COMMENT. Large job data revisions are no proof of political bias. History points to a simpler explanation: they often occur in recessions. The latest figures may be an early warning.

Last Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published its monthly labor market report. Financial markets pay close attention, since signs of weakness could prompt the U.S. Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. While the labor market remained robust, job gains for the previous two months were revised sharply downward. In response, former President Trump dismissed the head of the BLS and accused her of political bias. A look at revision numbers since 1964 shows no systematic political bias in employment figures. Instead, major corrections typically cluster during recessionary periods. The recent downward revisions are therefore more likely a signal of labor market weakness than evidence of political interference.

Revisions Are Normal in Macroeconomic Data

By definition, macroeconomic data are difficult to compile. The economy is dynamic and emerges from the interaction of countless individuals. To capture the big picture, economists draw samples and extrapolate the results to the entire economy. The larger and more representative the sample, the more accurate the figure.

In the U.S., the BLS relies on two surveys. Households report on unemployment and employment status. Businesses report on employment, working hours, and wages. On the first Friday of the following month, the BLS releases an initial estimate. Since not all businesses have responded by then, revisions follow in the next two months, incorporating delayed submissions.

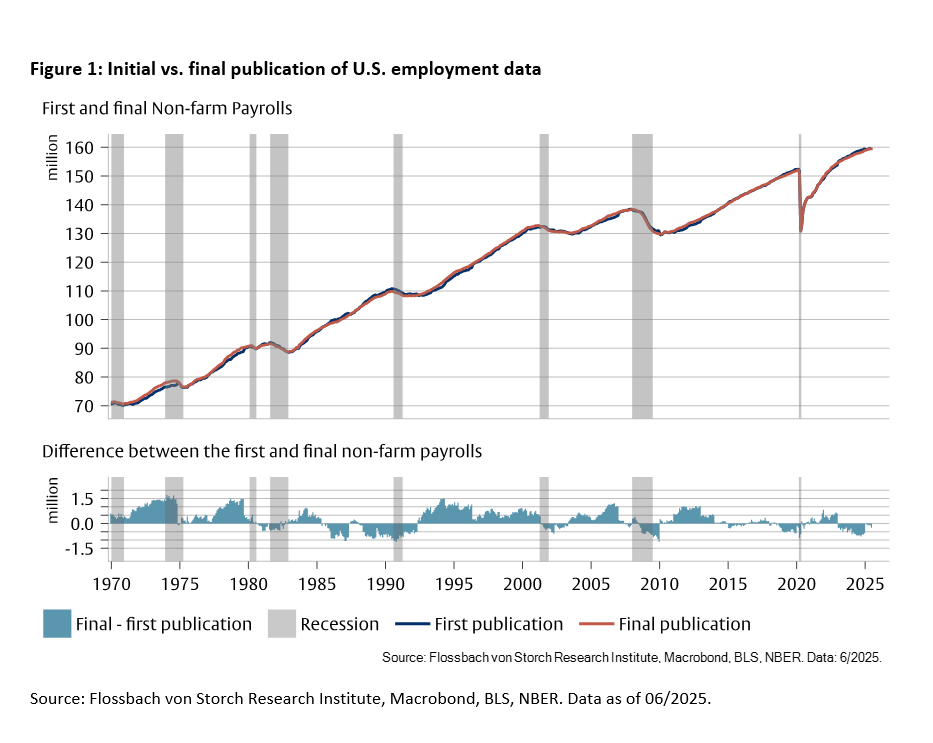

At the center is the number of nonfarm payroll jobs. This figure rises over the long term, falls during recessions (Figure 1, top panel), and is regularly revised. The difference between the final and initial estimates fluctuates with the business cycle (Figure 1, bottom panel): in downturns, preliminary reports often overestimate employment; in upturns, they tend to underestimate it and are subsequently revised upward.

The Revisions Were Larger Than Usual, But Not Exceptional

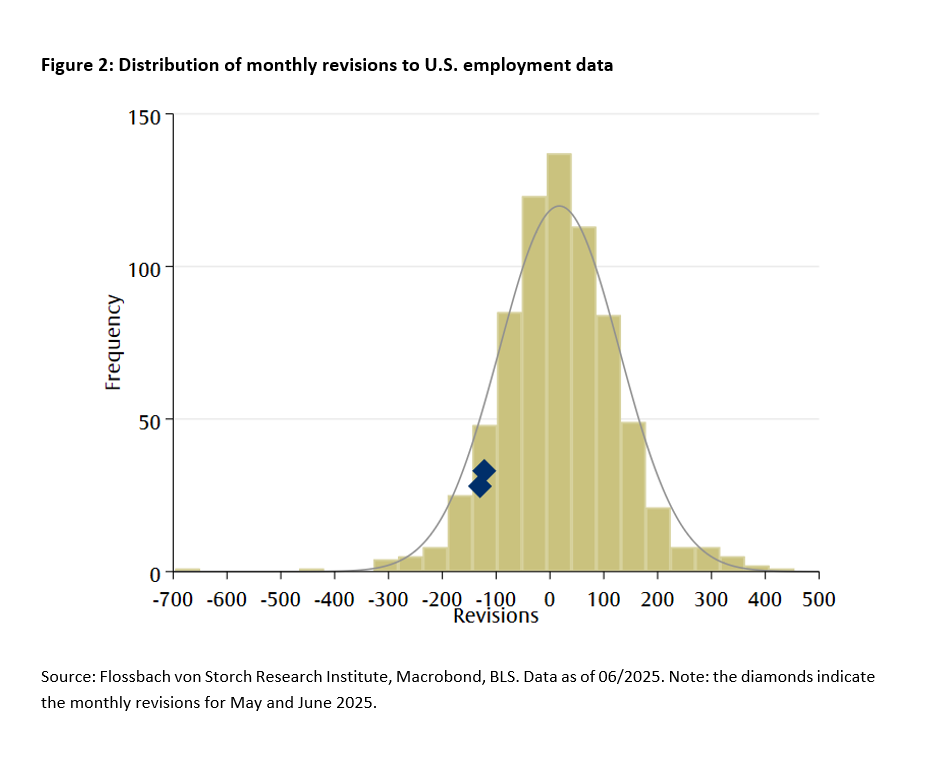

The recent downward revisions may seem dramatic, but they are within historical norms. For May, the initially reported gain of 139,000 jobs, after an interim correction to 144,000, was revised down to just 19,000. That’s a net revision of –120,000. In June, the figure dropped from 147,000 to 14,000 jobs (–133,000). These downward revisions of –120,000 and –133,000 fall between the 5th (–151,000) and 10th percentile (–117,000) of the historical distribution placing them among the weakest 7% of monthly corrections since 1964 (Figure 2). But they are not unprecedented: since 1964, more than 50 months have seen similarly large or larger corrections.

Over the long term, monthly revisions follow an approximately normal distribution. The average is +17,500 jobs, with a standard deviation of 110,000. This small positive bias is statistically significant but economically negligible. The extreme case remains the pandemic collapse in March 2020, when the final figure was 696,000 jobs lower than the initial estimate. Overall, the distribution offers no evidence of targeted manipulation.

Political Bias?

The head of the BLS was accused of embellishing the numbers ahead of the 2024 presidential election to favor the Democratic candidate Kamala Harris. That allegation is hard to verify, but a look at the historical pattern of revisions is instructive: if manipulation were possible, past BLS directors would have done the same.

Political manipulation would likely show up as systematic revisions in one direction. If the BLS wanted to favor the sitting president, it might use the uncertainty of the initial release to publish better-than-expected numbers only to revise them downward later. Conversely, if it sought to harm the incumbent, it might release worse initial figures that later get revised upward.

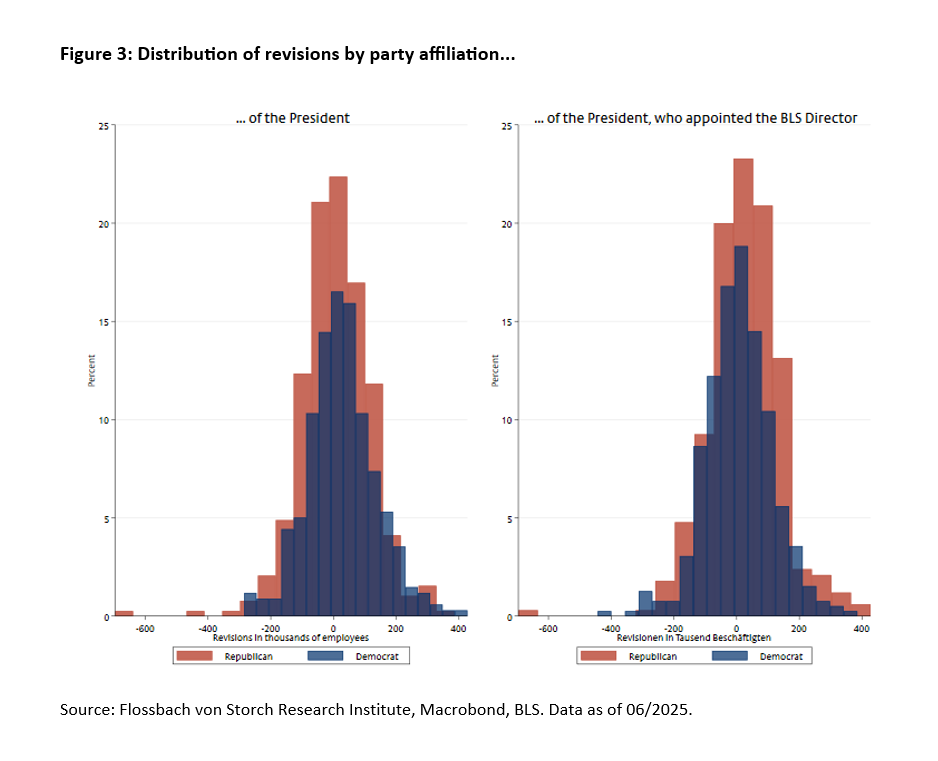

The distribution of revisions shows no significant difference based on which party is in power. During the terms of both Republican and Democratic presidents since 1964, revisions have centered around zero (see Figure 3). While the average under both groups is positive, and slightly higher under Democratic presidents, the differences are small relative to the overall variation and do not signal political manipulation. The same holds true when examining the party affiliation of the president who appointed the BLS director. When the BLS director was appointed by a Republican, the average revision was 27,000, somewhat higher than under a director appointed by a Democrat (8,700). But even this difference is too small to indicate systematic bias.

A Closer Look: When Director and President Differ

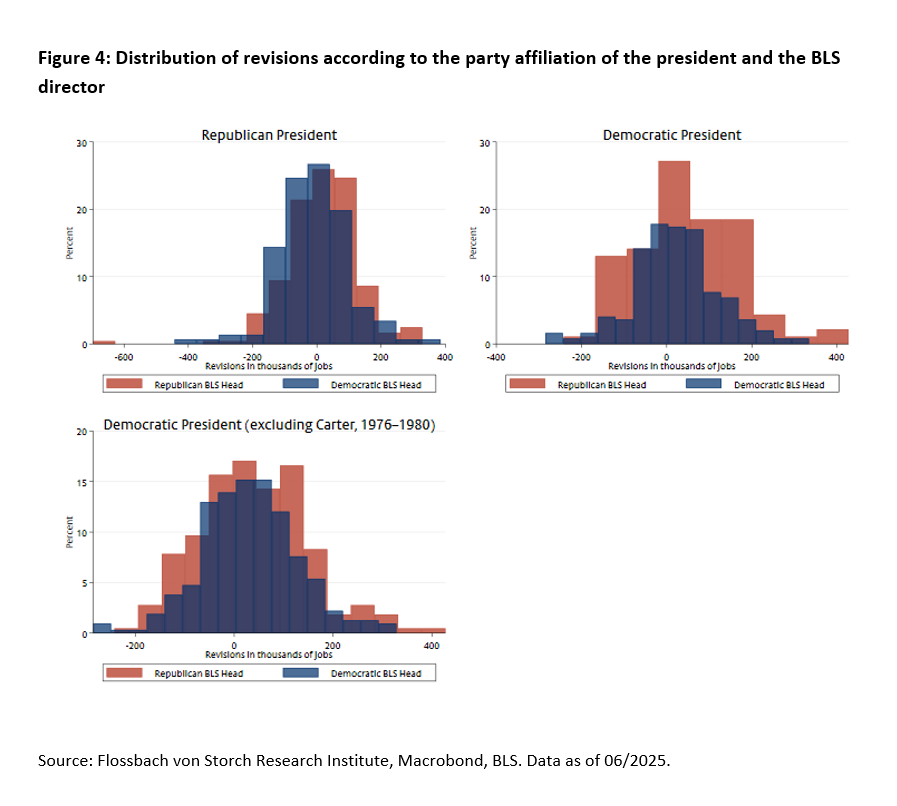

Potential biases might only emerge when the BLS director belongs to a different party than the sitting president. Under Republican presidents, it made little difference whether the BLS director had been appointed by a Republican or a Democrat (see Figure 4). Under Democratic presidents, however, upward revisions were more common when the BLS director had been appointed by a Republican.

But to conclude that Republican-appointed BLS directors tend to disadvantage Democratic presidents would be premature. The slight upward tendency in revisions is driven solely by data from 1976 to 1980, when Democrat Jimmy Carter was president. He did not appoint a new BLS director until 1979—two years into his term—and continued working with a director appointed in 1973 by Republican Richard Nixon. During that time, the U.S. economy was recovering from the 1974–75 recession. As noted earlier, job numbers are typically underestimated during such recovery phases.

There is no evidence of systematic political bias in employment data revisions. A cyclical component, however, may play a more important role. It seems plausible that in recessions, employment is initially overestimated because the full picture only emerges as delayed company responses are received. During recovery phases, numbers are likely underestimated, since rising employment is likewise captured with a lag.

Conclusion

The revision data provide no indication of systematic manipulation of U.S. employment figures in favor of either party. This strengthens confidence in American institutions. While the latest revisions were unusually large by historical standards, they were not unprecedented. Other factors should be prioritized such as the declining response rates from companies since the COVID-19 crisis, or the current economic environment. It is not uncommon for a U.S. president to replace a BLS director appointed by a predecessor. A deliberate attempt to manipulate the numbers for political gain, however, would be damaging to institutional credibility.

The correlation between recessions and downward employment revisions should not be ignored. If the recent corrections reflect economic conditions, they may offer early signs of a coming recession. Viewing them solely through a political lens could lead to a costly misjudgment.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.