However, the perception of what is precisely deemed as critical infrastructure and what risks are involved especially when giving up control over it to foreign operators differs much across countries. This could be problematic since critical infrastructures are characterized by strong transboundary interdependences and require thus cross-border cooperation. Moreover, governmental strategies related to critical infrastructures may have important geopolitical consequences. This note summarizes the existing definitions and approaches to identify and protect critical infrastructure, by focusing on the major economies across the developed world.

2. What is a critical infrastructure?

Despite a high degree of complexity surrounding the issue, there is a broad consensus in the scientific community, among experts and policymakers on the general definition of critical infrastructures. A critical infrastructure (CI) comprises a single or multiple assets or systems – physical, organizational or virtual – which are so vital for the society that any failure or degradation of their service would result in sustained supply shortages and/or a serious and undesirable impact on vital societal functions, including health, safety, security, economic or social well-being of people (OECD 2019, Alcaraz & Zeadally 2015). Accordingly, the focus is on the pivotal role that the functioning of CI plays for economic and social well-being.1

Typically, CI is identified in the national context, leading to the notion of the national critical infrastructure (NCI). In the context of the EU, European critical infrastructures (ECI) additionally accompany the framework. They “constitute those designated critical infrastructures which are of the highest importance for the Community and which if disrupted or destroyed would affect two or more MS [Member States], or a single Member State if the CI is located in another Member State” (EC 2006, p. 4).2

A distinguishing feature of critical infrastructures is the existence of interdependences between single infrastructures. They are evident in cross-sectoral dependences in the acquisition and implementation of products and services which are provided by one CI and are vital for a proper functioning of another CI (Laugé et al. 2015). Additionally, interdependences may be transboundary in nature if the functioning of a critical infrastructure in one country depends on another critical infrastructure located abroad.

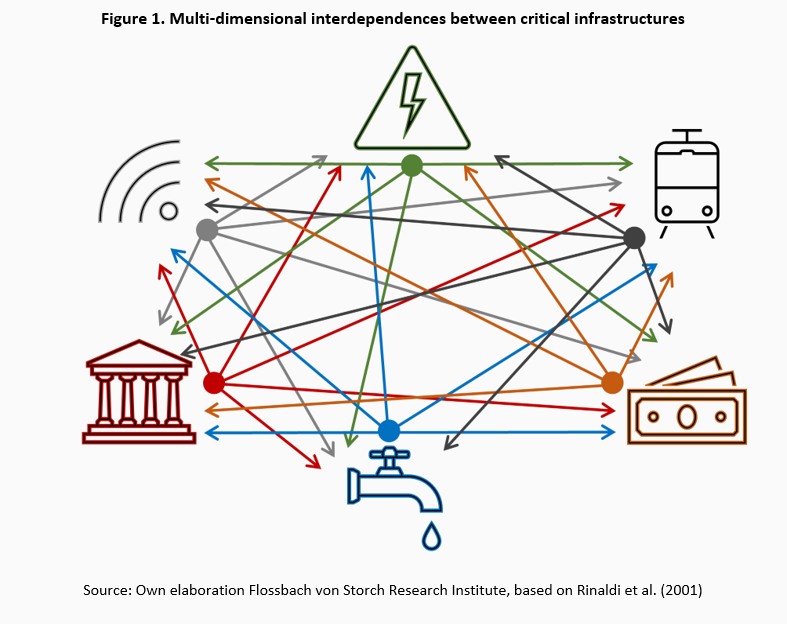

Beyond the sectoral feature, there exist four layers of interdependences between critical infrastructures (Rinaldi et al. 2001):

- physical: the operation of one infrastructure depends on the material output(s) of the other;

- cyber: dependency on information transmitted through the information infrastructure;

- geographic: dependency on local environmental effects simultaneously affecting several infrastructures located in a certain area;

- logical: any kind of dependency mechanism not characterised as physical, cyber or geographic layer, e.g. human decision-making and actions.

Since critical infrastructures are typically complex systems, multiple combinations of the four dimensions and thus multi-layer interdependences can occur between any bilateral set of CI at the same time. Figure 1 breaks down the underlying complexity in a simplified framework for the core set of six critical infrastructures – energy, water, transport, information and communication, finance, and government. Each sectoral node is bi-directionally dependent on every other sectoral node. These interdependences are channeled through all the aforementioned layers. For instance, information and communication is a critical supplier of both material outputs (networks, hardware) and information (telephone and wireless services) to all the other critical infrastructures. Moreover, this interconnectedness often goes cross-border – if, for instance, energy providers from different countries exchange relevant information. Finally, since human interactions are an indispensable part of this communication, logical layer is obviously involved.

Dementsprechend müssen kritische Infrastrukturen in einem systemischen, sektorübergreifenden und mehrschichtigen Ansatz betrachtet werden, bei dem alle Arten direkter und indirekter, physischer, virtueller, geografischer und logischer Abhängigkeiten berücksichtigt werden. Schließlich bestehen die Abhängigkeiten nicht nur innerhalb nationaler Grenzen, sondern können auch eine starke internationale Dimension haben. Daraus folgt, dass Bedrohungen nicht in einem rein nationalen Kontext bewertet werden können. Die Verflechtung der heutigen Wirtschaft - z. B. ICT-Systeme und Finanzinfrastrukturen - und Gesellschaft bedeutet, dass externe Störungen schwerwiegende Auswirkungen auf die inländischen kritischen Infrastrukturen haben können – und vice versa.

Während die Anerkennung und Konzeptualisierung von Interdependenzen, Verflechtungen und der grenzüberschreitenden Dimension in Fachkreisen weit fortgeschritten und allgemein bekannt sind, haben sie sich in der praktischen Anwendung in den Ländern und Regionen bisher weit weniger niedergeschlagen (OECD 2019).

3. Wie werden kritische Infrastrukturen klassifiziert?

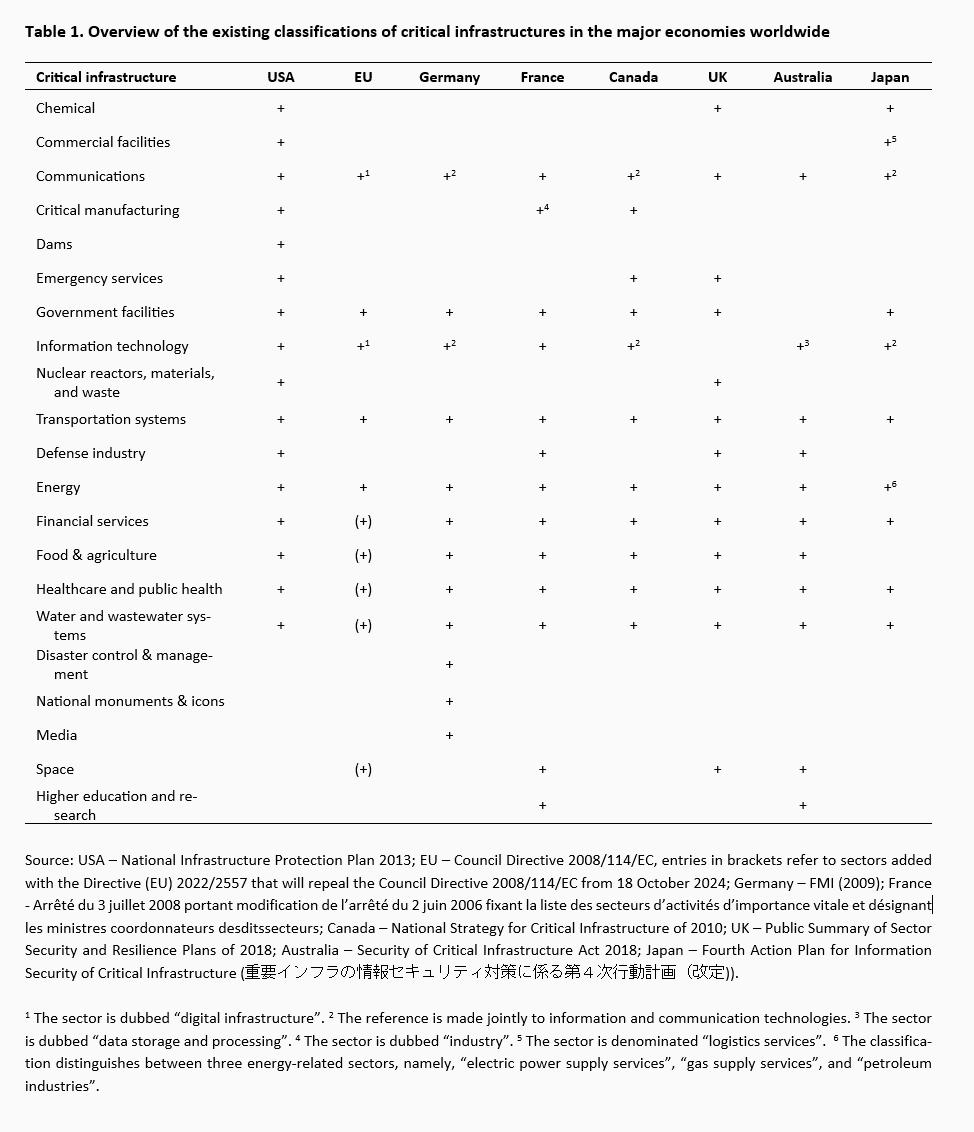

Tabelle 1 gibt einen Überblick über die bestehenden sektoralen Klassifikationen in den wichtigsten Industrieländern. Die US-Klassifizierung wird als Referenz für die sektoralen Bezeichnungen herangezogen, da die USA über den am weitesten entwickelten und umfassendsten Handlungsrahmen für kritische Infrastrukturen und deren Schutz verfügen.

Die US-Klassifikation ist nicht immer vollkommen kompatibel mit anderen Klassifikationen, und die sektoralen Bezeichnungen unterscheiden sich manchmal. So werden beispielsweise in der US-Klassifikation Kommunikations- und Informationstechnologie getrennt behandelt, während in Deutschland, Kanada und Japan diese beiden Sektoren gemeinsam als Informations- und Kommunikationstechnologien betrachtet werden.

Trotz dieser Unterschiede besteht zumindest ein Konsens über die Kerngruppe der Sektoren/Aktivitäten, die als kritische Infrastruktur bezeichnet werden. In allen Klassifizierungen gehören Energie, Verkehr, Kommunikation, Informationstechnologie, Nahrungsmittel, Gesundheit, Wasser, Finanzen und Regierungsdienste fast eindeutig zu den kritischen Infrastrukturen. Andere Sektoren sind eher länderspezifisch. Dies betrifft so scheinbar wichtige Sektoren wie Verteidigung, Chemie, kommerzielle Einrichtungen, kritische Produktion, Staudämme, Notdienste und den Nuklearsektor.

In einigen Ländern wird bei der Klassifizierung von Sektoren mit kritischen Infrastrukturen die Hauptverantwortung einer bestimmten Behörde oder eines Ministeriums zugewiesen. In den USA beispielsweise fällt jeder Sektor in den Zuständigkeitsbereich einer bestimmten sektorspezifischen Agentur (Sector-Specific Agency, SSA), bei der es sich um ein Bundesministerium oder eine andere Regierungsstelle handelt. Die wichtigste Einrichtung in diesem Sinne ist das Ministerium für Heimatschutz (Department of Homeland Security), das für 10 von 16 kritischen Infrastrukturen zuständig ist. In der EU verlangt die jüngste Richtlinie (EU) 2022/2557 von den Mitgliedstaaten die Benennung von Behörden, die für die ordnungsgemäße Anwendung und Durchsetzung der in der Richtlinie festgelegten Vorschriften zuständig sind, sowie von einheitlichen Ansprechpartnern, die die grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit gewährleisten.

An important challenge within the EU for a functional coordination and effective protection of critical infrastructures is that countries differ much in defining, identifying, and managing critical infrastructures. An extreme example constitutes Italy where no CI strategy or programme exists nor is there any lead institution in charge of critical infrastructures (OECD 2019). Similarly, Portugal limits its CI policy coverage to two sectors – energy and transport – as identified in the Council Directive 2008/114/EC.

These differences in classifications and deficiencies in the underlying strategies often reflect national preferences and specific perceptions of priorities or the lack thereof. However, due to transboundary interdependences between critical infrastructures and, accordingly, the need of cross-border cooperation, efforts to better align and harmonise approaches across countries is an indispensable risk management strategy.

4. The blind spots in the recent CI policies

Two main problems in the past experience of CI protection can be identified. First, the negligence of transboundary interdependences between critical infrastructures results in a weak cooperation in setting a robust CI risk management framework. Second, industrial policy strategies of the major developed countries have been so far often inattentive in considering geopolitical implications of trade and cross-border investment strategies involving domestic critical infrastructures.

Regarding the cooperation issue, the strategies to date have been fragmented, limited to localized inter-governmental initiatives. The most institutionalized one is known as the Critical Five, established in 2012 by five developed economies, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US. The aim of the initiative was to enhance information sharing and work on issues of mutual interest. The efforts put so far have been of a conceptual nature, directed towards finding a common understanding of critical infrastructure (Critical Five 2014) and of the links between infrastructure investment, economic growth and prosperity in the framework of the Critical Five initiative (Critical Five 2015).

Within the EU, efforts have been made to strengthen both internal and external cooperation. A promising step to advance the internal cooperation is given by the Directive (EU) 2022/2557 that will shape the relevant framework from 18 October 2024. However, based on the past experiences with the adoption of the predecessor Directive 2008/114/EC, difficulties with establishing an effective cooperation practice cannot be excluded. This assumption is in so far realistic that the ultimate responsibility for national security is in the hands of single member states rather than at the EU level and the incentives to cooperate have been often limited. Regarding the external cooperation, it has involved neighbouring countries of the EU and countries of the European Economic Area (Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein) as well as other countries in Europe and beyond. However, most of the initiatives involved mere informal cooperation, workshops and expert meetings with a vaguely specified exchange of best practices, as well as efforts – of Germany with Russia – that obviously failed due to misjudgement of risks related to pursuit of imperialist ambitions. An exception here regards the cooperation within NATO, which has recently led to a detailed scrutiny of current security challenges in critical infrastructures of energy, transport, digital infrastructure, and space (EU/NATO 2023). This notwithstanding, a much more far-reaching and outcome-oriented toolkit for cooperation is still lacking (Lazari & Mikac 2022).

Regarding the missing sensibility to geopolitical issues in the CI protection, it can be traced back to the past industrial policy strategies conducted in the global framework of liberalization of cross-border flows of goods, services and production inputs, including technological knowhow and information. The prevailing paradigm of free markets and open economies was unconditionally applied to a vast range of sectors, irrespective of their CI status. This often resulted in the foreign acquisition of assets also in CI sectors, with sometimes substantial shifts of ownership abroad. This process extensively happened in the EU, but also in other developed economies, the US included.

Among the major acquirers, Chinese investors were intensively involved in taking over CI entities. On the sectoral level, China strongly invested in port infrastructure worldwide, with important European port terminals now partially or fully owned by Chinese operators (Jüris 2023, Geinitz 2022). Also Chinese investment in US communication and information technologies proceeded inexorably during the 1990s and 2000s (Hillman, 2021). Finally, China is carving out a niche as the preferred provider of information and communications infrastructure to developing countries. Beijing currently intensifies efforts to sell communication satellites across the global South. The Chinese digital giant, Huawei, is currently active in more than 170 countries. Two other Chinese technology companies, Hikvision and Dahua, supply around 40% of surveillance cameras worldwide. Finally, Hengtong Group is among the four main global suppliers of submarine cables, which channels over 95% of international data transfer (Hillman 2021).

This process of intensifying FDIs and trade relations was for a long time perceived as an integral part of the democratization of non-democratic countries, ideologically motivated by change through trade as well as the liberating effect of communication technologies and open cyberspace (Gehringer 2023, Hillman 2021). However, with intensifying authoritarian tendencies particularly evident in China’s government style of Xi Jinping, geopolitical risks become non-negligible for countries giving up their control over critical infrastructures to Chinese entities. This is driven by the evidence that China’s centralized and party-led political system blurs the distinction between commercial, political and military interests (Jüris 2023, Cristiani et al. 2021). The authoritarian lead of the China’s Communist Party (CCP) explicitly regards the alignment of interest of the state and of private companies as a central strategy in the achievement of national strategic goals. The latter obviously involve domestic industrial policy targets, but, additionally, often expand beyond China’s national borders (Gehringer 2023).3 Accordingly, internationally oriented Chinese companies are instrumental in expanding the CCP influence abroad and – more precisely – in modernizing the People Liberation Army through technology transfer (Jüris 2023, Hillman 2021). This strategy is in so far enforceable that numerous companies in China are state-owned or – if allegedly private – under a strong influence of the CCP, via the CCP-affiliated management members. Moreover, internationally active companies are often financially incentivized and operationally supported to contribute to the achievement of China’s strategic goals.

With the growing recognition of risks associated with unconditional liberalization of cross-border economic relations – baked by more frequent spying and cyberattacks incidents – governments, especially in developed countries, started revisiting their industrial policies and pursuing a de-risking approach, particularly if involving critical infrastructures and entities.

Among the first movers in this regard was Washington, with intelligence officials warning in a congressional report from 2012 that Chinese tech infrastructure could jeopardize the US networks.4 In 2019, the Federal Communication Commission banned carries from device purchases from Huawei and ZTE.5 The US warnings regarding the aforementioned risks are in the meantime well-perceived by other governments of Australia, Japan and several countries in Western Europe.

Despite a substantial delay, the EU has recently revisited its strategy towards China. In the “Strategic Outlook” Joint Communication from March 2019, the EU declared to continue dealing with China simultaneously as a partner for cooperation and negotiation, an economic competitor in pursuing technological leadership and a systemic rival in promoting alternative governance models (EC 2019). Moreover, in the context of cross-border relations, the EU put a brake on undesirable transactions and investment practices. In spring 2019, the Community adopted a regulation establishing a new pan-EU investment screening framework for FDI review. Although the regulation is criticized for being a loose coordination and cooperation tool, with EU Member States being able to exchange relevant information on single foreign investments that may impact on their national security and public order, it marks a decisive step to increase awareness and catalyze the convergence of dispersed national FDI strategies (Hanemann et al. 2019). Moreover, similar measures are needed to screen other forms of direct and indirect involvement of foreign operators in critical infrastructures.

4. Conclusion

Foreign ownership of domestic critical infrastructures may bring about undesirable consequences to national security and public order. Especially China’s footprint in critical infrastructures across the developed world poses a serious risk to strategic sovereignty of involved countries. The determination of the CCP to achieve strategic national goals often implies the direct engagement and contribution of Chinese CCP-loyal entities – at home and abroad.

The process of China’s engagement in critical infrastructures abroad had begun in a regulatory and political vacuum, before governments of the leading developed countries started to raise concerns over national security issues. Although some counteractive answers have been given and strategies to protect critical infrastructure have been developed, the resulting framework is still underdeveloped and fragmented. As a consequence, security loopholes lead to further expansion of undesirable influences from China and more generally non-democratic systems.

A comprehensive and coherent framework is needed to address these risks. Regarding specifically the EU, a more active and systematic dialog is required to enhance the common understanding of critical infrastructures and their sectoral and transboundary interdependences. This should advance a framework for a regular exchange of relevant insights regarding particularly the ownership structure and other forms of risky foreign involvement in the operation of critical infrastructures. A unified EU approach on critical infrastructure might be challenging to arrive at but is a sure shield against adverse strategic rivalry.

1 Es gibt einige andere - oft von der Regierung entwickelte - Definitionen, die die Bedeutung von kritischen Infrastrukturen für das Funktionieren des Staates oder die nationale Sicherheit betonen (OECD 2019). Zu den Beispielen hierfür gehören die ehemaligen kommunistischen Länder in Osteuropa, nämlich die Tschechische Republik, Lettland, die Slowakische Republik und Polen.

2 Die Richtlinie (EU) 2022/2557 ändert diesen Rahmen geringfügig ab. Insbesondere sollte jeder Mitgliedstaat auf der Grundlage der Liste der 11 Sektoren die kritischen Einrichtungen in diesen Sektoren bestimmen. Die Richtlinie definiert den Begriff "kritische Infrastruktur" als "einen Vermögenswert, eine Einrichtung, eine Ausrüstung, ein Netz oder ein System oder einen Teil eines Vermögenswertes, einer Einrichtung, einer Ausrüstung, eines Netzes oder eines Systems, der/die für die Erbringung eines wesentlichen Dienstes erforderlich ist", klärt aber nicht die begriffliche oder praktische Verbindung zur kritischen Einheit. Nach dem Wortlaut der Richtlinie sind kritische Einheiten jedoch Betreiber einer oder mehrerer kritischer Infrastrukturen (Art. 13(1b), Art. 21(1a)). Darüber hinaus bezieht sich die Richtlinie nicht ausdrücklich auf europäische kritische Infrastruktur, sondern verlangt eine Zusammenarbeit zwischen den Mitgliedstaaten für den Fall, dass ihre kritischen Einheiten "kritische Infrastrukturen nutzen, die physisch zwischen zwei oder mehreren Mitgliedstaaten verbunden sind" (Artikel 11 Absatz 1a). Schließlich werden in der Richtlinie kritische Einheiten von besonderer europäischer Bedeutung als Einheiten bezeichnet, die "dieselben oder ähnliche wesentliche Dienste für sechs oder mehr Mitgliedstaaten erbringen" (Artikel 17 Absatz 1b).

3 Tatsächlich hat die Europäische Kommission im Jahr 2005 ein Grünbuch über ein Europäisches Programm für den Schutz kritischer Infrastrukturen mit einer indikativen und detaillierten Liste von 11 kritischen Infrastruktursektoren veröffentlicht (EC 2005). Diese Klassifizierung wurde jedoch in den nachfolgenden offiziellen Dokumenten zu diesem Thema nicht mehr berücksichtigt.

4 Solche Ziele wurden in verschiedenen strategischen KPCh-Dokumenten und nationalen Programmen formuliert, wie z. B. der Gürtel- und Straßeninitiative (BRI), Made in China 2025, China Standards 2035 oder Chinas Militär-Zivil-Fusionsstrategie.

5 "Untersuchungsbericht über die Probleme der nationalen Sicherheit der USA, die von den chinesischen Telekommunikationsunternehmen Huawei und ZTE ausgehen. U.S. House of Representatives. Verfügbar unter: https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:rm226yb7473/Huawei-ZTE%20Investigative%20Report%20%28FINAL%29.pdf.

6 "Schutz vor nationalen Sicherheitsbedrohungen für die Kommunikationslieferkette durch FCC-Programme". Federal Communications Commission. Verfügbar unter: https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-19-121A1.pdf.

Literatur:

Critical Five (2015). Role of critical infrastructure in national prosperity. Available at: https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/critical-five-shared-narrative-ci-national-prosperity-2015-508.pdf.

Critical Five (2014). Forging a common understanding for critical infrastructure. Available at: https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/critical-five-shared-narrative-critical-infrastructure-2014-508.pdf.

EC (European Commission) (2019). Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council: EU-China – A strategic outlook. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019JC0005.

EC (European Commission) (2006). Communicaton from the Commission on a European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection, available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2006:0786:FIN:EN:PDF.

EC (European Commission) (2005). Green paper on a European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection, available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52005DC0576

EU/NATO (2023). EU-NATO task force on the resilience of critical infrastructure. Final Assessment Report. Available at: https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2023/6/pdf/EU-NATO_Final_Assessment_Report_Digital.pdf.

European Council (2008). Council Directive 2008/114/EC of 8 December 2008 on the identification and designation of European critical infrastructures and the assessment of the need to improve their protection. Official Journal of the European Union, L 345/75, available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:345:0075:0082:EN:PDF.

FMI (Federal Ministry of the Interrior of Germany) (2009). National strategy for critical infrastructure protection (CIP strategy), available at: https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/publikationen/2009/kritis_englisch.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2.

Geinitz, C. (2022). Chinas Greif nach dem Westen. Wie sich Peking in unsere Wirtschaft einkauft. C.H. Beck: München.

Gehringer, A. (2023). Calibrating the EU’s trade dependence. Survival 65(1), 81-96.

Hanemann, T., Huotari, M., Kratz, A. (2019). Chinese FDI in Europe: 2018 trends and impact of new screening policies. Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

Hillman, J.E. (2021). Chinas digitale Seidenstrasse. Der globale Kamp um die Herrschaft über die Daten. Plassen Verlag: Kulmbach.

Jüris, F. (2023). Security implications of China-owned critical infrastructure in the European Union. European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/702592/EXPO_IDA(2023)702592_EN.pdf.

Laugé, A. Hernantes, J. Sarriegi, J. (2013). Disasterimpact assessment: aholisticframework. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, pp. 730–734.

Lazari, A., Mikac, R. (2022). The External Dimension of the European Union’s Critical Infrastructure Protection Programme: From Neighbouring Frameworks to Transatlantic Cooperation. CRC Press.

OECD (2019). Good Governance for Critical Infrastructure Resilience. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Cristiani, D., Ohlberg, M., Parello-Plesner, J., Small, A. (2021). The security implications of Chinese infrastructure investment in Europe. The German Marshall Fund of the United States. Available at: https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/Cristiani%20et%20al%20-%20report%20(1)%20Updated.pdf.

Rinaldi, S.M., Peerenboom, J.P., Kelly, T.K. (2001). Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies. IEEE Control Systems Magazine, p. 11-25.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2026 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.