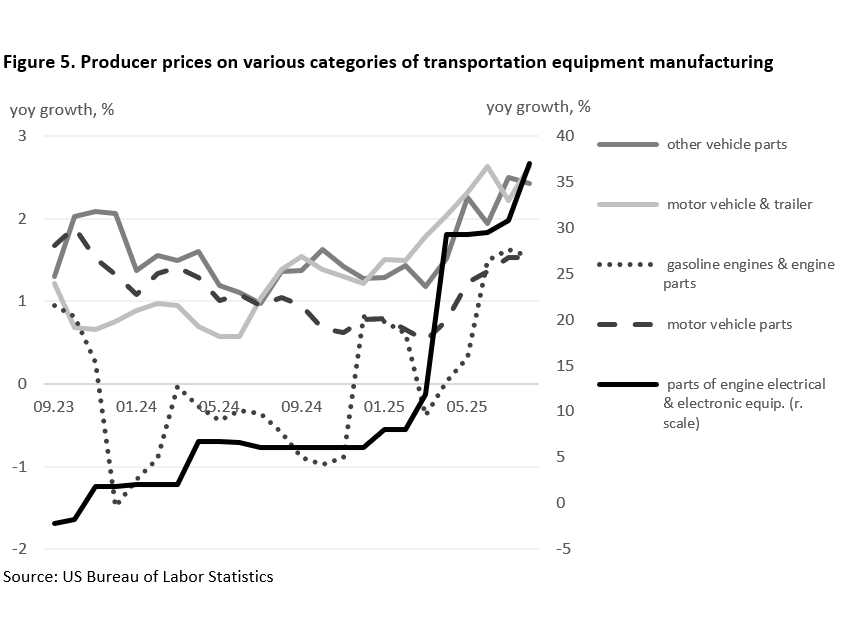

Increasing production cost that results from US tariffs on a wide range of products is probably among the biggest headwinds in reshoring decisions. Although it is still early to search for clear signs of rising import and input prices, first evidence is already telling. Import prices of certain important categories of industrial inputs have started rising in recent months, with the strongest price increases for unfinished metals related to durable goods (Fig. 3). Accordingly, dynamics of producer prices accelerated across various manufacturing activities. The most affected are manufacturing activities of electrical equipment & appliances, fabricated metal products, and iron & steel products (Fig.4). Producer prices related to the broad category of transportation equipment have remained broadly stable so far. However, producer prices of more specific manufacturing activities within this sector have been subject to significant increases since the “Liberation Day”. Prices especially on manufacturing of parts of engine electrical & electronic equipment skyrocketed after April 2025, with annual growth rates close to or above 30 percent (Fig. 5).

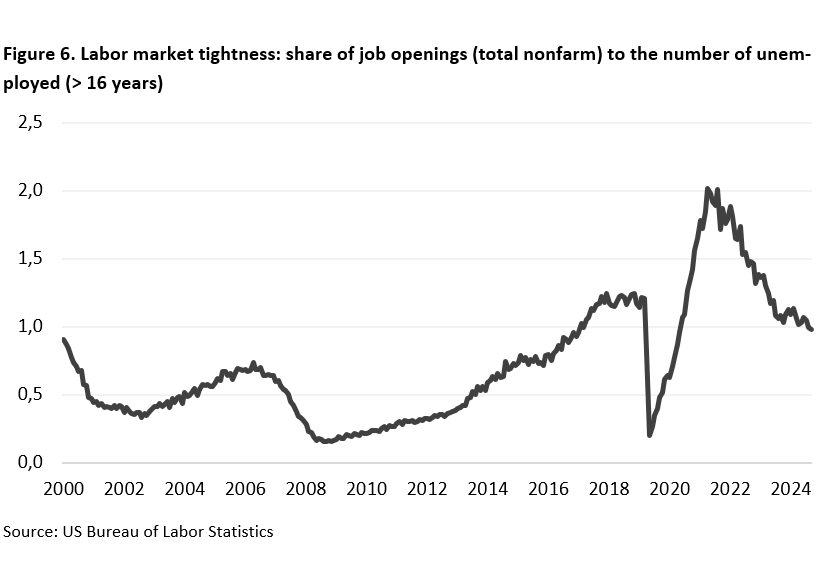

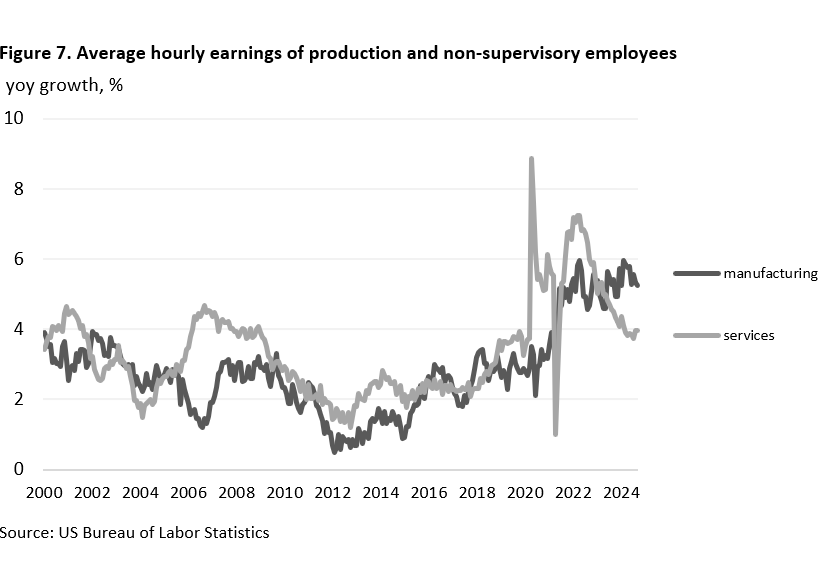

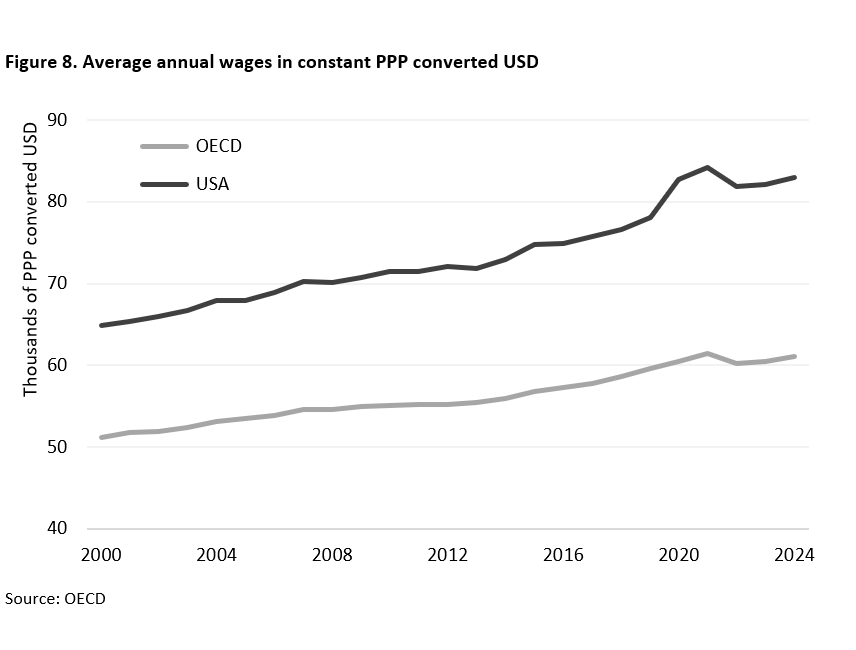

Beyond tariff-driven cost increases, also high and increasing labor costs – closely related to skilled labor shortages – are another discouraging factor for firms to reshore production to the US. Although labor market tightness declined from the post-pandemic highs, it remains above the average of the pre-pandemic period (Fig. 6). Analogously for labor costs: the annual growth rates of average hourly earnings are around 4 percent (Fig. 7) and average annual wages in the US are much higher compared to international standards (Fig. 8). Recent restrictive immigration policies – including tighter visa regulations for high-skilled workers (such as H-1B visas), increased barriers for temporary and seasonal labor programs, and reduced overall immigration quotas – are likely to exacerbate these labor market challenges by further constraining the supply of skilled and unskilled workers, thereby intensifying wage pressures and sustaining high labor costs.

Finally, in an environment of elevated uncertainty about economic policy – including unpredictable changes to tariffs, unstable trade agreements and regulatory frameworks – firms are much less willing to commit to long-term, sunk investments. This is both theoretically sound and empirically grounded. Real-options theory suggests that when irreversible costs are high and the future policy regime is unknown, the value of waiting rises and investment gets delayed (McDonald & Siegel, 1986; Pindyck & Dixit, 1994). Empirical studies support this effect: when economic policy uncertainty increases, firm-level investment and entry into export markets were found to decrease significantly (Handley & Limão, 2015, 2017; Chen et al., 2024). Moreover, when uncertainty is specifically about tariffs and trade policy the effect is even more pronounced (Koopman, 2025). Uncertainty about future tariff regimes can reduce aggregate business investment by around 2% over a year, with manufacturing investment suffering by nearly twice as much (Caldara et al., 2020).

Conclusion: Hot tariffs, cold results

In the end, tariffs may generate more political heat than industrial revival. While they make for powerful campaign slogans and headlines about “bringing production back home,” their economic reality tells a different story. Rather than fueling a broad-based reindustrialization, tariffs mostly raise input costs, invite retaliation, and amplify uncertainty – three forces that discourage precisely the kind of long-term, capital-intensive investment reshoring would require. Firms do not move factories based on presidential decrees or patriotic appeals, but on stable cost structures, skilled labor availability, and predictable policy environments. In front of high and unpredictable tariffs, instead of moving production back to the US, it would be more efficient for businesses to relocate it to lower-tariff countries. In this light, tariffs are less a lever of reshoring than a tax on business ambition: they penalize the very competitiveness they are meant to restore. If the goal is to revive domestic manufacturing, the path forward lies not in walls of protection, but in bridges of productivity, in an environment of policy stability and credibility.

References

Caldara, D., Iacoviello, M., Molligo, P., Prestipino, A., and Raffo, A. (2020). The economic effects of trade policy uncertainty. Journal of Monetary Economics, 109: 38–59.

Chen, D., Hu, N., Liang, P., & Swink, M. (2024). Understanding the impact of trade policy effect uncertainty on firm‐level innovation investment. Journal of Operations Management, 70(2): 316-340.

Dunning, J. H. (1988). Explaining International Production. London: Unwin Hyman.

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: a search for an eclectic approach. In: Ohlin, B., Hesselborn, P.-O., & Wijkman, P. M. (eds.) The International Allocation of Economic Activity. London: Macmillan Press, pp. 395-418.

Handley, K., & Limão, N. (2017). Policy uncertainty, trade, and welfare: Theory and evidence for China and the United States. American Economic Review, 107(9): 2731-2783.

Handley, K., & Limao, N. (2015). Trade and investment under policy uncertainty: theory and firm evidence. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(4): 189-222.

Hirschman, A. O. (1980). National power and the structure of foreign trade (Expanded ed.). University of California Press. (Original work published in 1945)

Kehoe, T. J., Ruhl, K. J., &Steinberg, J.B. (2018). Global imbalances and structural change in the United States. Journal of Political Economy 126: 761-96.

Koopman, R. (2025) The likely micro- and macro-economic consequences of a unilateral US trade policy. World Trade Review, 24(4):446-462.

McDonald, R., & Siegel, D. (1986). The value of waiting to invest. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(4): 707-727.

Pindyck, R. S. (1988). Irreversible investment, capacity choice, and the value of the firm. The American Economic Review, 78(5): 969-985.

Smolyansky, M., Suarez, G., & Tabova, A. (2019). U.S. corporations’ repatriation of offshore profits: Evidence from 2018. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes.

__________________________________________________

1 NIIP captures the difference between a nation’s stock of foreign assets and a foreigner’s stock of that nation’s assets. A negative NIIP reflects a debtor’s position of a country with respect to the rest of the world. While the US NIIP has long been negative, this mainly reflects the country’s attractiveness as a destination for global capital. Trump’s policy may not seek to reduce these inflows per se but to change their structure – from financial to industrial investment – thus replacing Wall Street jobs with factory jobs, in line with his domestic political narrative.

2 Besides, merchandise trade deficits likely reflect underlying structural economic changes that influence manufacturing performance. Specifically, there is evidence confirming that the loss in manufacturing jobs in the US could be mostly attributed to productivity growth (Kehoe et al., 2018).

3 The analysis in this paper interprets Trump’s tariff policy primarily as a protectionist instrument aimed at restoring domestic industrial employment. Admittedly, there is also a geopolitical reading: as Hirschman (1980) showed for Germany in the 1930s, trade policy can serve as an instrument of power. In this sense, Trump’s tariffs might be seen less as a reindustrialization strategy and more as an attempt to leverage America’s market dominance and its partners’ export dependence—successfully so with Europe, less so with China. Yet, for the purpose of this analysis, the focus remains on the economic-industrial rationale that underpins Trump’s own narrative.

4 Before the TCJA, the Homeland Investment Act of 2004 provided a temporary “tax holiday” on repatriated earnings from the statutory 35 percent to 5.25 percent for a one-year period between November 2004 and December 2005.

5 The one-time tax rate is 15.5 percent on earnings and 8 percent on reinvested income.

6 The entire speech is available at: ustr.gov/about/policy-offices/press-office/speeches-and-remarks/2025/july/ambassador-jamieson-greer-remarks-reindustrialize-summit-detroit-michigan.

7 Company’s news release from October 14, 2025.

8 Company’s news release from June 10, 2025.

9 Company’s news release from October 14, 2025.

10 Ifo Konjunkturumfrage from June 2025.

11 Both the Japan’s trade and finance ministries (https://www.mof.go.jp/policy/international_policy/convention/dialogue/251029_fact_sheet_1.pdf) and the White House (https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/10/28195/) issued a statement about the underlying investment program, but neither document offers implementation details about the funding source, timeline, and implementation stages thereof.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.