15.03.2023 - Studies

The dependency ratio measures the ratio of children and pensioners to the working-age population. In Germany, it has been rising since the 1990s. This is endangering our prosperity.

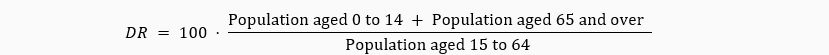

The United Nations defines the dependency ratio (DR) as the ratio of children and pensioners to people of working age per hundred. It applies:

In a first approximation, this can be used to describe demographic change and economic performance of a society. Ceteris paribus, the higher the dependency rate, the lower the economic performance per capita.

Germany benefited until the early 1990s from declines in birth rates in the 1970s ("Pillenknick") and spent this demographic dividend with full hands. Since then, however, increasing life expectancy has ensured an increase in DR (increase in the population over 64 years is no longer compensated by decrease in the population aged 0-14 years). In the next few years, the retirement of the baby boomer cohorts with high birth rates will reinforce this trend, as figure 1 shows. Globally, a turning point has also been reached.

Since the economic output needed to finance this rests on fewer and fewer shoulders, while the number of dependents is increasing in relative terms, the pay-as-you-go social systems are becoming overburdened. Waiting lists for doctor's appointments or a place in an old people's home are only two manifestations of this development.

Equally worrying are the effects on industry associated with a rising DR. If skilled workers are scarce, companies will move abroad. This is followed by a reduction in the attractiveness of Germany as a location for the remaining skilled workers and highly qualified immigrants. The feedback loop sets in motion a downward spiral.

In addition, there is a threat of higher inflation rates for consumer goods in the long term, as fewer goods can be produced in relative terms and wages rise due to the scarcity of labour. Higher real interest rates put pressure on assets.

Possible ways out are to increase productivity, which requires investment in physical and human capital, and immigration of highly productive skilled workers. To avoid national bankruptcy, a financial trade-off between spending on climate and social policy and investment is unavoidable. In addition, the immigration of qualified workers must be regulated and promoted by an internationally competitive law.

The DR, as the ratio of children and pensioners to people of working age, increases with a relative increase in the number of young or old people in a society and decreases if the number of people of working age increases. It is therefore influenced by the fertility rate. The course of the two curves for Germany since 1950 can be seen in figure 2.

After the end of the Second World War, the so-called baby boomers initially formed many high-birth cohorts. Between 1965 and 1975, however, the birth rate dropped from about 2.5 children per woman to less than 1.5 children. It has only recently risen above this level again.

As the baby boomers increasingly entered working age, the DR consequently fell continuously between 1970 and 1990. Although life expectancy was already rising at that time, the increase did not offset this effect. The share of the population that can contribute to value creation increased and there was a demographic dividend. This caused prosperity to rise continuously and probably led to a certain carelessness and the belief that this would continue forever. The fact that there would soon be a permanent reversal of the trend was either overlooked or simply refused to be acknowledged. Instead of adapting the social systems to ageing, unemployment, which had grown due to high wage increases, was fought by early retirement of older workers. In this way, a moderate, short-term relief of the unemployment insurance was bought by a heavy, long-term burden on the pension insurance.

But in 1985, DR reached its tipping point and began to rise. The baby boomers had had fewer children themselves. There was an increasing lack of working-age people, the denominator of DR. At the same time, rising life expectancy steadily increased the number of pensioners. The number of children was slightly declining, as figure 3 shows.

From 2020 onwards, the retirement of the baby boomer generations will again dramatically increase the rate of increase. The burden of generating prosperity will remain on fewer shoulders.

In a globalised world, Germany could hope to participate in the "demographic" dividends of other economies by investing abroad, at least for a while.

However, since the other major economies of the world are also no longer expected to pay "demographic" dividends, the potential success of such a strategy is fundamentally limited. If we look at the DR of the USA, China and Japan, we see that these economies have now also reached the demographic turning point (see figure 4).

China in particular, winner and driving force behind the globalisation of the last 30 years, is in danger of ageing. The demographic effects of the one-child policy are making themselves felt. Moreover, productivity gains from integrating the rural population into the labour market and copying Western technology are increasingly exhausted.1 Only in less developed countries like India or on the African continent has the demographic turning point not yet been reached. Whether this positive circumstance is enough to offset the demographic pressure of the world's largest economies, however, remains questionable.

Therefore Germany would do well to look inwards in coping with demographic change. We need to reduce DR and increase our productivity. In the following, we examine three possible solutions for their effectiveness:

The attempt to increase the birth rate through financial incentives, such as the recent increase in child benefit in Germany2 or concessionary building loans for parents, as in other European countries3, has various factual and temporal dimensions. The influence of financial incentives on birth rates seems fundamentally positive in the long term, but the interplay particularly with cultural factors remains complex. A short-term stimulation of the birth rate is not to be expected from an expansion of incentives.4 However, a study by the Ifo Institute in 2005 shows that a child born in 2000 has a balance of 76,900 euros for Germany's fiscal balance sheet over its entire lifetime. This means that society receives more back through taxes and social security contributions than it spends.5 However, the surplus naturally only arises in adulthood when people take up employment. Higher birth rates thus counteract demographic change. However, the positive effects can be expected in 25-30 years at the earliest.

An increase in the retirement age and an associated increase in the working-age population has already been decided by politicians in Germany (while in France a smaller increase is being fiercely contested). However, if one looks at the difference between life expectancy and actual retirement age in Germany, one has to doubt that the adjustments will be sufficient. Figure 5 shows the rising overall life expectancy at age 65 in recent years.

Although the actual retirement age is also rising, the difference remains essentially constant. With the number of pensioners rising in the future (cf. figure 3), it becomes apparent what burdens still lie ahead for the pay-as-you-go state pension, health and long-term care insurance. The situation is aggravated by the fact that the "hidden" reserves of people between 55 and 64 who are basically capable of working have largely been lifted in recent years, as figure 6 illustrates.

The federal subsidy to the statutory pension, however, continues to rise, and politicians cannot be expected to make drastic cuts for fear of the increasingly ageing electorate. Active policymaking beyond what is absolutely necessary from an economic point of view is not to be expected - the dithering around the double halfway line, the catch-up factor and the level of security in the statutory pension should suffice as proof of this thesis.6

Migration policy remains in search of a solution that is effective in the short term and at least potentially implementable politically. In concrete terms, this means promoting the influx and integration of qualified professionals and preventing the (permanent) departure of well-educated (young) people.

Unfortunately, the events of the last 20 years resemble a tragedy. For example, Germany still lags in terms of net immigration from abroad in an international comparison, as the comparison with Canada in Figure 7 shows.

In Canada, there are about seven foreign immigrants per 1000 inhabitants per year. In Germany, the figure is significantly lower. In Germany, we are far from the 400,000 immigrants demanded by the head of the employment agency Scheele7, as figure 8 shows:

In addition, immigration in Germany is predominantly into the social systems. If the net migration of a total of plus 4.35 million people in the years 2014 to 2021 is adjusted for the number of protection seekers of 2.3 million,8 this also results in only 250,000 immigrants per year in this time interval. In 2020, the employment rate of refugees five years after arrival stood at 55 per cent, with only 20 per cent of women in employment. The decline in employment among later cohorts is striking. Three years after arrival, only 27 per cent of the 2016 cohort were employed. This compares to 32 per cent in the 2015 cohort and 36 per cent in the 2013/14 cohort.9 The negative trend suggests that Germany is increasingly overburdened with integration (into the labour market).

However, attracting highly qualified skilled workers from abroad is only one side of the coin. It would be just as important not to lose skilled workers trained in Germany to foreign countries. This fails either. Between 2010 and 2018, an average of 132,000 Germans emigrated per year.10 The net emigration of German citizens, i.e. emigrants minus returnees, amounts to 27,000 annually. In the years from 1991 to 2018, this added up to 758,000 more emigrants than returnees. The problem is that these are well-educated skilled workers, some of whom are turning their backs on Germany for more than just a temporary period. In the IT sector in particular, emigrants return less frequently than in other sectors.11 The positive effects that a stay abroad limited to a few months or years can bring are then absent. The main reasons for emigration are higher salaries and better use of one's own qualifications.

Along with the skilled workers, companies are slowly but surely disappearing from Germany. The business location is becoming desolate. This does not only affect large corporations. Start-ups and family businesses are also finding it increasingly difficult. The head of Bayer's pharmaceuticals division, Stefan Oelrich, is one example of harsh criticism of the framework conditions. He describes Europe as "innovation-unfriendly" and adds:

"We are really shifting our commercial footprint and the resourcing of our commercial footprint much away from Europe."12

Dr Martin Brudermüller, Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors of BASF, has similar words of warning:

"Let's look at Europe first. The region's competitiveness is increasingly suffering from overregulation. It also suffers more and more from slow and bureaucratic approval procedures and, above all, from high costs for most factors of production."13

Both companies see better general conditions for the distribution of their products and for research and development in China and the USA. BioNTech's announcement that it will build a research centre in Cambridge (Great Britain) also fits in with this.14

A study by ZEW for the Family Business Foundation, which assesses the competitiveness of individual countries from the perspective of major family businesses, paints a bleak picture for Germany. Overall, Germany ranks 18th out of 21 countries surveyed. This puts us well behind Sweden and Denmark, EU member states from northern Europe. But Poland and the Czech Republic also leave Germany behind. We share the lower places with France, Spain, and Italy.15 For comparison: in the same study from 2006, Germany was still in 9th place. Since then, we have lost international competitiveness, especially in the fields of "regulation" and "energy". The development of today's leader, the USA, from seventh place in the first edition of the survey, took the opposite direction.

The poor handling of demographic change is particularly evident in the topic area of "labour costs, productivity, human capital". Here, Germany is only in 19th place in 2022. Canada, an industrialised country with a mature immigration mechanism, ranks second (cf. Figure 7).

For those who see only lobbying by companies in pursuit of benefits and subsidies behind these statements and studies, there is another development from the KfW Start-up Monitor: The start-up rate, i.e., the number of start-ups in relation to the labour force, is declining. In Germany, it has fallen from 2.76 percent to 1.17 percent since 2002. KfW notes a declining desire for professional self-employment and a disappearance of the entrepreneurial spirit. This is explained particularly by the ageing society, which for various reasons brings with it a structural decline in the desire for self-employment.

The remaining founders are particularly dissatisfied with the reporting obligations imposed on them.16 They mirror the dissatisfaction reported by large and family businesses about high regulatory density. A second point of concern for both family businesses and founders: the level of education. According to the ZEW, the front-runner in terms of the "educational level" of the working-age population is Canada. More than 60 percent of the working-age population have a tertiary education. Germany ranks 17th with 30.9 percent. According to KfW, founders in Germany complain about the lack of entrepreneurially relevant knowledge being imparted by the education system. The neglect of the proven dual education system in Germany probably also plays a role here.

Demographic change cannot be blamed on politics. But they can be blamed for having stood idly by and allowed the resulting problems to pile up.

To counteract the consequences of ageing, the productivity of the labour force would have to be increased. This requires investments in physical and human capital as well as the immigration of highly productive people. However, there is a lack of funds for investments, as they continue to be used to finance the social security funds. Climate policy forces special write-offs on the existing capital stock and the immigration of above-average productive workers is slowed down by rigid regulations, rampant bureaucracy and a deterrent tax and contribution burden.

1 The great demographic reversal, Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan, palgrave macmillan, 2020.

3 Birth rate: Countries want to spark a baby boom with these incentives - WORLD

4 Does family policy affect the birth rate? | Family Policy | bpb.de

5 The fiscal balance of a child in the German tax and social system (ifo.de), page xvii

7 Shortage of skilled workers: Why highly qualified people go abroad (wiwo.de)

8 Flossbach von Storch Research Institute, Macrobond, Federal Statistical Office and Federal Office for Migration and Refugees

9 Five years of "We can do it" A balance sheet from the perspective of the labour market (iab.de), Figure 4.1 and 4.2

10 The Global Lives of German Migrants - Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course, page 46f

11 The Global Lives of German Migrants - Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course, page 78 and Table 4-2

12 Bayer shifts pharma focus away from 'innovation unfriendly' Europe | Financial Times

15 Laenderindex-2022_Study_Foundation-Family Businesses.pdf

16 KfW Start-up Monitor 2020 Chart 1 and Table 7

02.01.2020 - Society & Finance

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch AG. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch AG remains solely with Flossbach von Storch AG. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch AG.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch AG.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.