22.02.2019 - Studies

Membership in EMU keeps Greece locked in deflationary debt and cost reduction, with which it cannot cope, despite all well-intended structural reform.

After he had defeated the Roman army in two battles in 280 and 279 BC King Pyrrhus of the Greek state of Epirus “replied to one that gave him joy of his victory that one other such victory would utterly undo him. For he had lost a great part of the forces he brought with him, and almost all his particular friends and principal commanders.” 1

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras could have said the same when EU officials celebrated Greece’s exit from its eight year adjustment program last August. The devastation of the Greek economy after the completion of “adjustment” would have justified it. Instead, he joined in the celebration. Yet, there is very little hope that the Greek economy will ever recover from this victory as long as it remains trapped in European Monetary and Economic Union. For membership in EMU keeps Greece locked in deflationary debt and cost reduction with which it cannot cope, despite all well-intended structural reform.

Phase 1: A Mountain of Debt

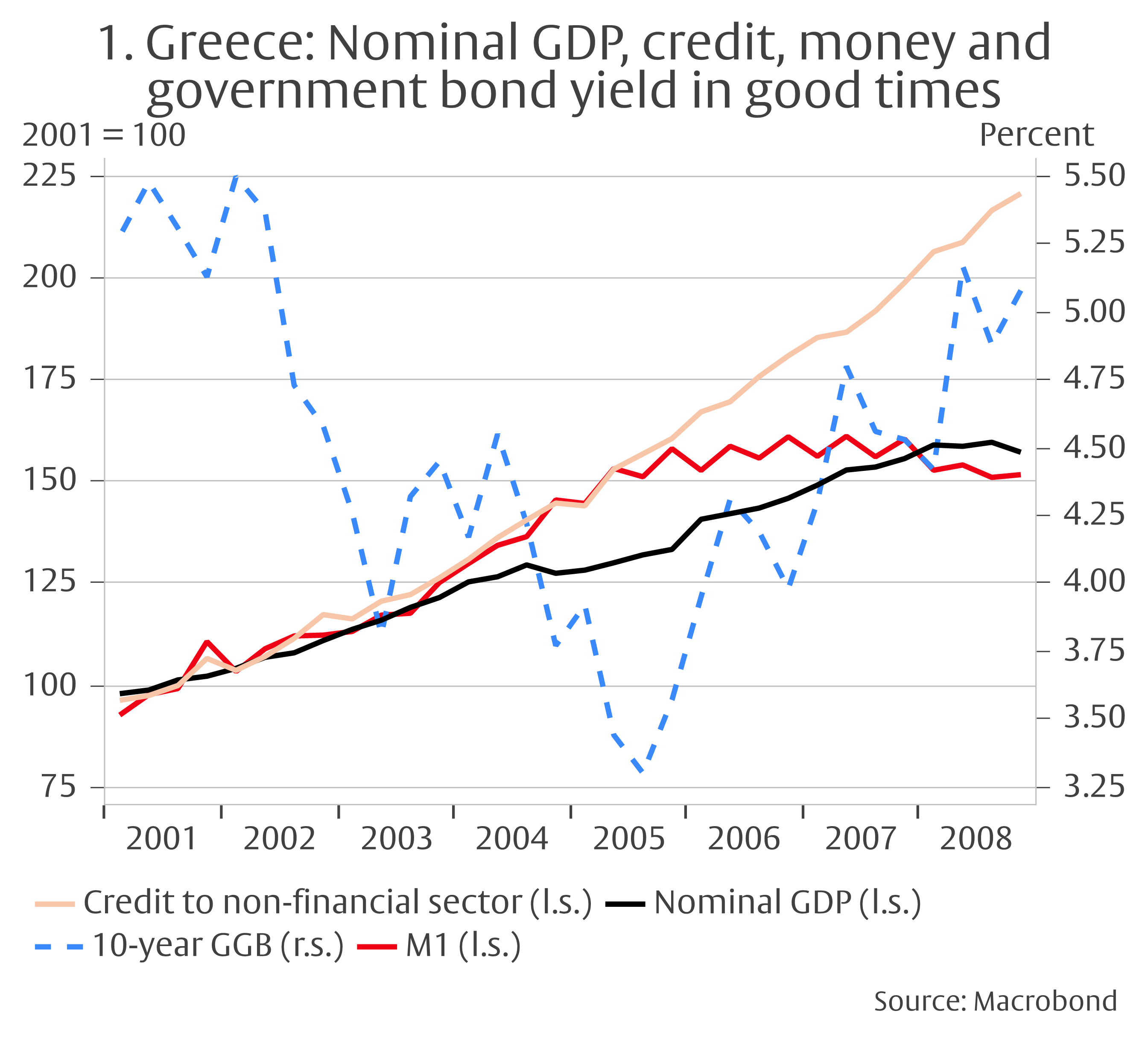

When Greece joined EMU in 2001 interest rates for private and public borrowers fell to levels never seen before by any living Greek citizen. As a result, private households, companies and the government went on a borrowing binge. Total credit to the non-financial sector more than doubled in 2001-2008, increasing by a lot more than nominal GDP (Chart 1). Interest rates increased a little in 2006, but this was regarded as a normal reaction to the cyclical upswing. However, conditions began to change in 2007 with the beginning of the financial crisis in the US. Risk premia edged up on weaker borrowers, and Greek borrowers certainly belonged to this category.

Phase 2: Deflationary deleveraging in the EMU trap

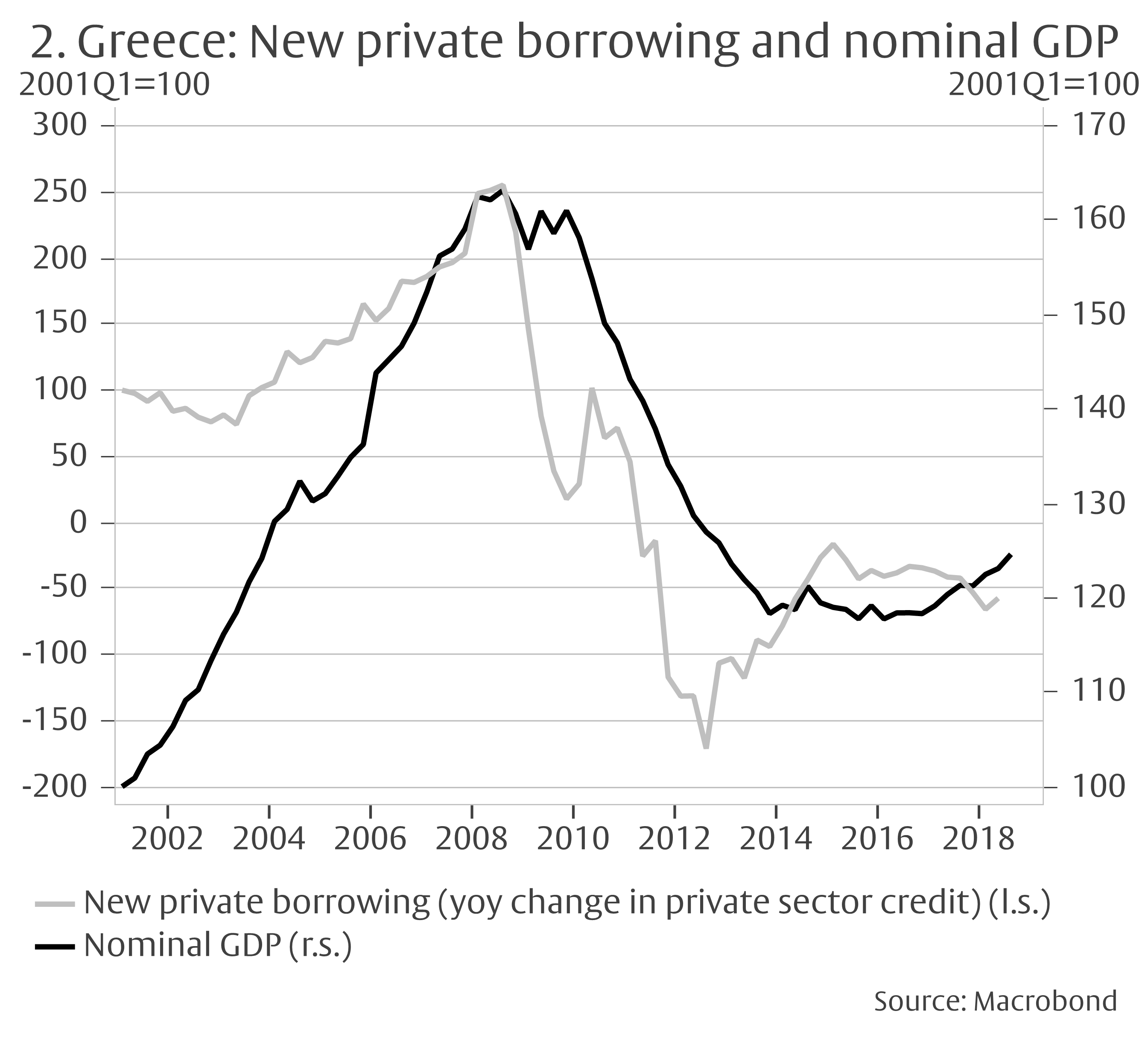

The increase in new private borrowing (calculated as the year-on-year change in private sector credit stocks) by more than 150% had helped to boost nominal GDP by 60% between the first quarter of 2001 and the third quarter of 2008 (Chart 2). However, following the intensification of the Great Financial Crisis after the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, new private borrowing began to fall, dragging down nominal GDP in its wake. Towards the end of 2009 the newly elected socialist Greek government shocked EU officials and markets by disclosing a much larger than earlier reported government budget deficit. This, and subsequent admissions that government budget deficit statistics had been forged for years to gain admission to EMU, triggered a government debt crisis, which quickly mutated into a banking crisis.

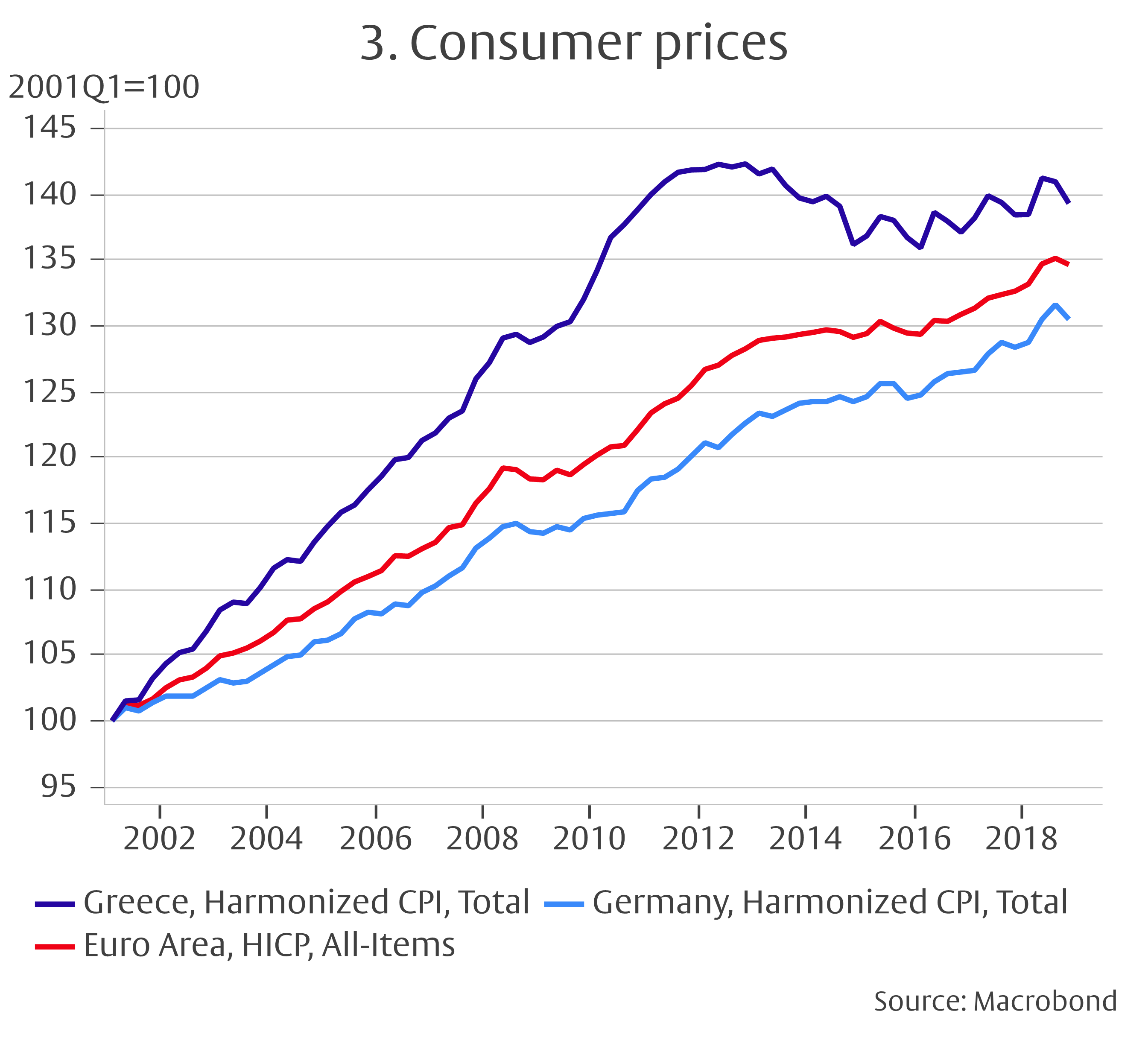

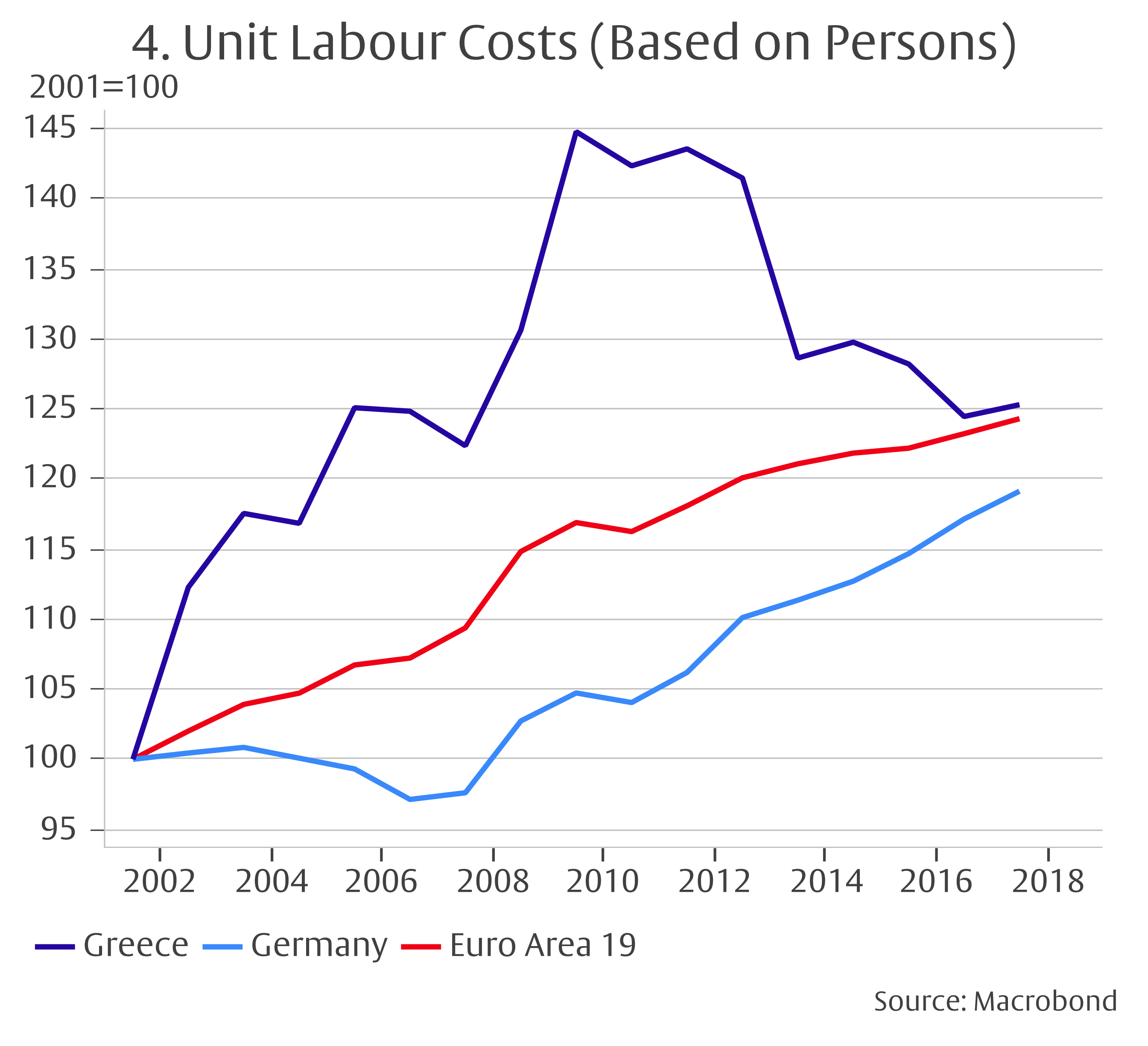

The decline in new private borrowing was briefly interrupted in the first half of 2010, when Greece received financial assistance from other euro area countries and the newly created European Financial Stability Facility (later merged into the European Stability Mechanism), but it continued thereafter. By the third quarter of 2012, new private borrowing had dropped by 167% below its peak. Although it recovered somewhat in the wake of ECB President Draghi’s famous assurance to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, nominal GDP continued to decline until the fourth quarter of 2013 to a level 27% below its peak. The continuing recovery of new borrowing helped to stabilize GDP, but it was not strong enough to return the economy to healthy growth. Hence, Greece experienced cost and price deflation (Charts 3-4).

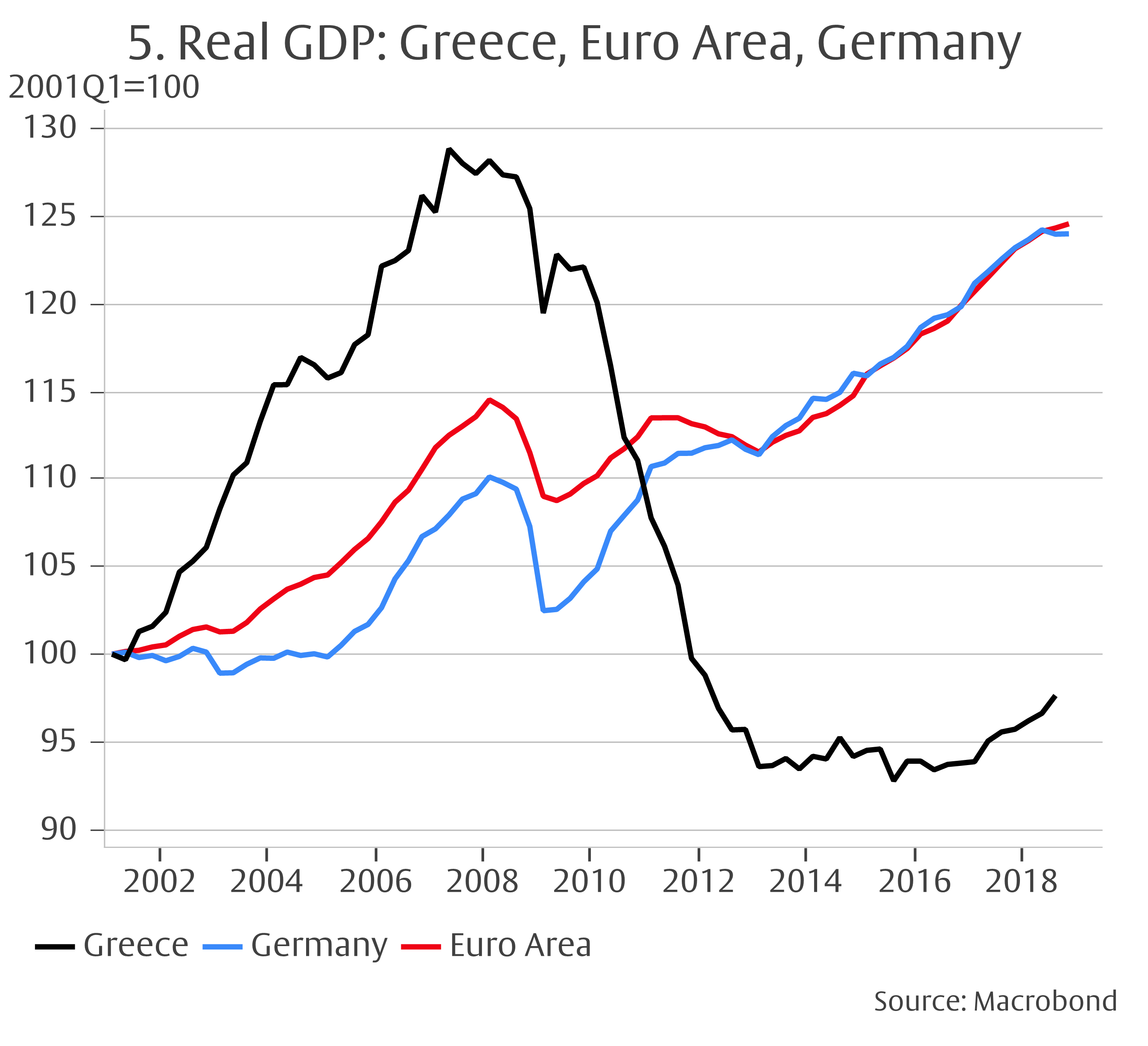

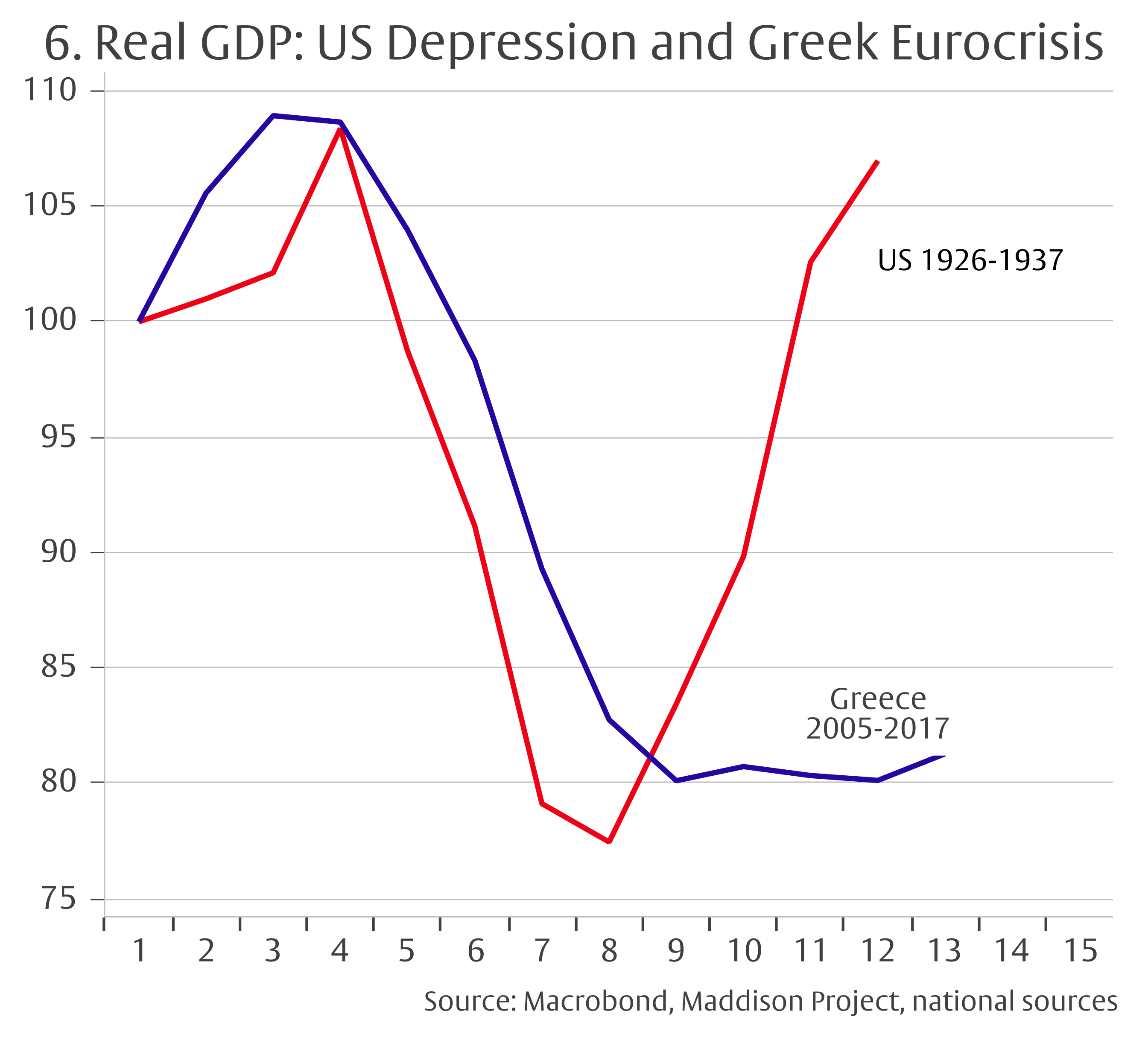

Debt, cost, and price deflation took a heavy toll on the economy. Greece did not participate in the economic recovery of other EMU countries after the Great Financial Crisis and the Euro Crisis of 2011-12 (Chart 5). Instead, trapped in EMU, Greece experienced one of the worst deflationary deleveraging crises in history. Compared to the Greek depression, the US depression of the early 1930s appears transitory (Chart 6). While it took the US eight years to get real GDP back to its pre-depression peak, Greek real GDP has remained way below its 2008 peak now for a decade. Against the background of a weakening euro area economy, prospects for the Greek economy to ever make up the losses of the past decade do not look good.

Phase 3: The illusion of “structural reform”

Few countries have been able to escape deflationary deleveraging and cost reduction without money printing and currency devaluation. Latvia is one example. Radical and front-loaded cost and debt deflation combined with a high degree of economic flexibility set the state for the subsequent recovery of the economy.2 Greece followed a different script. Policy makers neither allowed it to escape the monetary straightjacket of the currency union nor did they accept radical debt reduction. Instead, they pressed for “structural reforms”. The idea was to build a new economic environment able to attract investors creating new jobs and incomes so that the economy could grow out of its debt burden and overcome its cost disadvantages. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that they overestimated the ability of the Greek people to reinvent itself.

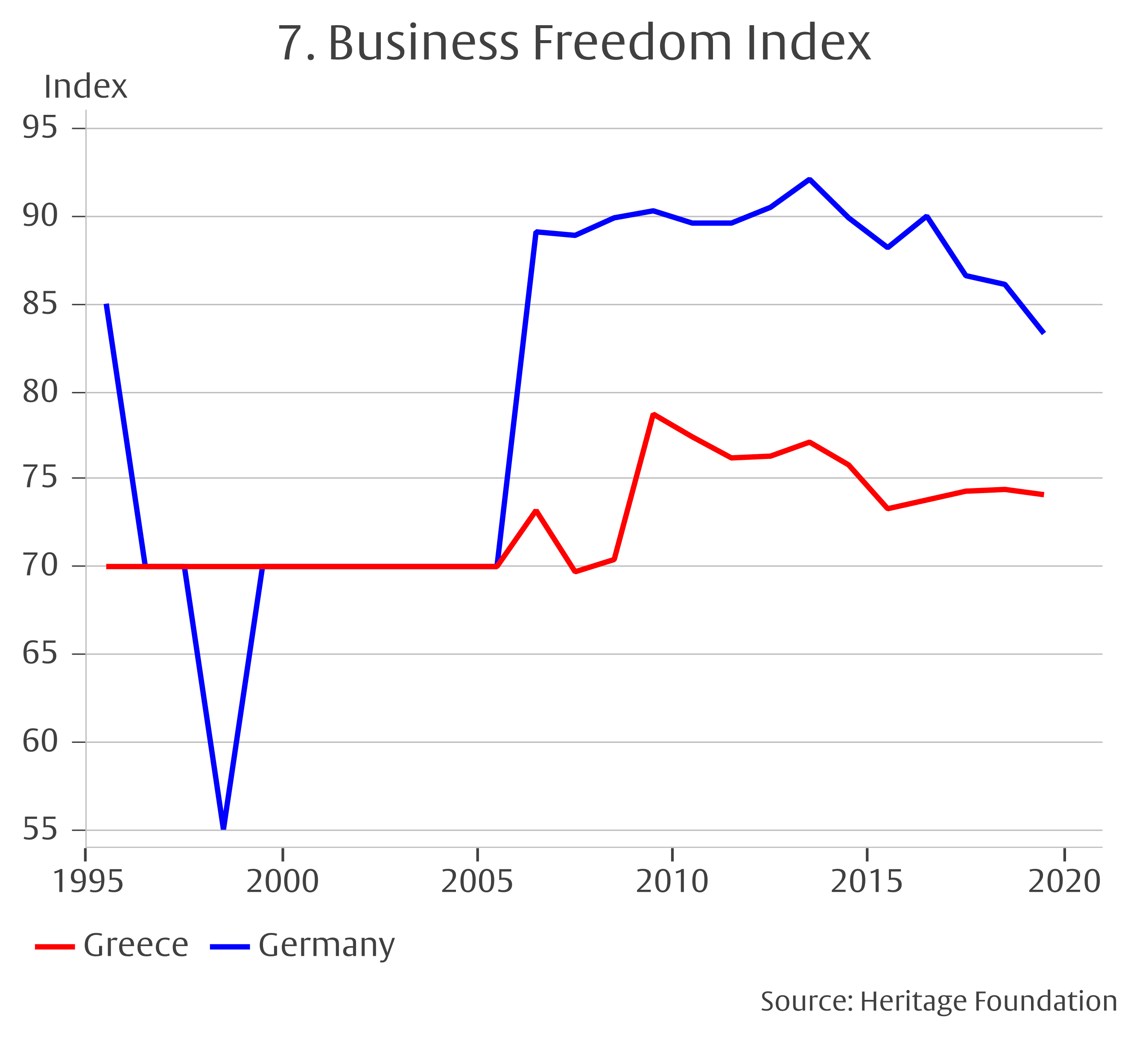

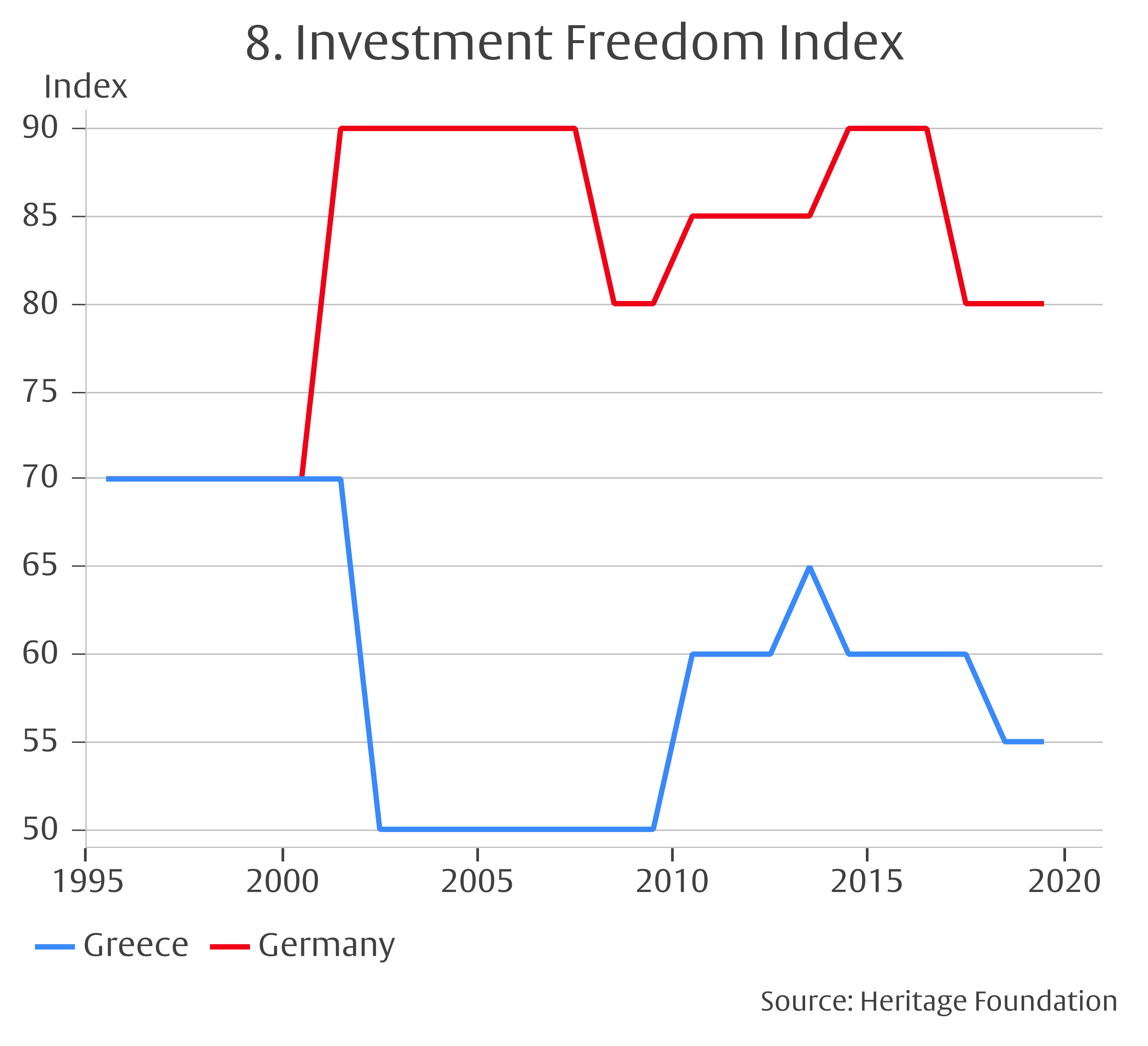

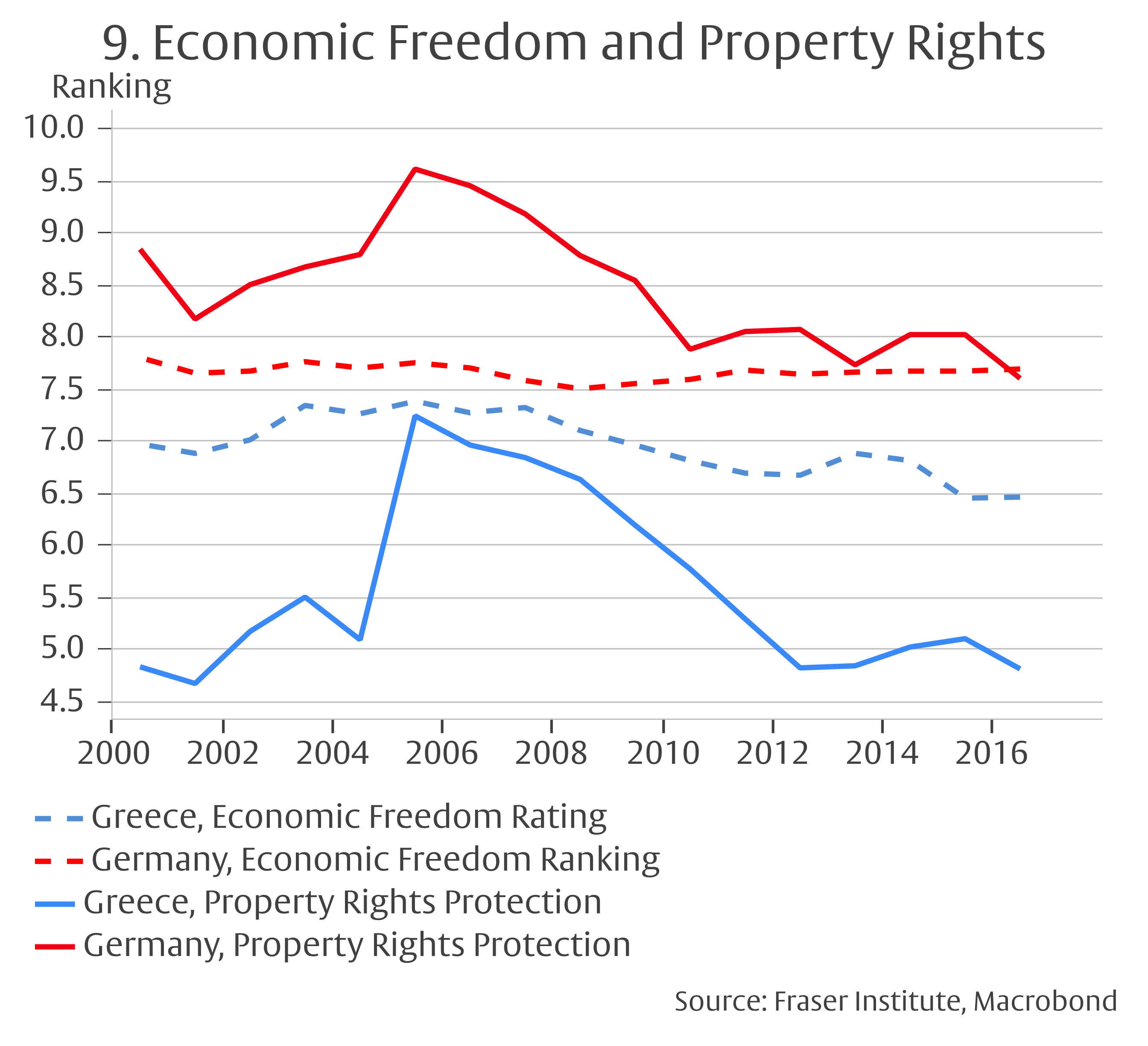

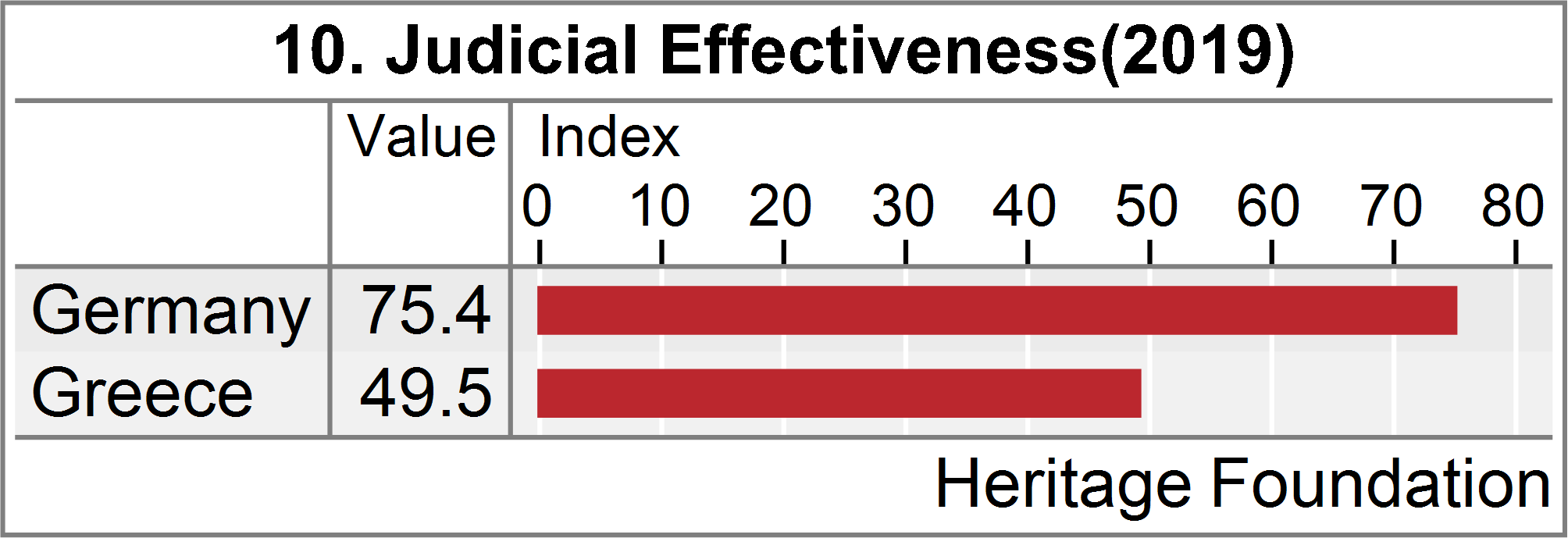

Charts 7-10 show a number of indicators comparing the attractiveness of Greece for new investments to Germany. With numerous countries in EMU and the world more attractive than Germany as a business location, the benchmark is not very high. Yet, Greece falls even short of that. Businesses in general and investors in particular enjoy less freedom; property rights are weaker; and judicial effectiveness is lower than in Germany. To overcome its severe handicaps in the form of excessive debt and high costs, Greece would need to offer big advantages for business investors. In reality, however, it is still disadvantaged.

Locked in depression

Despite huge external financial assistance and many years of efforts of reform Greece has not escaped depressionary debt and cost deflation. The meagre growth of 2017-18 will probably peter out in the looming euro area recession. The conclusion is both inevitable and sad: as long as Greece remains locked in EMU its economic future looks bleak.

1 Plutarch, The Life of Pyrrhus (quoted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrrhic_victory).

2 See Michael Biggs and Thomas Mayer, „Latvia and Greece: Less is more“, Centre for European Policy Studies (Brussels) 12 February 2014.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch SE. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch SE remains solely with Flossbach von Storch SE. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch SE.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch SE.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.