06.03.2019 - Studies

The current 719 billion Euro batch of so-called targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), which maintain cheap refinancing conditions to commercial banks in the euro area, will mature between mid-2020 and early 2021.

Were TLTROs to expire or become more expensive, the interest margins of banks – especially in Southern Europe (Italy and Spain) – would be negatively hit and the credit impulse would weaken. Hence, given the weakening economic momentum, the ECB has little choice but to extend the (T)LTROs.

Unconventional long-term funding with a southern bias

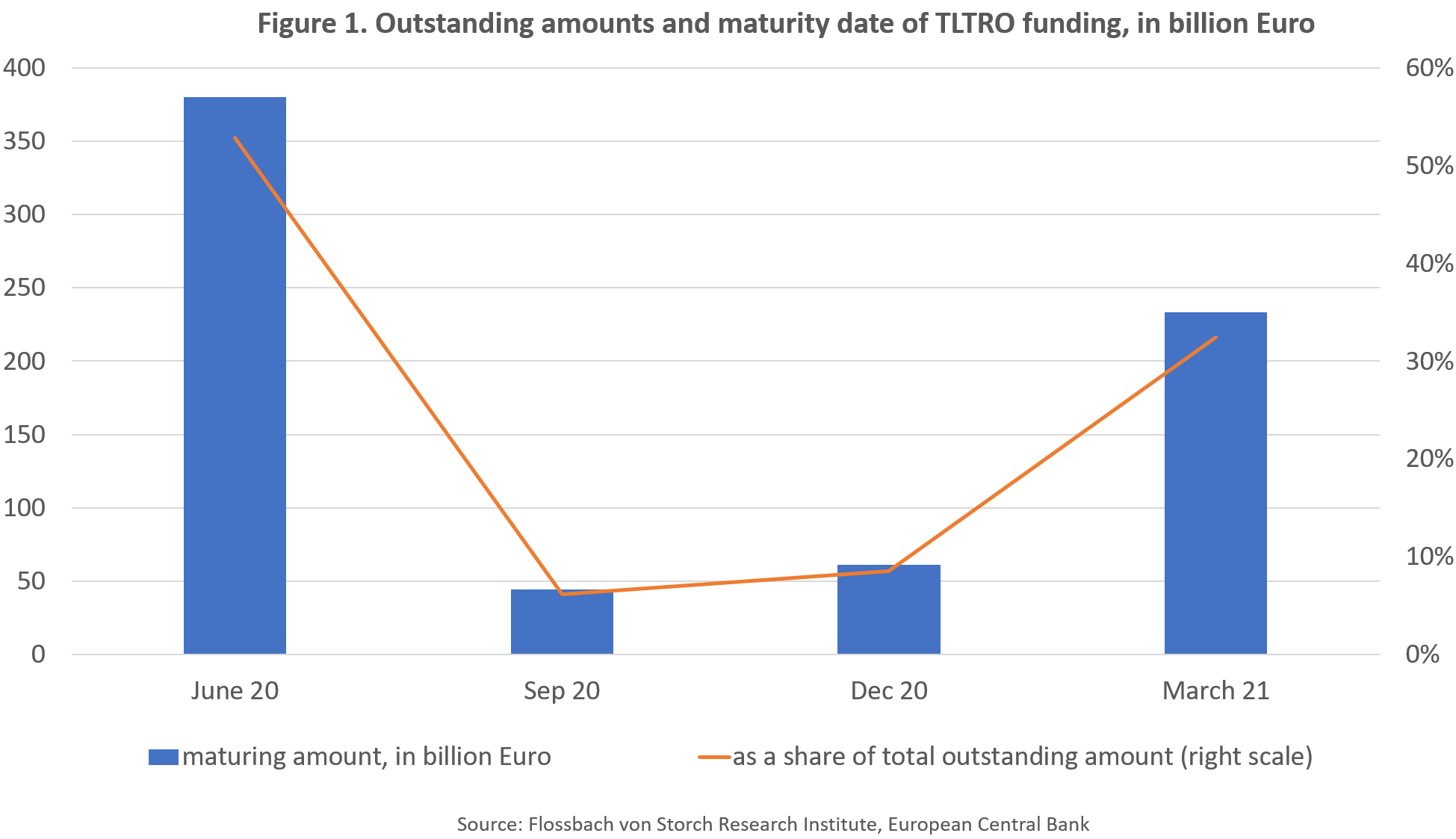

As a complement to the regular pre-crisis open market operations – main refinancing operations and three-month longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) – the ECB has launched several rounds of unconventional LTROs with more favorable financing conditions for banks. Three-year LTROs were launched in 2013 (and matured between January and February 2015). A first series of four-year TLTROs (targeted LTROs) was announced in June 2014 and a second series (TLTRO II) in March 2016. The currently outstanding amount is 719 billion Euro and will mature between June 2020 and March 2021 (Figure 1).

The idea behind TLTROs was to stimulate bank lending to the real economy and thus economic growth. This should be achieved through long-term funding at attractive conditions. In the first round of TLTROs, the amount that banks could borrow was tied to their loans to non-financial corporations and households. Under TLTROs II, the interest rate to be applied was linked to the participating banks’ lending patterns. The more loans granted to non-financial corporations and households (except for housing loans), the more attractive the interest rate was on the TLTROs II loans. The loan conditions under TLTROs II could be as low as the interest rate on the deposit facility, i.e. -0.4%.

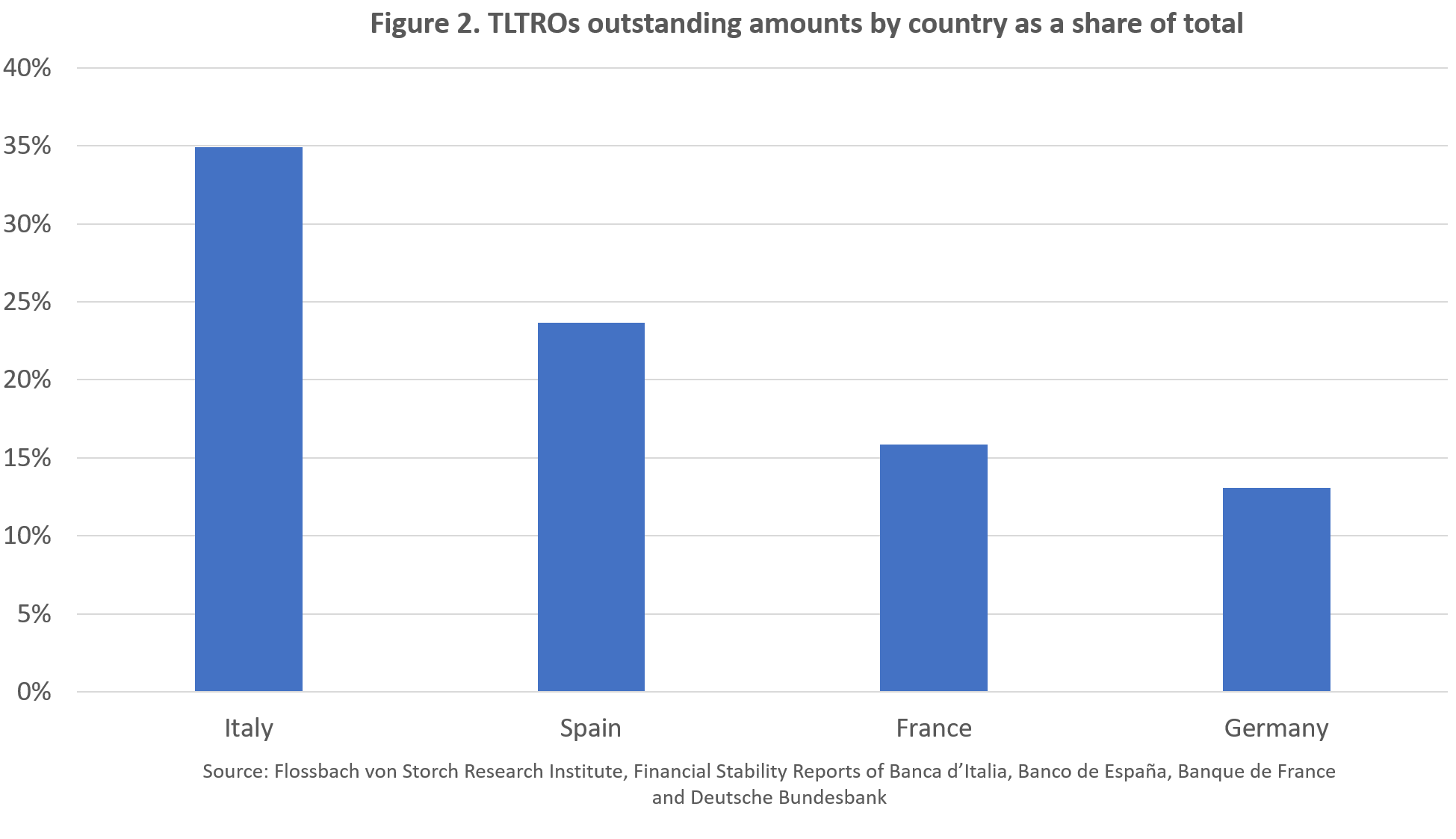

The popularity of TLTROs II has a clear southern bias. Of the total outstanding amount, almost 35% was used by Italian and 24% by Spanish banks. The remaining 16% and 13% were used, respectively, by French and German banks (Figure 2). The reason for this is that TLTROs in effect subsidize lending by weaker banks or banks in weaker economic environments. When banks extend credit they create deposits. And when customers move the deposits from weaker to stronger banks the weaker banks have to replace them by more expensive borrowing in the market. This forces them to increase their lending rates. TLTROs represent a much cheaper alternative. Thus, with TLTROs the ECB can subsidize lending rates by weaker banks or banks in weaker regions. The intensive use of TLTROs II in Italy and Spain is reflected in the large liabilities of the central banks of these countries within the Target2 interbank payment system (EUR 478 billion Euro for Italy and EUR 402 billion Euro for Spain in January 2019).

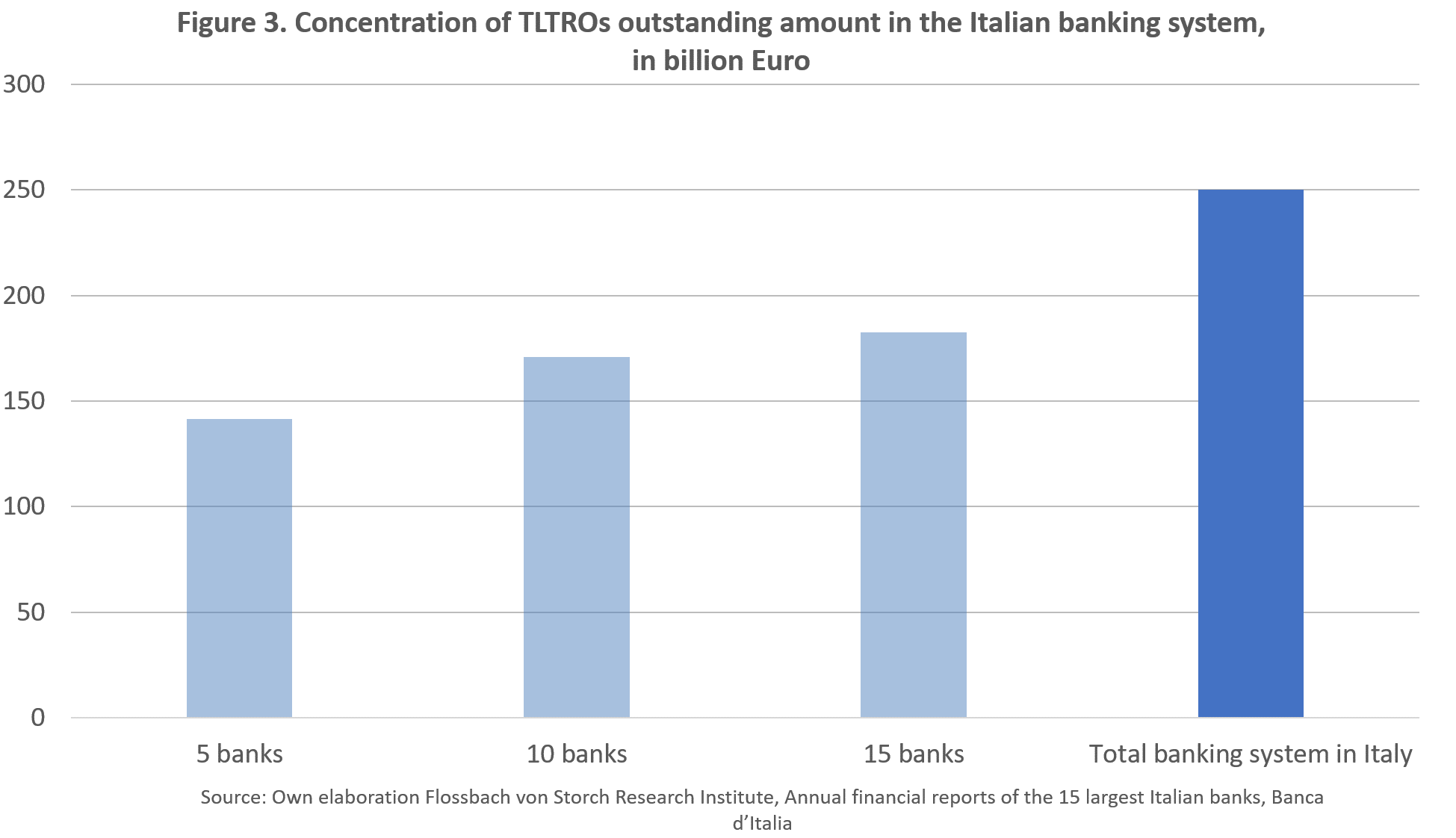

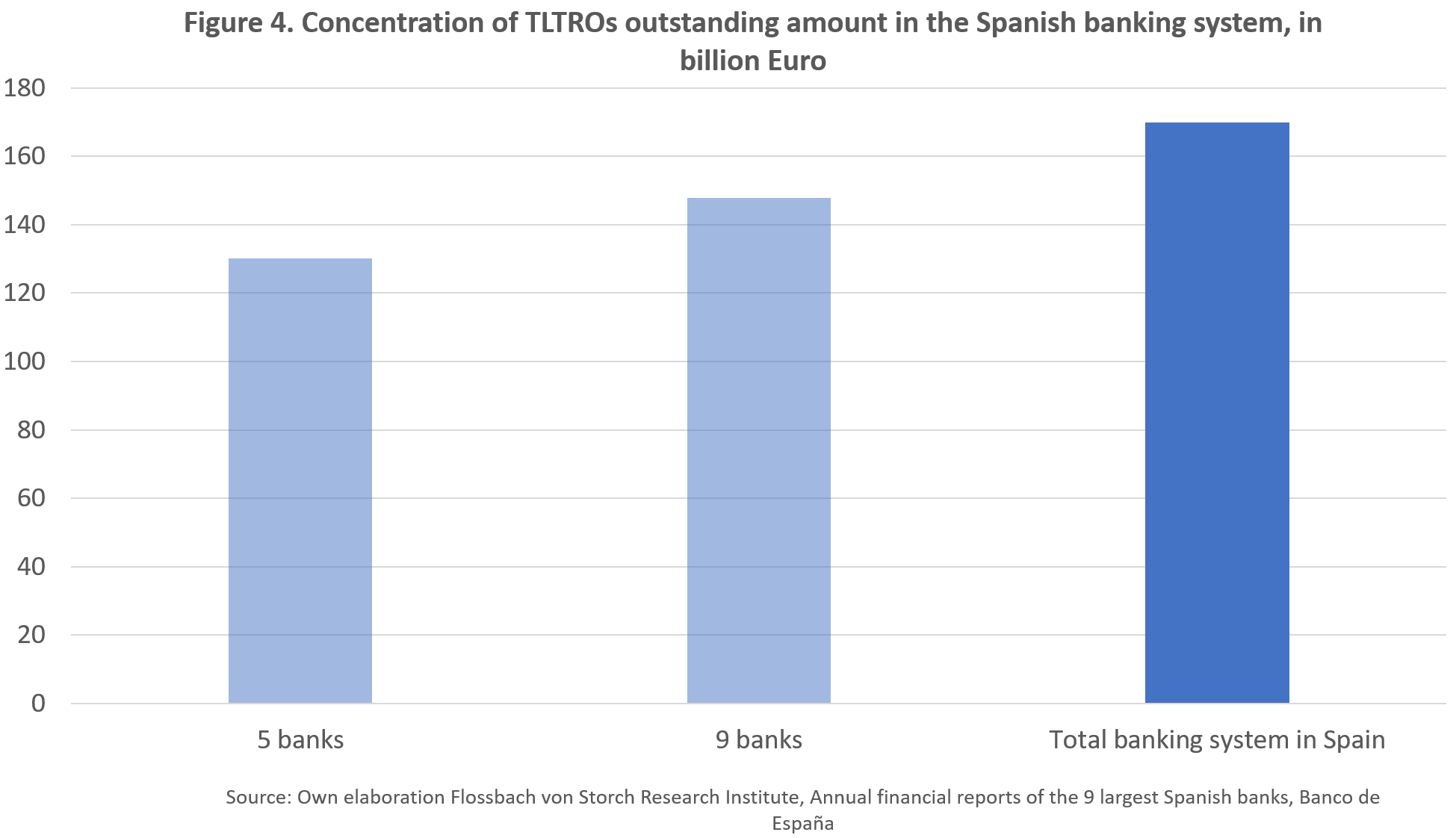

Moreover, there is a relatively high concentration of TLTROs in both the Italian and Spanish banking system. Of the total 250 billion Euro of TLTRO borrowing taken by Italian banks, almost 57% are held by five largest banks (Figure 3). In Spain, the concentration is even higher, as around 75% of TLTROs in the Spanish banking system are with five largest banks (Figure 4). This could lead the ECB to conclude that TLTROs are of systemic importance.

How not to throw out the baby with the bathwater?

In the current framework, TLTROs are subject to the paradox which forces the ECB to use an unconventional instrument even in good economic times. Only by relaunching (T)LTROs under conditions at least as good as under the current framework, the interest margins of banks – especially in Southern Europe (Italy and Spain) – would not be negatively affected and thus credit impulse would not be squeezed.

The current slowdown in economic activity and the core inflation rate of 0.96% moving away from the ECB’s goal should provide enough background for the ECB to justify a relaunch (T)LTROs. But this leaves the paradox alive in the future. To counteract this, the ECB may be inclined to introduce a more decisive innovation. Making TLTROs a permanent facility would indeed end the paradox, as the ECB would avoid having to justify the measure any more. To compensate the critics, the facility could have a shorter maturity than the current four years and be subject to a floating interest rate tracking the ECB’s main refinancing rate. This would leave the ECB at least a formal leeway, but would by no means imply an obligation to raise rates.

The time factor

Although the last tranche of TLTROs II will mature in March 2021, the details on the TLTRO-relaunch could already be announced at the next ECB meeting on 7th March or at latest in June. The reason for this is that under Basel III rules, funds with a maturity less than 12 months cannot be used to determine the so called net stable funding ratio (NSFR), which ensures that banks avoid excessive liquidity mismatches due to maturity transformation (lending long-term and funding themselves short-term).1 The NSFR requires banks to have enough funding with a residual maturity of more than one year. Since almost 380 billion Euro will mature in June 2020, it should be in the ECB’s interest to ensure funding continuity at favorable funding cost.

1 NSFR replaced at the end of 2016 the Structural Liquidity Ratio, which is calculated as the ratio between liabilities and assets with maturity above one year. Each bank sets the internal limit for this liquidity ratio. For instance, the Italian Unicredit sets the internal limit at 90%, meaning that at least 90% of the assets with a maturity above one year must be financed with liabilities with maturity above one year.

Legal notice

The information contained and opinions expressed in this document reflect the views of the author at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of the author. The opinions and expectations found in this document may differ from estimations found in other documents of Flossbach von Storch AG. The above information is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment advice or any other form of recommendation. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All authorial rights and other rights, titles and claims (including copyrights, brands, patents, intellectual property rights and other rights) to, for and from all the information in this publication are subject, without restriction, to the applicable provisions and property rights of the registered owners. You do not acquire any rights to the contents. Copyright for contents created and published by Flossbach von Storch AG remains solely with Flossbach von Storch AG. Such content may not be reproduced or used in full or in part without the written approval of Flossbach von Storch AG.

Reprinting or making the content publicly available – in particular by including it in third-party websites – together with reproduction on data storage devices of any kind requires the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch AG.

© 2024 Flossbach von Storch. All rights reserved.